Chicago’s Freedom Day School Boycott

Freedom Day was one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in the North.

What Happened?

Nearly a decade after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision declared school segregation unconstitutional, Chicago’s public schools remained divided by race and inequality. Schools in Black neighborhoods were overcrowded, underfunded, and crumbling, while white schools nearby had open seats and modern facilities.

The problem wasn’t an official law but a web of racist housing policies and school zoning lines. Redlining—the practice of denying loans and investment to Black neighborhoods—kept many African Americans trapped in certain districts. The Chicago Board of Education then used a 'neighborhood schools' policy to keep students from crossing racial boundaries, effectively maintaining segregation.

Under Superintendent Benjamin Willis, the city refused to integrate. When Black schools became overcrowded, instead of allowing students to attend nearby white schools, Willis placed aluminum mobile units in playgrounds and parking lots. Parents nicknamed them 'Willis Wagons,' and they became symbols of Chicago’s educational apartheid.

Community frustration boiled over in 1963. Parents, teachers, clergy, and activists (including Martin Luther King Jr.) joined together to organize a citywide school boycott called 'Freedom Day.' They demanded smaller class sizes, equal funding, and the right for Black students to attend any public school regardless of neighborhood.

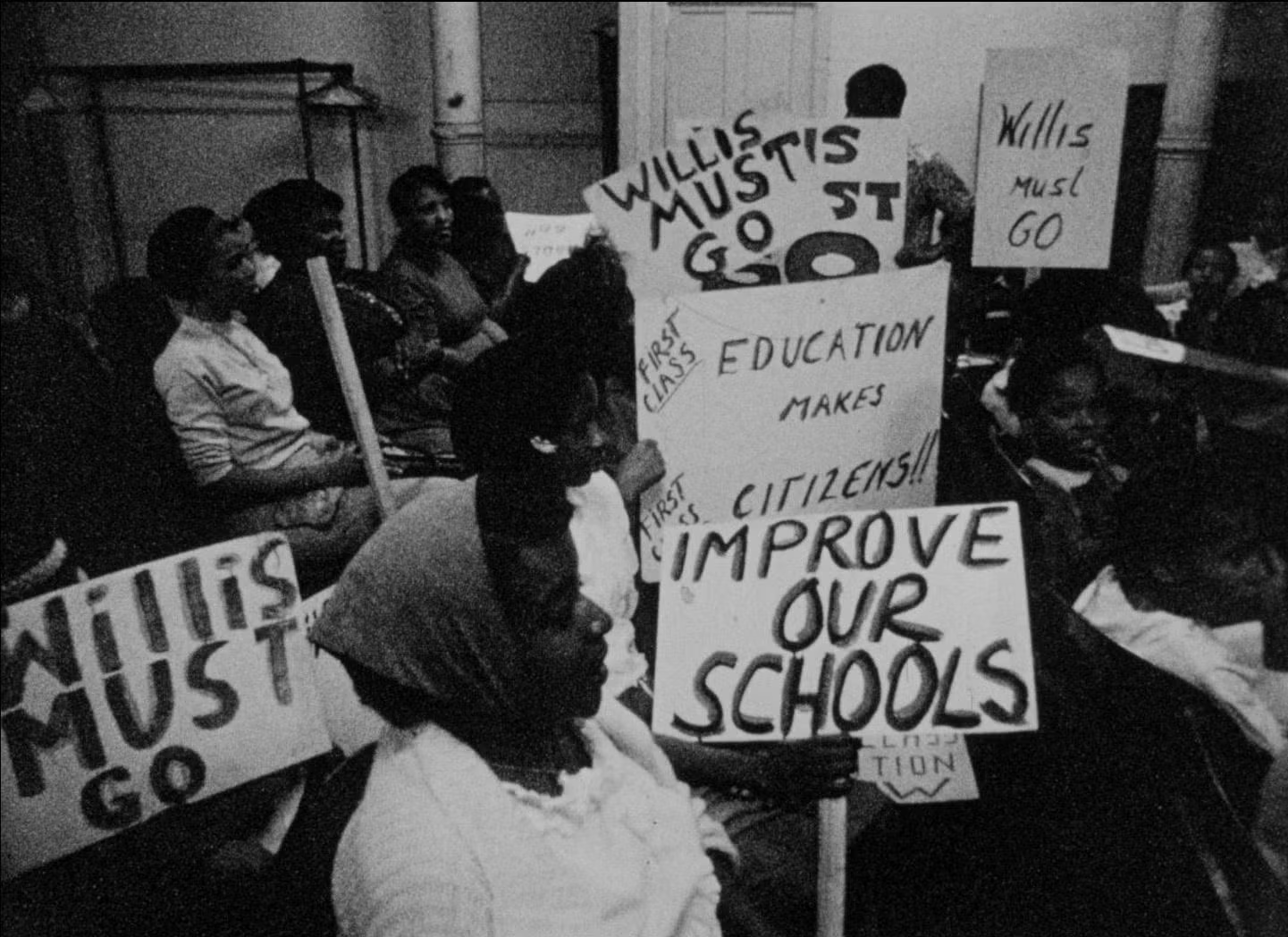

On October 22, 225,000 students stayed home from school in solidarity. Ten thousand marchers gathered downtown at City Hall and the Board of Education, chanting, holding signs, and demanding Willis’s resignation. Many children attended temporary 'Freedom Schools,' where they learned lessons on civil rights, history, and civic participation.

The protest was peaceful, massive, and impossible to ignore. It drew attention from national media and showed that northern cities, not just the South, were guilty of educational segregation. Yet Superintendent Willis refused to step down, and Chicago’s schools remained deeply unequal.

Though the boycott didn’t immediately bring reform, it was a turning point. It proved that parents and students could use collective action to demand fairness and dignity in education. It also helped launch the Chicago Freedom Movement, which would later bring Dr. King and national civil rights leaders to the city to fight for equal housing and opportunity.

Freedom Day reminds us that civil rights are not just about voting or buses—they’re about classrooms, resources, and the belief that every child deserves the same chance to learn. The students and parents who stood up that day carried forward the message that justice in education is a cornerstone of democracy.

Why It Matters

Even today, the legacy of Freedom Day lives on. Many American cities still face educational inequality shaped by race and neighborhood wealth. Remembering this movement challenges us to keep working toward the promise of truly equal education for all. The Chicago Freedom Day boycott showed that the fight for civil rights was national, not regional. It exposed how northern cities used zoning, funding, and school placement to enforce racial segregation long after it was outlawed. The courage of students and parents demonstrated the power of community activism in holding leaders accountable and pushed education equality to the forefront of the civil rights agenda.

?

What does 'de facto segregation' mean, and how did it affect Chicago’s schools in the 1960s?

Why did the use of 'Willis Wagons' become such a powerful symbol of inequality?

How did housing discrimination like redlining influence access to education?

Why was the Chicago school boycott significant in the larger Civil Rights Movement?

How does the legacy of Freedom Day still relate to education and civil rights today?

Dig Deeper

A documentary connecting the 1963 Chicago school boycott to ongoing issues of race, education, and youth activism.

Filmmaker Gordon Quinn explores how the 1963 school boycott helped shape modern education and civil rights movements.

Related

Montgomery Bus Boycott, Greensboro Sit-In, and the Rise of MLK

From Montgomery’s buses to Greensboro’s lunch counters, ordinary citizens ignited extraordinary change — and a new national leader emerged.

MLK the Disrupter and the Poor People’s Campaign

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final chapter was about more than civil rights—it was a bold demand for economic justice that challenged the nation’s values at their core.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Enforcing the 15th Amendment

How a landmark law transformed voting access in the South and gave real force to the promises of the 15th Amendment.

Further Reading

Stay curious!