Penicillin’s Serendipitous Discovery

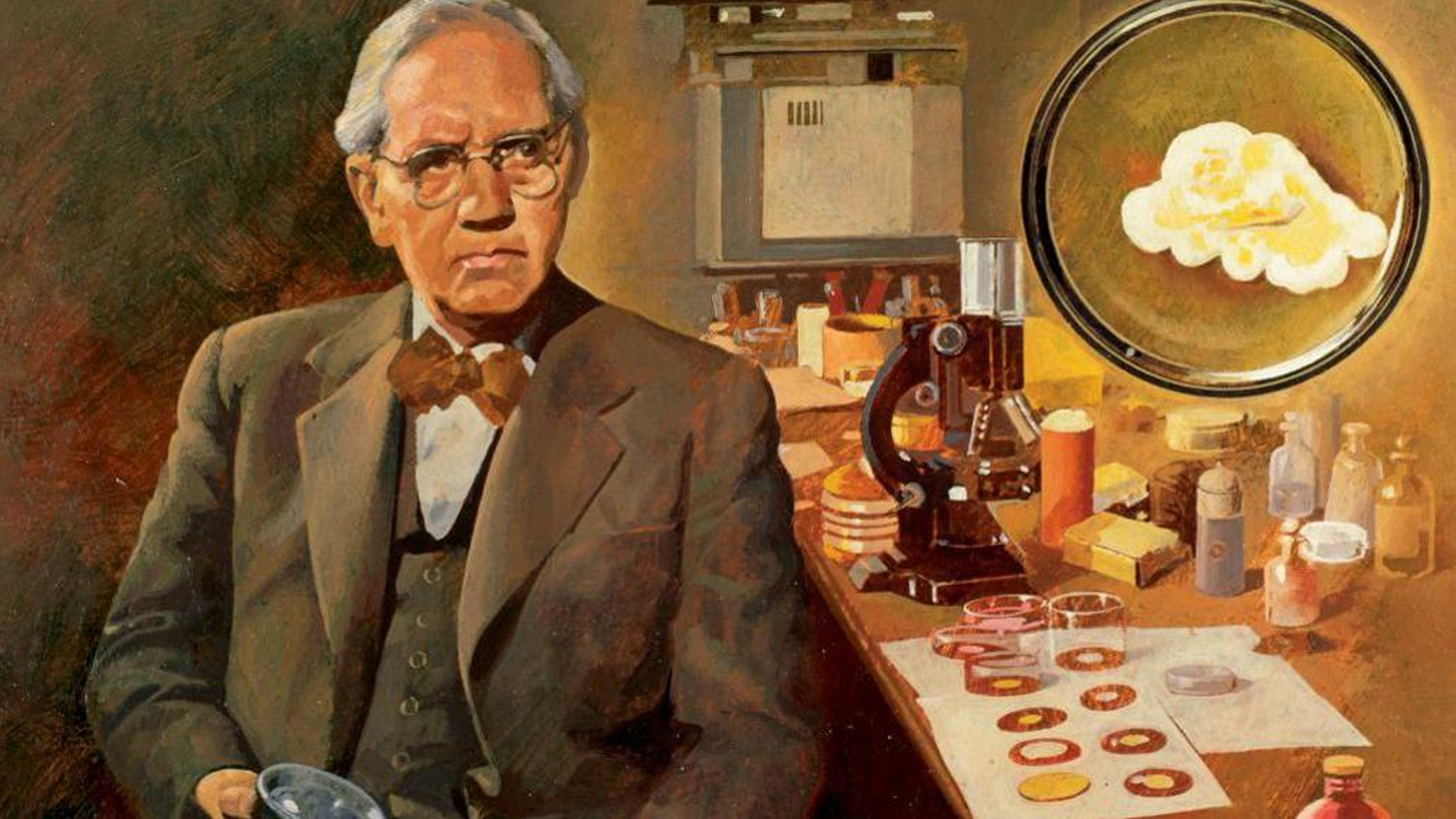

Alexander Fleming and a Petri dish showing a clear ring where Penicillium mold inhibits bacterial growth.

What Happened?

On September 3, 1928, Alexander Fleming noticed something unusual in his laboratory at St. Mary’s Hospital in London. Returning from holiday, he found that a Petri dish of staphylococcus bacteria had been contaminated by mold, but instead of ruining the experiment, the mold created a bacteria-free zone. Fleming realized that the mold was releasing a substance capable of killing harmful microbes.

The mold was identified as 'Penicillium notatum', and Fleming named its by-product penicillin. This was the first step toward the creation of antibiotics (medicines that fight bacterial infections). Although Fleming’s team could only produce small, unstable samples, the observation marked a breakthrough in medical science.

Before penicillin, bacterial infections such as pneumonia, scarlet fever, and sepsis often proved fatal. Doctors had no reliable way to treat even small wounds once they became infected. Fleming’s discovery offered the possibility that infections could be cured rather than simply endured.

The principle behind penicillin is called 'antibiotic action'. Certain molds and bacteria naturally produce chemicals to defend themselves against competing microbes. Fleming’s insight wasn't just that the mold killed bacteria, but that humans could harness this natural process as medicine.

Despite the importance of his finding, Fleming initially believed penicillin would mainly be useful in laboratories for separating bacterial strains. The challenge of purifying and producing the substance on a large scale proved too great for him and his assistants at the time.

It took another decade, and the efforts of scientists like Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, and Norman Heatley at Oxford University, to refine penicillin into a stable, usable drug. During World War II, their work—combined with mass production by U.S. pharmaceutical companies—turned penicillin into a life-saving treatment for soldiers and civilians alike.

The discovery of penicillin ushered in the antibiotic age, fundamentally changing medicine. It demonstrated the value of observation, persistence, and collaboration in science, and it reminds us how a single accident, if noticed and understood, can alter the course of human history.

Why It Matters

Penicillin turned once-deadly infections into treatable conditions and rewrote the social contract of medicine: a cut no longer meant a coin toss with sepsis. Fleming’s work shows how chance and curiosity intersect. The story of penicillin isn't only about mold in a Petri dish, but about how scientific insight can transform public health, save millions of lives, and set new standards for global medicine.

?

What specific engineering innovations made deep-tank penicillin fermentation possible during WWII?

How did the Oxford team’s methods differ from Fleming’s original approach?

Why did U.S. agricultural by-products like corn-steep liquor prove pivotal for yield increases?

How did penicillin availability shape outcomes on the battlefield and home front during WWII?

What lessons from penicillin’s development inform today’s fight against antimicrobial resistance?

Dig Deeper

A concise history of Fleming’s observation and the wartime sprint that made penicillin a medical mainstay.

From a contaminated Petri dish to a global therapy: penicillin’s discovery and impact explained.

Related

The Properties of Water

Water isn’t just wet. It’s weird—and wonderful. From defying gravity in trees to sticking to itself in your bloodstream, water’s molecular magic is what makes life on Earth possible.

Macromolecules & The Chemistry of Life

Life is built on legos—but not the kind you step on barefoot. We're talking molecular legos: the macromolecules that fuel your body, build your cells, and store your DNA’s secrets.

The Ozone Hole: A Wake-Up Call from the Sky

In 1985, scientists discovered a gaping hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica. It wasn’t just a science headline—it was a planetary red flag. And the world actually listened.

Further Reading

Stay curious!