Life and Society in the Colonial Carolinas

Southern colonies—especially the Carolinas—evolved through labor systems, land struggles, and cultural clashes.

The Dive

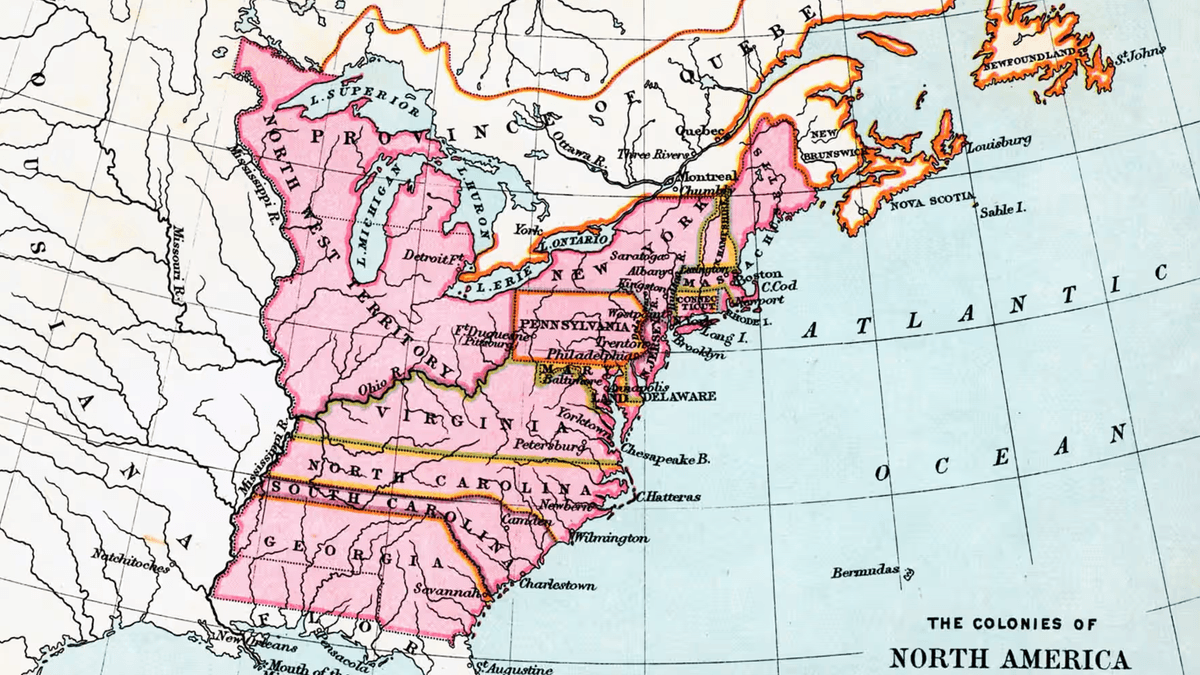

The story of the Carolinas is a tale of political favors, lofty visions, and hard realities. In 1663, King Charles II carved out a massive stretch of land between Virginia and Spanish Florida and gifted it to eight of his loyal supporters, the Lords Proprietors. These men were given near-feudal control over what would become Carolina, hoping to profit from settlement and trade. Their grand plan, with help from philosopher John Locke, envisioned a European-style aristocracy with titled nobility, huge estates, and a rigid social hierarchy. But this top-down system never stuck.

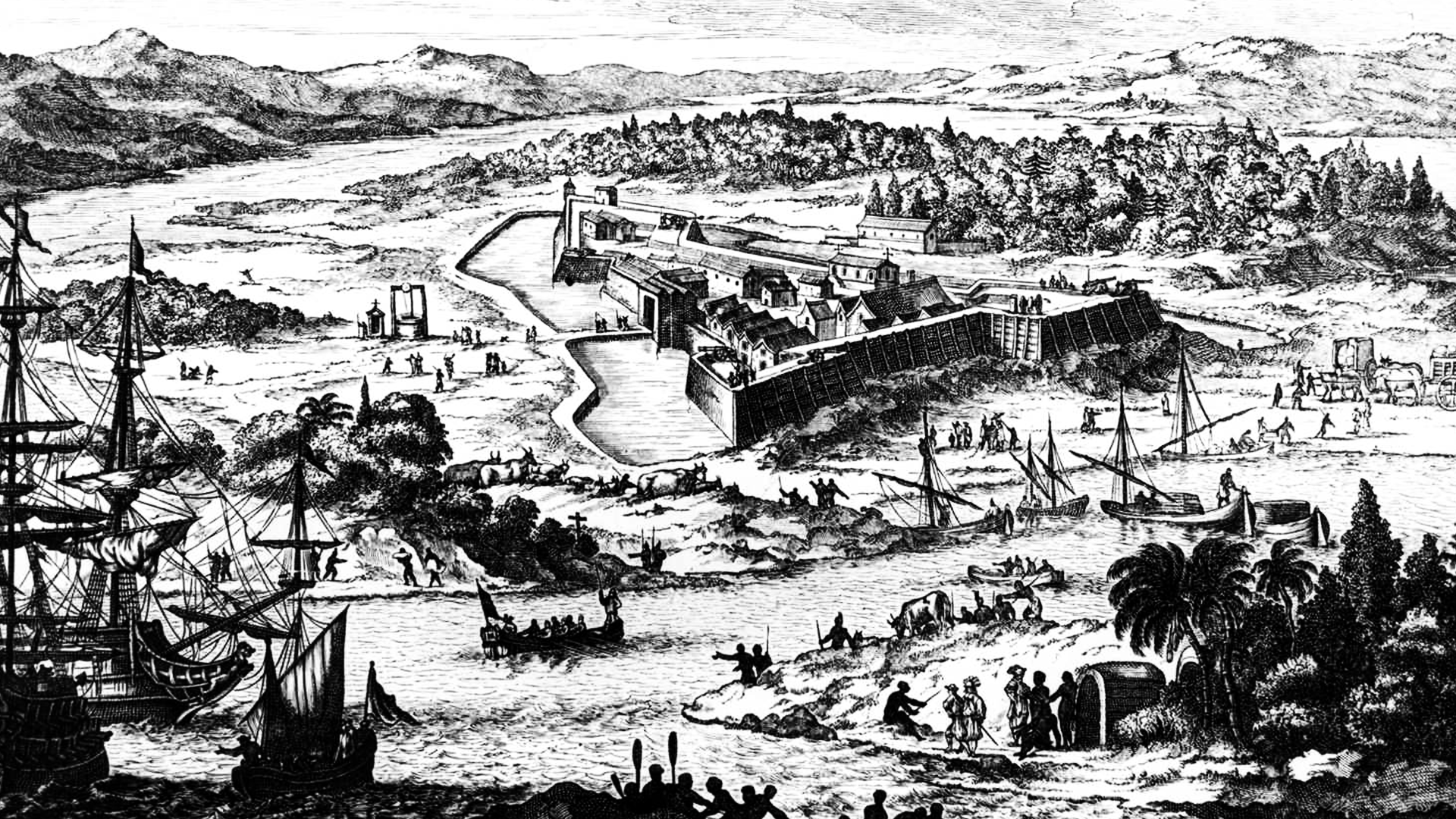

Carolina was too vast, too diverse, and too unruly. Settlers in the north, mostly small-scale farmers and former Virginians, resisted aristocratic control, while the southern region, centered around Charles Town (now Charleston), developed along different lines, thanks to its strong ties with the Caribbean and a booming slave-based plantation economy. The economic, geographic, and political differences between these regions were too great to manage under one government.

By 1712, the split was made official: North Carolina and South Carolina became two separate colonies. North Carolina remained more rural and decentralized, marked by independent farmers, maritime trade, and a rebellious streak that welcomed pirates. South Carolina, by contrast, transformed into a wealthy, slave-dominated society, growing rice and indigo for export and importing thousands of enslaved Africans to do the labor.

In North Carolina, Bath was the first incorporated town, a coastal hub for trade, politics, and pirates (hello, Blackbeard). But the colony’s real transformation came with the influx of settlers from Virginia, who brought with them two things: slavery and self-governance. That combo would define the Southern experience.

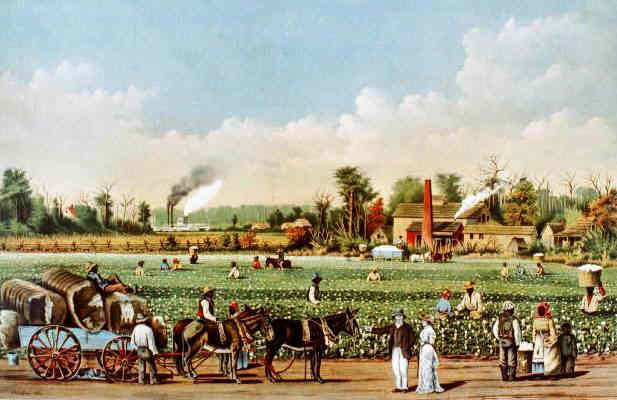

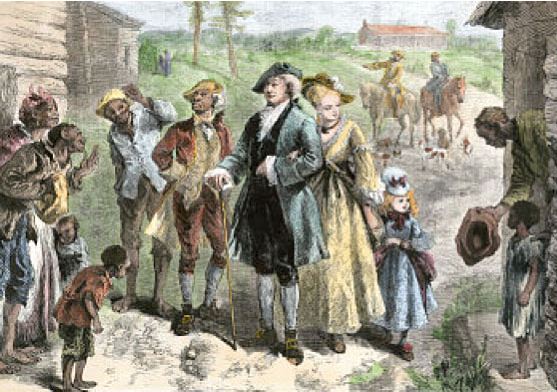

Class structure was clear and rigid: at the top, wealthy gentry who owned large plantations and enslaved dozens. Below them, small-scale yeoman farmers who worked their own land. Below them, indentured servants—mostly poor Europeans hoping to earn freedom through years of hard labor. And at the very bottom: enslaved Africans, whose labor fueled the colonial economy but whose lives were brutally dehumanized.

The key to wealth wasn’t talent or birth—it was land. Landowners held political power and defined social norms. Through systems like the 'headright system,' settlers could gain land just by paying for someone’s passage to the colonies. But with land came a problem: who would work it? Indentured servitude wasn’t enough. The answer? A brutal turn toward race-based slavery.

In South Carolina, settlers from Barbados imported African slaves familiar with rice cultivation. That expertise turned Carolina’s swampy lowlands into profitable rice plantations. By 1730, enslaved people outnumbered whites 2 to 1. The result? A Southern society that more closely resembled the Caribbean than Britain—economically powerful, socially unequal, and permanently reliant on slavery.

Resistance wasn’t absent. In North Carolina, the Tuscarora War (1711–1713) erupted when settlers encroached on Indigenous land and trafficked Native people into slavery. The Tuscarora destroyed New Bern, but were ultimately defeated and forced to migrate north, becoming the Sixth Nation of the Iroquois Confederacy. Indigenous resistance continued with the Yamassee War (1715), though it too ended in colonial victory and opened more land for white settlers.

Piracy thrived on the North Carolina coast, especially around Bath. Figures like Edward Teach (Blackbeard) made fortunes in smuggling and terrorizing ships, challenging colonial authority until the British Navy cracked down. Piracy may seem romanticized now, but in reality it was a symptom of a chaotic colonial world where law, trade, and power were still being figured out.

Meanwhile, life for average colonists (those without titles or estates) was harsh but not hopeless. Land was cheap and food was plentiful, especially meat and dairy. Colonists were often healthier and taller than their European counterparts. Yet, their voices remain mostly lost in history, as poor whites and enslaved people left behind few written records.

The Southern colonies weren’t just a footnote to Northern Puritanism. To understand America, we have to understand the Carolinas—both the promise and the price of their colonial experiment. They helped birth an economy based on exploitation, a culture of hierarchy, and a legacy of resistance, one that would reverberate long after independence was declared.

Why It Matters

Understanding life in the colonial South is crucial because it laid the groundwork for American social and economic systems that still influence us today. The power structures, racial hierarchies, and land-based wealth of this era set the stage for future conflicts, including the Civil War, and continue to shape the South's identity. It's not just about history, it's about unpacking the roots of inequality, resistance, and resilience that still echo in the modern world.

?

What made North Carolina and South Carolina develop differently despite starting as one colony?

How did the rise of plantation agriculture lead to the expansion of slavery in the South?

What were the causes and consequences of the Tuscarora War?

How did land ownership determine power and class in colonial society?

In what ways did piracy challenge colonial governments and economies?

Dig Deeper

An overview of early English colonization efforts including Jamestown, Massachusetts, and the Lost Colony at Roanoke.

Covers various colonies and discusses religious freedom, fair treatment of women and Indigenous peoples, and early Southern development.

Explores the political and historical reasons for the division of the Carolinas into two separate colonies.

Related

English Colonization: Roanoke, Jamestown, and Early Settlements

From vanished colonies and tobacco empires to pirates and indigenous resistance, the story of England’s first attempts at colonization in North America is anything but boring.

The 13 Colonies: Seeds of a New Nation

How did thirteen scattered colonies along the Atlantic coast grow into the foundation of a new nation?

The Market Revolution: How Innovation Transformed America

In the early 1800s, America changed from a land of small farms to a booming nation of factories, railroads, and markets. The Market Revolution connected people, goods, and ideas—while also revealing deep inequalities in who benefited from progress.

Further Reading

Stay curious!