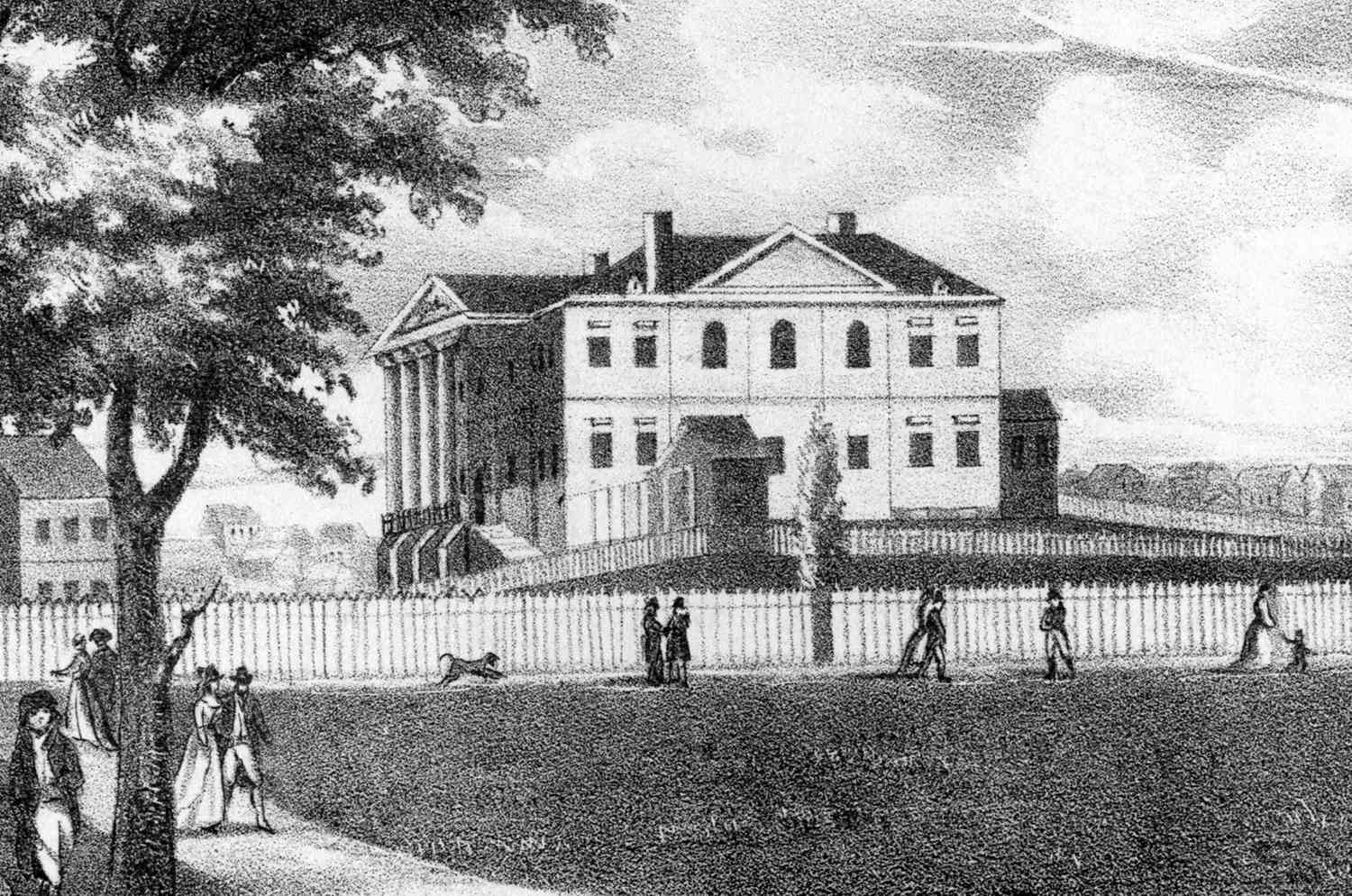

The White House Cornerstone Is Laid

On October 13, 1792, builders laid the cornerstone for the White House in Washington, D.C.—a symbol of American leadership and democracy.

What Happened?

After the Revolutionary War, the young United States needed a permanent capital. Philadelphia had served as the temporary seat of government, but leaders wanted a neutral location that represented all states, not just one. President George Washington chose land along the Potomac River—ceded by Maryland and Virginia—to build the new city of Washington, D.C.

French-born engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant designed the capital’s sweeping plan, full of grand avenues, open spaces, and circles that would symbolize democracy in motion. At the heart of his vision stood the President’s House—a place where the nation’s leader would live, work, and welcome guests from around the world.

On October 13, 1792, workers placed the first cornerstone of that home. The chosen design came from Irish-born architect James Hoban, who modeled the mansion after classical European styles meant to project strength and order. Washington oversaw the project but never lived to see it completed. Construction took eight years, and in 1800, President John Adams and First Lady Abigail Adams became its first residents.

Though the building represented the ideals of a new nation built on liberty, its creation depended on people who were denied that same freedom. Enslaved African Americans, along with free Black laborers, European immigrants, and local craftsmen, quarried stone, sawed timber, mixed mortar, and hauled supplies. Their names were rarely recorded, but their work remains in every wall and column of the White House.

In 1814, British troops invaded Washington during the War of 1812 and set fire to the President’s House, leaving only its charred stone shell. The building was rebuilt under the same architect, James Hoban, who added elegant porticos to the north and south sides. When reconstruction finished in the 1820s, the walls were painted white to hide the burn marks—a look that gave rise to the name 'The White House.'

Over the next two centuries, the White House grew alongside the presidency. Theodore Roosevelt expanded it in 1902 by adding the West Wing and moving the president’s office out of the family quarters. Later, Harry S. Truman ordered a full reconstruction after the old walls began to crack, rebuilding the interior from the ground up while preserving its historic shell.

Every president since John Adams has called the White House home. It has witnessed wars, peace treaties, civil rights marches, and moments that defined the nation’s story. Yet the house’s truest power lies not in its beauty but in its contradictions—a symbol of democracy built by those denied it, later serving as a place where freedom’s meaning continues to evolve.

When visitors walk past its white stone walls today, they see more than the home of a president. They see a living monument—built by many hands, across race and class—a reminder that democracy, like any great structure, is always under construction.

Why It Matters

The White House represents both the promise and the paradox of America: a nation founded on ideals of liberty, yet built through the labor of enslaved people. Understanding its origins helps us appreciate that democracy isn't a finished project but a work still being built by each generation. The house’s history teaches that symbols of power must also tell the truth about how that power was made.

?

Why did leaders choose Washington, D.C., to be the new nation’s capital?

What role did enslaved and free Black workers play in building the White House?

How has the White House changed over time to meet the needs of each generation?

What does the White House symbolize today, and how has that meaning evolved?

Why is it important to tell the full story of who built America’s landmarks?

Dig Deeper

Discover how the White House was built, rebuilt, and reimagined into a lasting symbol of American democracy.

Related

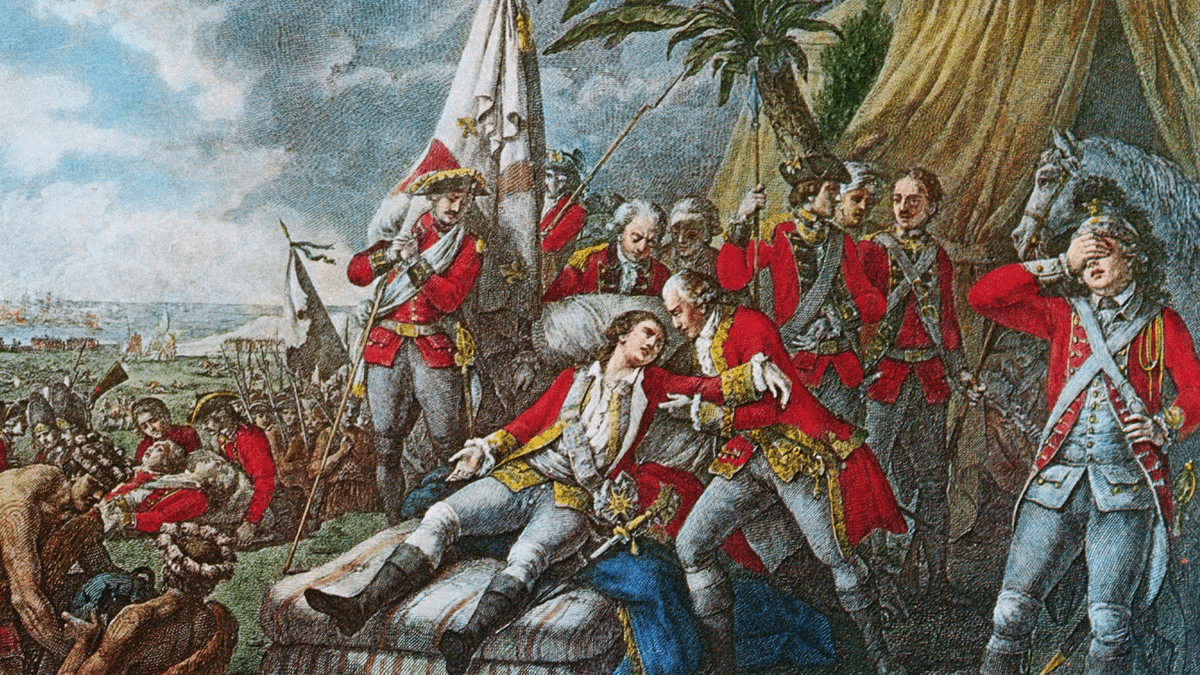

The French and Indian War: The Battle for North America

Before the American Revolution, another great war reshaped North America—the French and Indian War. It began as a fight over land and power, but ended up changing the map of the world and planting the seeds of independence.

American Revolutionary War: From Protest to a New Nation

How arguments over taxes and rights grew into an eight-year war—and how ideas, allies, and perseverance turned thirteen colonies into the United States.

The Constitutional Convention: Building a More Perfect Mess

In the summer of 1787, 55 men locked themselves in a room to fix the government—and ended up rewriting it from scratch. What came out wasn’t perfect, but it changed everything.

Further Reading

Stay curious!