The First Great Awakening: Faith, Fire, and a New American Identity

The First Great Awakening helped shape a more unified American identity and influenced the political mindset that led to the Revolution.

The Dive

In the early 1700s, many colonial churches had grown formal and detached. Religion had become something recited rather than felt, filled with rigid sermons, polished theology, and strict hierarchy. Ministers preached to the head, not the heart. But beneath this order, a new restlessness was stirring. Ordinary people—farmers, craftsmen, mothers, and servants—hungered for a more personal connection to faith. They wanted a religion that moved them, not just one that told them what to think.

At the same time, the Enlightenment was spreading across the Atlantic. Thinkers like John Locke and Isaac Newton emphasized science, logic, and human reason. Many colonists were drawn to these new ideas, which valued evidence over blind faith. Yet others responded in the opposite direction, launching a spiritual revolution that reignited emotion, experience, and the soul. The result was the First Great Awakening, a religious revival that swept through the colonies and forever changed the course of American culture.

The first sparks flew in the Middle Colonies. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, William Tennent, a passionate Presbyterian minister from Scotland, and his sons began holding revival meetings that emphasized personal salvation and heartfelt preaching. Their small training school for young ministers, nicknamed the “Log College,” became a symbol of this new religious energy and would later grow into Princeton University, a sign that faith and education could coexist in a changing world.

In New England, Jonathan Edwards became the face of the Awakening. A brilliant yet fiery theologian, Edwards blended intellect with emotion, urging listeners to seek a direct, personal relationship with God. His 1741 sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” used unforgettable imagery to warn of spiritual complacency, comparing humanity to a spider dangling by a thread over the fires of judgment. His message was not just fear, it was awakening. He wanted people to feel the urgency of grace and the possibility of change.

Then came the traveling preacher George Whitefield, whose booming voice and dramatic style made him a celebrity in the colonies. Between 1739 and 1741, he journeyed from Maine to Georgia, preaching in open fields to crowds of thousands. Whitefield’s performances were electrifying. He wept, shouted, and spoke in simple, emotional language that anyone could understand. His ally, John Wesley, would later found the Methodist Church, which grew rapidly in both England and America.

The Awakening was not just a religious event, it was a social earthquake. Old divisions quickly emerged. Traditional ministers, known as “Old Lights,” criticized the emotionalism of the movement and worried about chaos. The “New Lights,” however, believed that real faith came from within and that God’s truth was not limited to ordained ministers. Congregations split, new denominations arose, and people began choosing churches that matched their personal beliefs. This freedom of religious choice mirrored the growing desire for political freedom that would soon sweep the colonies.

In North Carolina, the Great Awakening struck at the very foundation of the Anglican Church, which had long been tied to colonial government and social order. Traveling preachers, especially Baptists and Methodists, spread their message through small towns and rural settlements, often meeting in homes or outdoor gatherings rather than official church buildings. The movement gave voice to poor farmers and outcasts who felt alienated by the formality of the Anglican elite. By the mid-1700s, Baptist and Methodist congregations were flourishing throughout the Carolinas, reshaping the region’s religious and cultural identity.

Revivals often took place outdoors, beyond the walls of traditional churches. Preachers spoke in fields, barns, and town squares, welcoming everyone who wished to listen. For the first time, women, enslaved Africans, free Black people, and Native Americans participated more fully in public religious life. Though the movement did not abolish inequality, it introduced the radical idea that every soul regardless of class, race, or gender had equal worth in the eyes of God.

The Awakening also sparked an explosion of learning. Preachers urged people to read the Bible themselves, and literacy spread quickly. Schools and colleges sprang up to train ministers who could balance passion with education, institutions like Princeton, Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth all trace part of their origin to this revivalist wave. In these classrooms, future leaders learned not only theology but also the art of independent thought.

By the 1750s, the Great Awakening had reached the Southern backcountry, carried by Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist missionaries. In small communities far from coastal cities, revival meetings offered a rare sense of equality and belonging. Choosing pastors, organizing congregations, and debating faith gave ordinary colonists practice in self-government, long before it became a political reality.

The First Great Awakening was, at its core, a movement of the people. It taught colonists to question authority, trust their conscience, and believe that moral truth could come from within, not just from kings, bishops, or hierarchies. Though its message began in the pulpit, its spirit echoed far beyond it. By uniting the colonies through shared emotion and common purpose, the Awakening helped forge the earliest sense of an American identity—a belief that individuals had both the right and the responsibility to think, speak, and act for themselves.

Why It Matters

The First Great Awakening didn’t just set church pulpits on fire, it lit the fuse of American independence. By teaching people that they could seek truth for themselves, it laid the groundwork for a culture that would soon demand liberty, self-rule, and justice from its leaders.

?

How did the First Great Awakening challenge traditional religious authority?

What connections can you draw between the revival movement and the American Revolution?

Why did emotional and personal preaching appeal to so many colonists during the time of the Great Awakening?

How did the Great Awakening shape American views on democracy, education, and freedom?

Dig Deeper

The Great Awakening breaks out in America when several new religious leaders such as George Whitefield emerge to revive the church. This brings about new ways of worshipping and ultimately new religious sects such as Baptists and Presbyterians.

Related

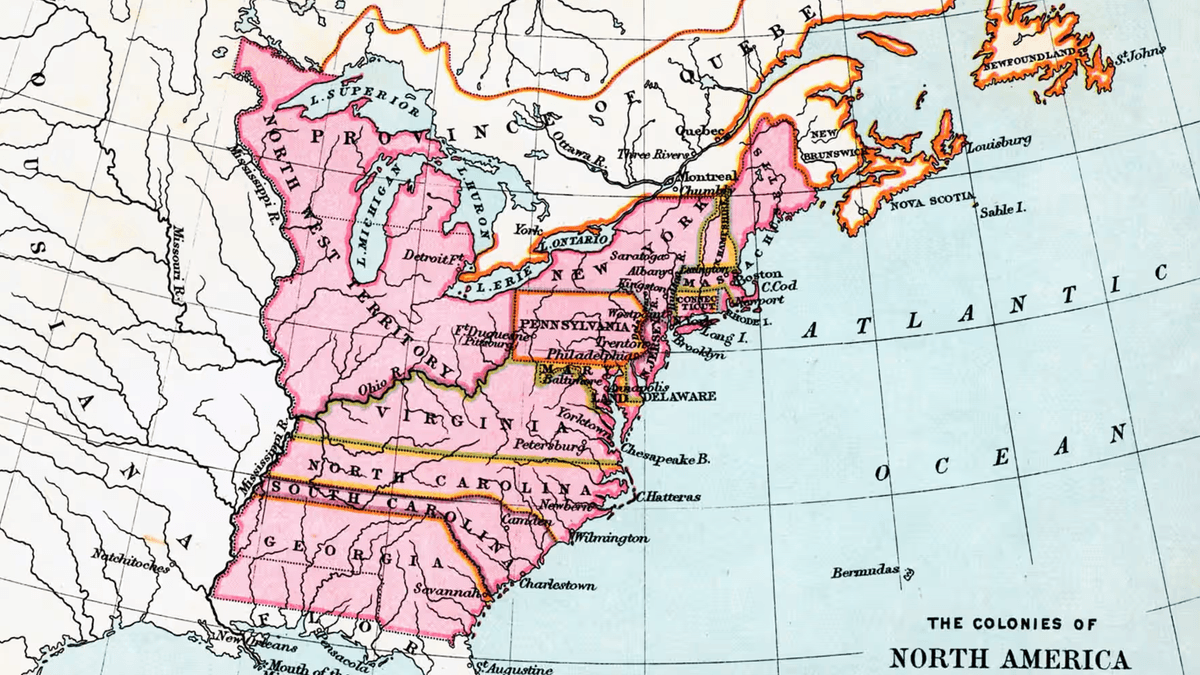

The 13 Colonies: Seeds of a New Nation

How did thirteen scattered colonies along the Atlantic coast grow into the foundation of a new nation?

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Indigenous Roots of American Democracy

Long before the Founding Fathers gathered in Philadelphia, a league of Native Nations had already established one of the world’s oldest participatory democracies—an Indigenous blueprint for unity, peace, and governance.

Life and Society in the Colonial Carolinas

Explore the rise of plantation agriculture, slavery, class divisions, and the shaping of daily life in the colonial South—particularly in North Carolina and South Carolina.

Further Reading

Stay curious!