U.S. Imperialism: The Spanish-American War and Its Aftermath

The Dive

The Spanish-American War began in April 1898 in the context of Cuba’s long struggle for independence from Spain. Spanish efforts to suppress Cuban rebels included harsh policies that caused widespread suffering, which were heavily reported in American newspapers. Sensational journalism—often called yellow journalism—helped stir public sympathy for Cuban independence. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor in February 1898, killing 266 American sailors, public pressure for war intensified, even though the exact cause of the explosion was never definitively proven at the time.

Congress declared that Cuba had a right to independence and authorized military force against Spain, while officially renouncing any intention to annex Cuba. The war itself was brief and overwhelmingly one-sided. American naval victories in Manila Bay in the Philippines and near Santiago, Cuba, quickly destroyed Spanish fleets. By August 1898, Spain had effectively surrendered. Although the war lasted only four months, its consequences reshaped the United States’ role in the world.

The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, formally ended the war. Spain relinquished control of Cuba and ceded Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States. The United States also purchased the Philippines for $20 million. This marked a major shift: for the first time, the United States controlled overseas territories far from the North American mainland, territories that were not intended to become states. The nation that had once defined itself through anti-colonial revolution was now governing colonies abroad.

Cuba was granted formal independence, but its sovereignty was limited by the Platt Amendment, which the United States required Cuba to include in its constitution. The amendment gave the United States the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and secured a permanent naval base at Guantanamo Bay. Although the United States didn't annex Cuba, it maintained significant influence over Cuban political and financial decisions, shaping the island’s development for decades.

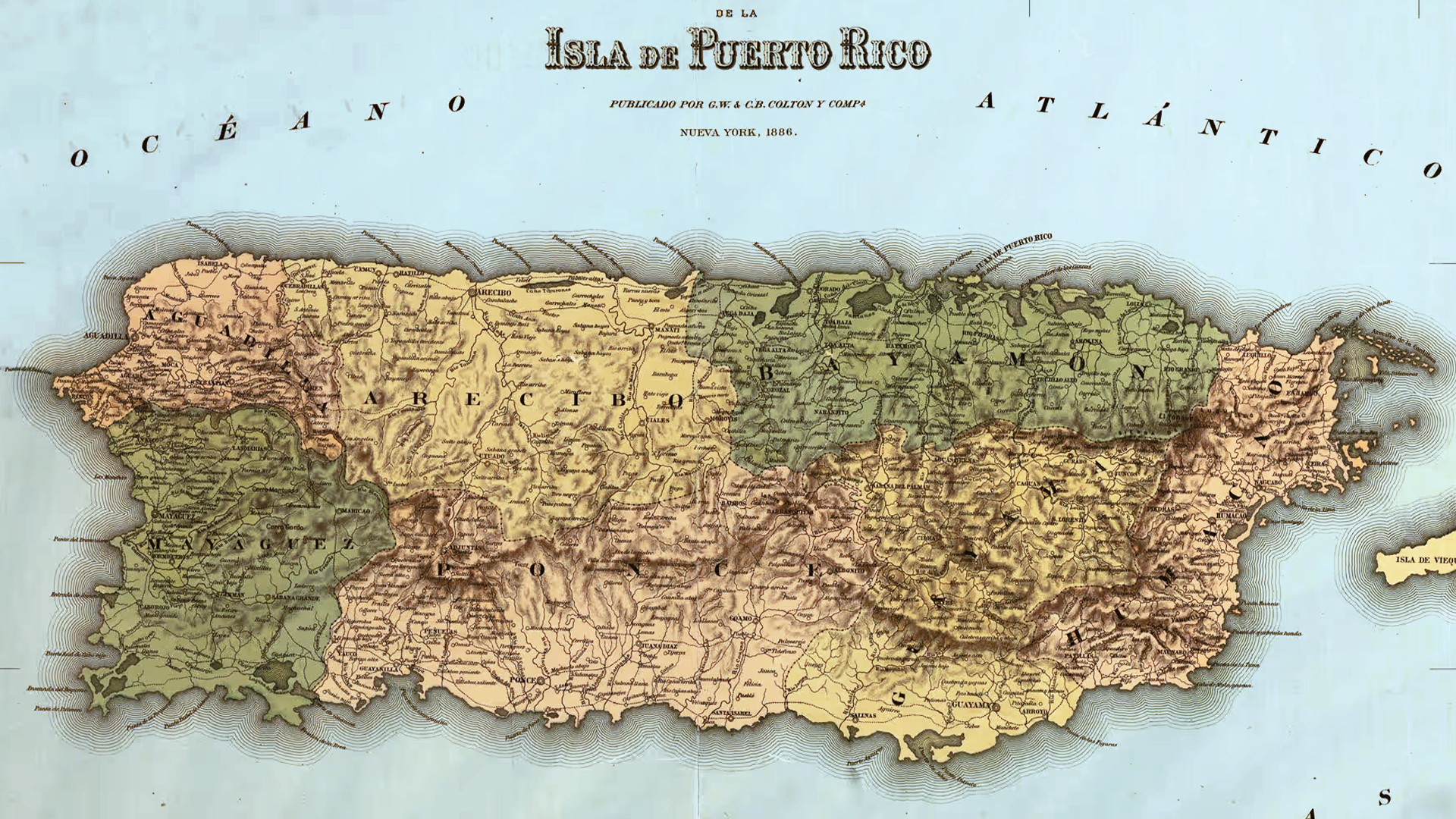

Puerto Rico became an unincorporated U.S. territory under the Foraker Act of 1900. The Supreme Court’s Insular Cases (beginning in 1901) established that full constitutional rights did not automatically extend to all territories. In 1917, the Jones-Shafroth Act granted U.S. citizenship to most Puerto Ricans, yet residents of the island still cannot vote for president and lack voting representation in Congress. These arrangements created an ongoing debate about territorial status, citizenship, and self-determination that continues today.

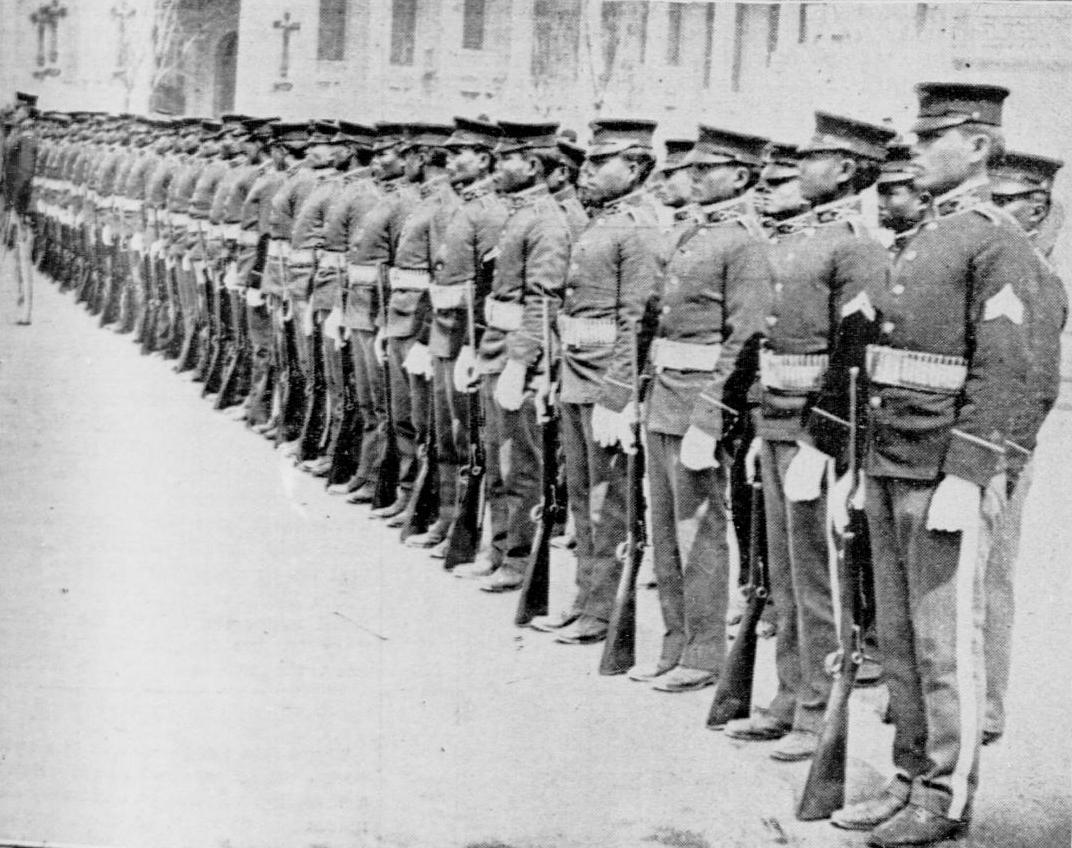

The Philippines experienced the most violent aftermath. Filipino revolutionaries led by Emilio Aguinaldo had declared independence from Spain and initially cooperated with American forces. However, when it became clear that the United States intended to retain control, conflict erupted. The Philippine-American War (1899–1902) involved guerrilla warfare and harsh counterinsurgency tactics. Tens of thousands of Filipino fighters and civilians died, and the war revealed the costs of imperial expansion. Although the United States described its policy as 'benevolent assimilation,' many Filipinos viewed it as foreign occupation.

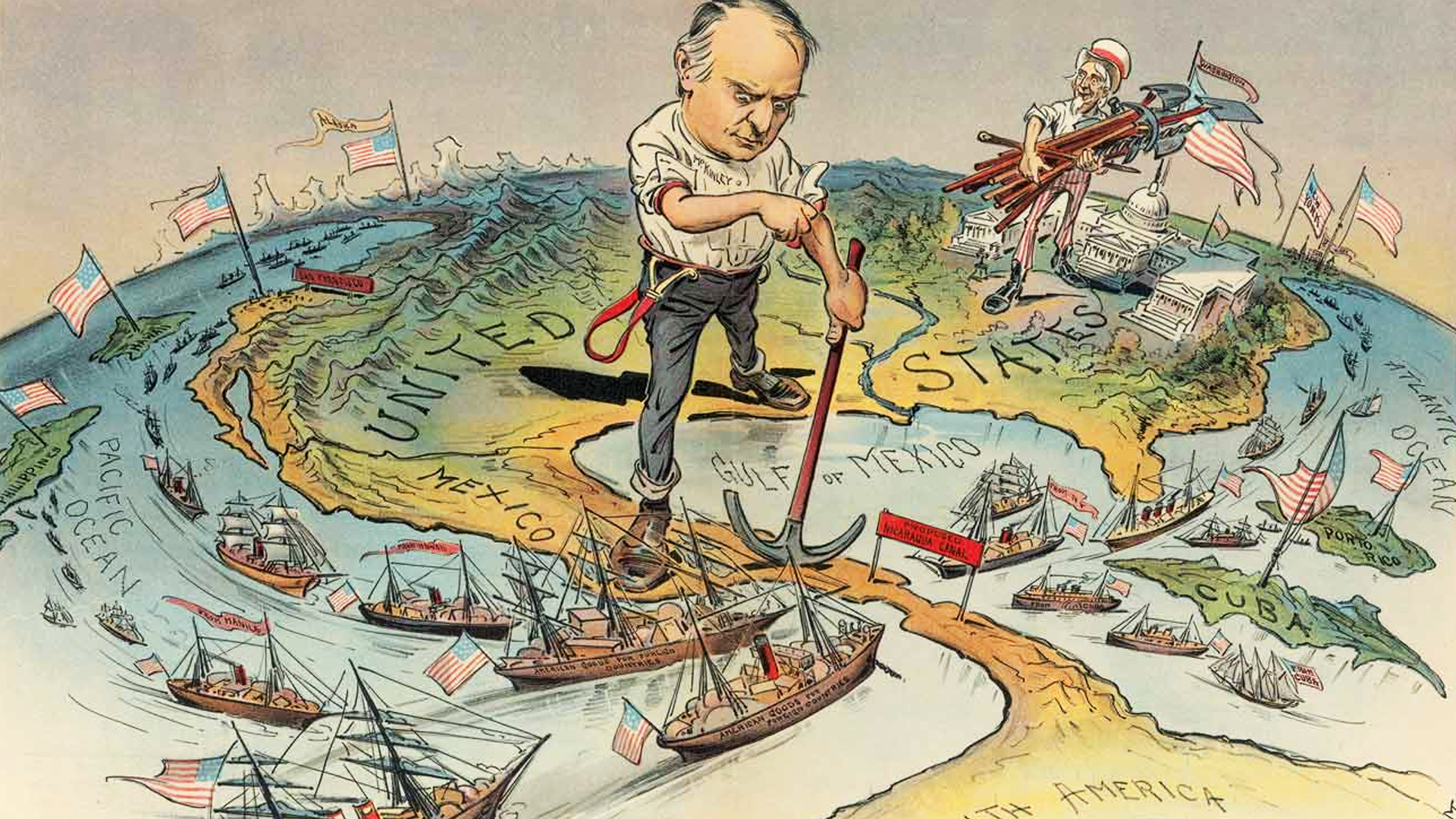

Imperial expansion sparked intense debate within the United States. Supporters argued that overseas territories would provide access to new markets, especially in Asia, strengthen naval power, and elevate America’s global standing. Opponents, including figures such as Mark Twain and members of the American Anti-Imperialist League, argued that ruling other peoples without their consent contradicted the Declaration of Independence and the principle that governments derive their powers from the governed. This debate raised enduring questions about democracy, race, and national identity.

The annexation of Hawaii in 1898 further demonstrated America’s turn toward overseas expansion. Taken together, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines signaled that the United States had joined European powers in pursuing global influence. This transformation positioned the nation as a major participant in international politics and set the stage for its growing involvement in world affairs throughout the twentieth century.

The long-term consequences of U.S. imperialism continued well beyond 1898. The Philippines were placed on a path to independence under the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 and achieved full independence in 1946 after World War II. However, U.S. military bases and strategic influence remained significant during the Cold War. Puerto Rico’s commonwealth status, established in 1952, continues to generate debate over statehood, independence, and territorial rights. The Spanish-American War thus marked a pivotal moment when the United States shifted from continental expansion to global power, confronting tensions between democratic ideals and imperial practice that remain historically significant.

Why It Matters

The aftermath of the Spanish-American War forced the United States to confront a contradiction at the heart of its identity: could a nation founded on anti-colonial revolution justify ruling other peoples without their consent? The debates over empire, citizenship, race, labor, and global power that began in 1898 continue to shape American foreign policy and domestic politics. Understanding this moment helps explain how the United States became a global power—and why questions about democracy and self-determination still matter.

?

How did the Treaty of Paris transform the United States into a global power?

Why did some Americans argue that imperialism violated the Declaration of Independence?

How did the Platt Amendment limit Cuban sovereignty?

What were the long-term consequences of U.S. rule in the Philippines?

Why does Puerto Rico’s territorial status remain controversial today?

Dig Deeper

An overview of how the United States acquired overseas territories at the turn of the twentieth century.

An explanation of the legal and political status of U.S. territories.

Related

The Encomienda System: Empire, Labor, and the Roots of Colonial Slavery

The encomienda system promised 'protection' and Christianization. What it delivered was forced labor, cultural erasure, and the blueprint for slavery in the Americas.

The U.S.-Mexico War

On May 13, 1846, the U.S. Congress declared war on Mexico. Behind the scenes? Land lust, slave politics, and a president with a map in one hand and a match in the other.

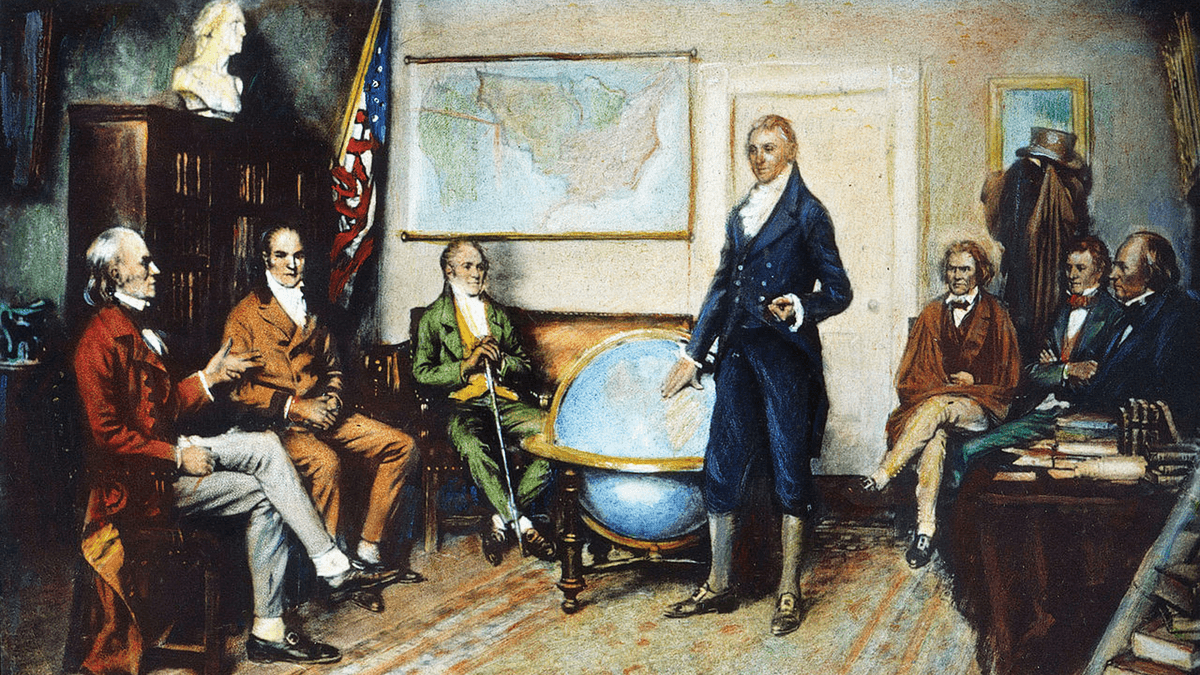

The Monroe Doctrine

How a young United States told the world to stay out of the Western Hemisphere—and what that meant for the Americas.

Further Reading

Stay curious!