Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch was born in Germany in 1889, at a time when girls were expected to grow up, get married, and not make much noise in the world. But Hannah was different. Even though she had to leave school at 15 to care for her sister, she never let go of her love for creating. When she was older, she studied design in Berlin, where she learned how to work with shapes, patterns, and printed images. This training helped her develop a sharp eye for detail. She eventually changed her name from Anna to Hannah.

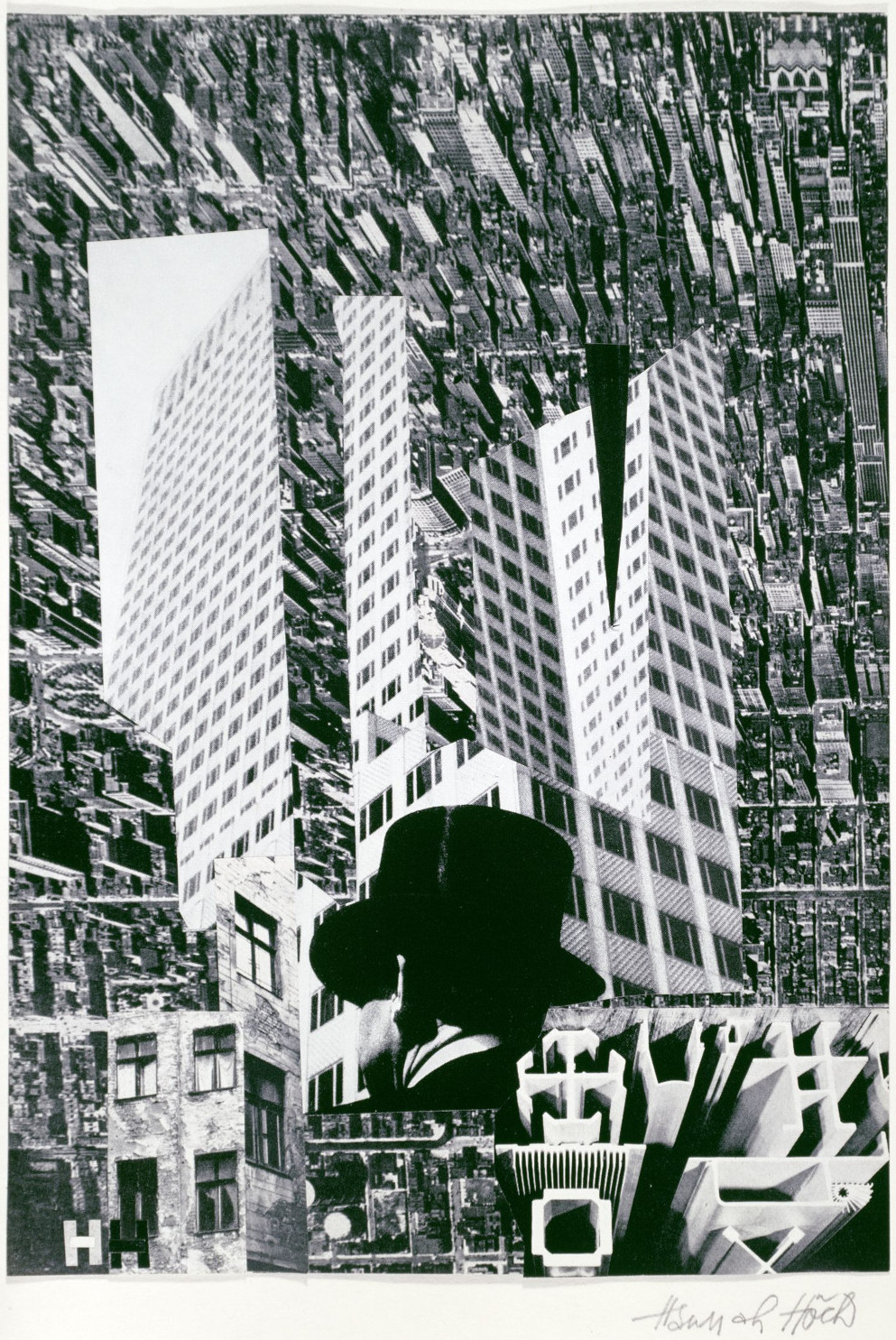

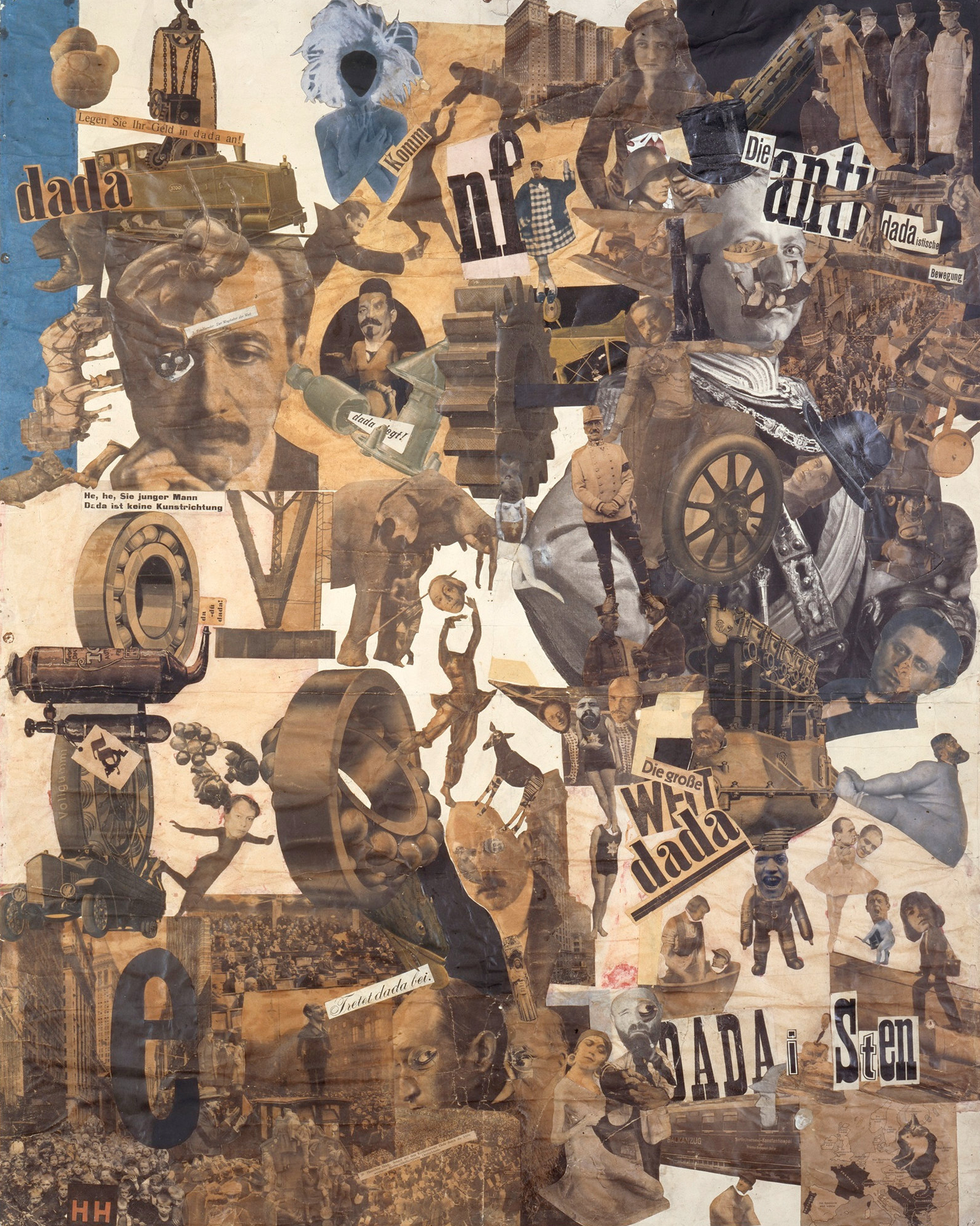

Hannah became a major figure in the Dada movement, a group of artists who believed that the world after World War I was so confusing and unfair that art needed to break rules and challenge people’s ideas. Even though the Dada group was full of men who did not always treat her as an equal, Hannah invented something that none of them had done before: photomontage. This art form involved cutting photographs from magazines, newspapers, and advertisements, then rearranging them into surprising or strange combinations. Hannah used this technique to question how society viewed women, to point out political hypocrisy, and to show how everyday images could be turned into powerful messages. Her 1919 masterpiece, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic, used humor, sharp criticism, and bold design to challenge the political leaders of her time.

Hannah’s contributions were groundbreaking because she showed the world that art didn’t need fancy paint or perfect lines to make a strong point. She believed that anything—photographs, letters, scraps of paper—could be used to communicate big ideas. Her style was bold, layered, and unpredictable. She mixed faces, bodies, machines, animals, and objects to create dreamlike scenes that made people rethink familiar things. She explored themes like the “New Woman,” a modern woman with independence and ambition, and she brought attention to unfair expectations placed on women.

Even when the Nazis banned her work and called it “degenerate,” Hannah kept making art in secret, protecting her pieces by hiding them away so they wouldn’t be destroyed. After World War II, she continued experimenting, creating abstract works full of movement and energy. By the 1960s and 70s, museums finally began to recognize her talent, and she became known worldwide as a pioneer of modern art and a foundational figure in feminist art history. Today, Hannah Höch is celebrated for her courage, her creativity, and her belief that art can push boundaries, challenge unfair systems, and help people see the world in new ways. Her photomontages opened doors for future artists in Surrealism, Pop Art, Punk, and Postmodernism, proving that even tiny scraps of paper can change the story of art forever.

?

How did Hannah Höch’s identity as a woman and queer artist shape her role in the Dada movement?

What is photomontage, and why was it so powerful in critiquing media and politics?

How does Höch’s work challenge traditional ideas of beauty and gender roles?

Why did the Dada movement emerge after World War I, and how was Höch’s work different from her male peers?

In what ways does her work connect to modern feminist and LGBTQ+ art?

Why do you think her name is less well known than some of her contemporaries, and how can that change?

What does it mean to be a revolutionary artist, and how did Hannah Höch embody that?

Dig Deeper

Explore Hannah Höch’s life, her revolutionary use of photomontage, and how she helped redefine modern art and feminist aesthetics.

In this video, you'll find out the answers to these questions and learn more about the famous art movement called DADAISM.

Discover more

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger’s work is a masterclass in speaking truth to power. She uses the tools of mass media not to sell, but to subvert, to interrupt the daily scroll of consumption with urgent, unforgettable questions. Her white-on-red commands force us to confront the systems we’re often too busy to question: capitalism, patriarchy, surveillance, conformity. Her work isn’t quiet, it’s confrontational. And that’s the point. In a world of endless noise, Kruger reminds us that boldness still breaks through.

Pablo Picasso

Picasso showed us that art isn’t just decoration, it’s a language. One that speaks in shapes, colors, and symbols. He dared to make things ugly, strange, or uncomfortable if it meant telling the truth. That’s the kind of bold creativity that still inspires artists today.

Faith Ringgold

Faith Ringgold didn’t just make art—she quilted justice, memory, and revolution into every thread. Her work teaches us that stories passed down become power passed forward, and that when we tell the truth in color, in fabric, in fearless honesty, we don’t just preserve history, we transform it. The future is stitched by those brave enough to remember and reimagine.

Further Reading

Stay curious!