Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced relocation of Native American tribes from the southeastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi.

The Dive

By the 1830s, the United States was a young and ambitious nation, restless for expansion. Land was seen as wealth, power, and promise. White settlers, politicians, and land speculators looked south and west and saw fertile soil, timber, and, after 1830, even gold gleaming in Cherokee territory. The hunger for land was so strong that it overpowered both morality and law. In that same year, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, a law that gave the federal government the authority to pressure or force Native American nations to give up their ancestral homelands and move west of the Mississippi River. It was promoted as “voluntary relocation.” In truth, it was ethnic cleansing written into law.

For generations, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations had lived across the southeastern United States. They were skilled farmers, traders, and diplomats. Over time, they adapted many aspects of European-American culture, adopting literacy, Christianity, written laws, and even plantation-style farming. Sequoyah’s creation of a written Cherokee language in 1821 brought literacy to thousands, and the Cherokee Constitution of 1827 established a representative government. White Americans called them the “Five Civilized Tribes,” believing that assimilation would earn them security. But assimilation did not protect them from greed.

In 1830, gold was discovered on Cherokee land, sparking a rush of prospectors. Georgia passed laws that stripped the Cherokee of their rights, banned their tribal government, and divided their lands into plots to be given away to white citizens through lotteries. When the Cherokee Nation took their case to the Supreme Court in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Court ruled in their favor, declaring that Georgia had no authority over Cherokee lands. It was a victory in principle—but one that meant little in practice. President Andrew Jackson, a fierce advocate of removal, reportedly responded to the decision with chilling defiance: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.”

In 1835, a small, unauthorized group of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, agreeing to exchange their lands east of the Mississippi for $5 million and territory in what is now Oklahoma. This treaty was not approved by the Cherokee government or its people. Over 15,000 Cherokees, led by Principal Chief John Ross, petitioned Congress to reject it. Their protests were ignored. The Senate ratified the treaty by a single vote, sealing the fate of the Cherokee Nation.

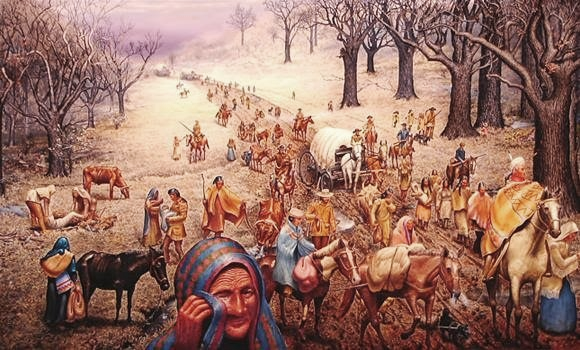

In May 1838, federal troops and state militias began the forced removal. Families were herded at gunpoint into crowded stockades with little food or sanitation. Homes were looted. Parents were separated from their children. In the fall and winter, approximately 16,000 Cherokee were marched 800 miles west. They traveled through freezing rain, snow, and mud, often without adequate clothing, shoes, or shelter. Disease spread quickly through the camps. Dysentery, pneumonia, and starvation claimed lives daily. Missionary doctor Elizur Butler, who accompanied them, estimated that more than 4,000 Cherokee—nearly a fifth of the population—died along the way.

Survivor accounts describe scenes of unimaginable loss. One recalled, “Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave Old Nation. Women cry and make sad wails. Children cry and many men cry… but they say nothing and just put heads down and keep on go towards West.” For those who lived through it, the Trail of Tears was not a single path but many overlapping routes of suffering that stretched across Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas into Indian Territory.

The Cherokee were not alone. Between 1830 and 1850, around 100,000 Native Americans from numerous tribes were forced westward. The Choctaw were the first, losing thousands to disease and exposure. The Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole followed, some transported in chains, others dying by the roadside. Even those who resisted militarily—like the Seminoles in Florida—eventually faced defeat, imprisonment, or exile.

Yet even in the face of this brutality, Native nations endured. The Cherokee rebuilt their government in Indian Territory, establishing a new capital at Tahlequah, Oklahoma. They reopened schools, rebuilt farms, and continued their newspaper, The Cherokee Advocate. A small group who had evaded removal remained in the mountains of North Carolina, forming what is now the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians—a living reminder of resilience in the face of injustice.

The Trail of Tears stands as one of the most devastating episodes in U.S. history, not only for its human cost but for what it revealed about national priorities. The same government that celebrated liberty and democracy also authorized mass displacement and death. The Indian Removal Act was not an isolated event; it was part of a broader pattern of expansion that placed land above life. It set a precedent for future policies of forced assimilation, broken treaties, and cultural erasure.

Why It Matters

The Trail of Tears is a stark example of how U.S. government policies, driven by expansionist ambitions and economic interests, can strip away the rights, land, and dignity of entire communities. It exposes the deep contradictions between America’s stated ideals of liberty and justice and its actions when political gain outweighs human rights. For the Cherokee and other tribes, it was both a profound tragedy and a testament to resilience, as survivors rebuilt their communities, governments, and cultures despite immense trauma. Studying this history challenges us to confront the long-term consequences of injustice, to critically examine the balance between national growth and human rights, and to uphold the principles of sovereignty and human dignity for all peoples.

?

How did the discovery of gold on Cherokee land accelerate their removal?

Why did the Supreme Court's decision in Worcester v. Georgia fail to protect Cherokee sovereignty?

How did the Treaty of New Echota contribute to divisions within the Cherokee Nation?

What does the Trail of Tears reveal about U.S. expansionist policies in the 19th century?

How have the Cherokee Nation and Eastern Band of Cherokee preserved their culture despite removal?

Dig Deeper

A concise overview of the forced displacement of Native American tribes in the 1830s, including the hardships and deaths along the Trail of Tears.

A critical look at Andrew Jackson’s legacy, including his role in the Indian Removal Act and its consequences.

Related

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Indigenous Roots of American Democracy

Long before the Founding Fathers gathered in Philadelphia, a league of Native Nations had already established one of the world’s oldest participatory democracies—an Indigenous blueprint for unity, peace, and governance.

The Cape Fear & Waccamaw Siouan: Indigenous History of Southeast North Carolina

Long before the first European ships arrived at the Carolina coast, the Cape Fear River and Lake Waccamaw were home to thriving Indigenous communities.

Westward Expansion, Sectionalism, and the Road to Civil War

Manifest Destiny fueled territorial growth, but it also deepened sectional divides—turning political disagreements over slavery and states’ rights into irreconcilable conflicts that led to civil war.

Further Reading

Stay curious!