Confucius

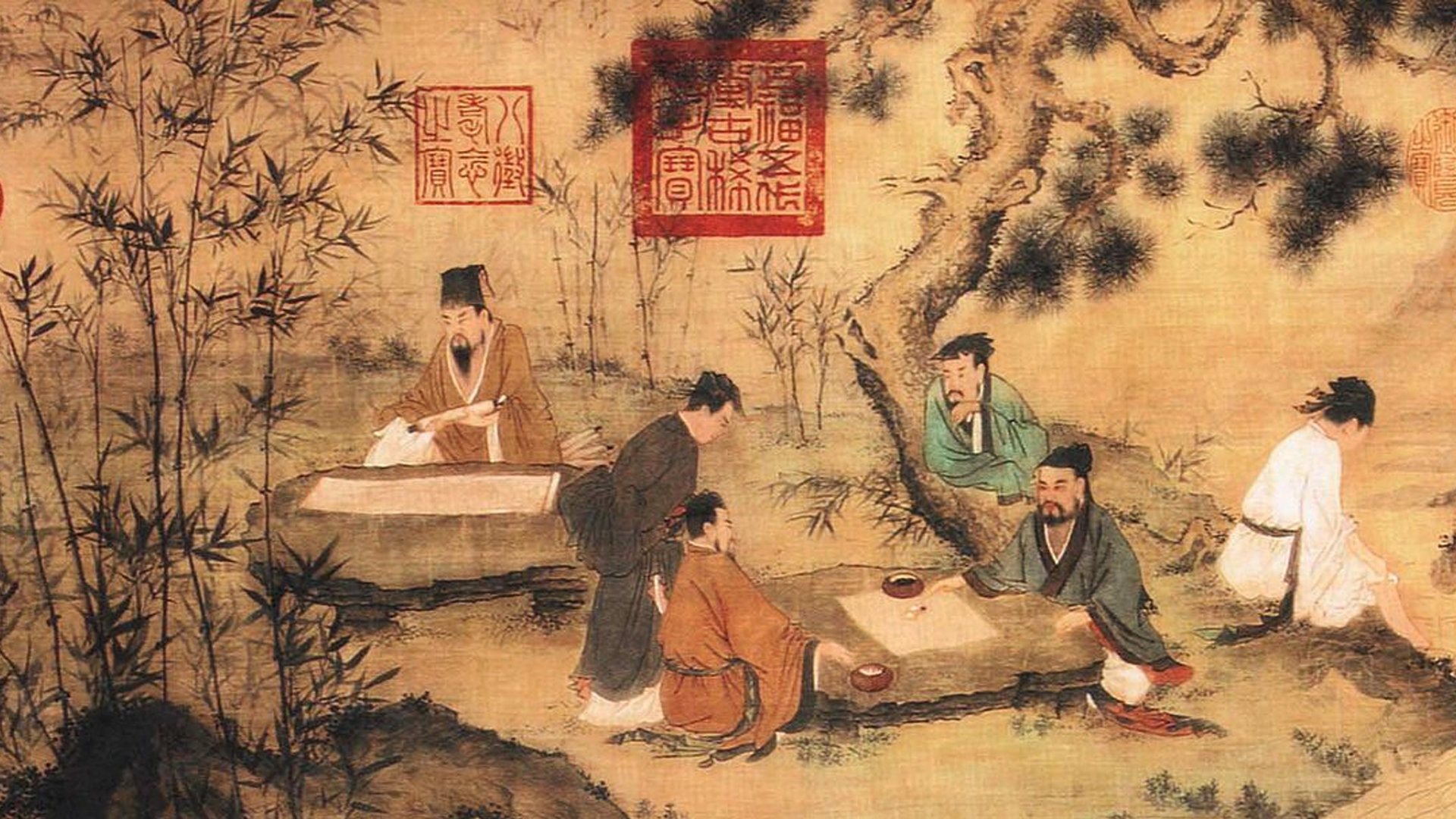

Confucius, known as Master Kong, teaching disciples beneath pine trees with bamboo scrolls and ritual vessels nearby.

Biography

Confucius (Kongzi) was born in 551 BCE in the state of Lu (modern day Shandong, China). His father died when he was still a boy, so his family didn’t have much. But Confucius loved learning. He trained in what people called the “six arts”: ritual (how to treat others respectfully), music, archery, driving chariots, writing, and math. He believed education should shape character, not just sharpen talent. That education was about becoming a good person.

In his early 20s, Confucius worked simple jobs, like looking after grain stores and herding animals, later rising to posts like minister of works and minister of crime. Government service taught him laws and punishments weren’t enough to keep society peaceful. They require virtue at the top and trust between leaders and the people.

Around his 30s, Confucius began to teach. Back then, schools were mostly for rich kids, but he broke with tradition by welcoming students from many backgrounds, not just aristocrats. In his view, anyone who loved learning and practiced self-discipline could become a "junzi"—a cultivated person. His classroom centered on conversation, reflection, and classic texts, training students to connect knowledge with daily conduct.

Two core ideas anchor his thought. First is Ren (humaneness): the habit of considering others—"Do not impose on others what you do not desire for yourself." Second is Li, meaning respect—following good habits and behaviors that keep families, friendships, and communities strong. To Confucius, respect wasn’t about fancy ceremonies. It was the everyday actions that showed care and kindness.

Confucius also taught that good government begins with self-government. Leaders should model integrity, correct their own faults, and win the people’s trust. "The virtue of those above is like the wind; the virtue of those below is like the grass. When the wind blows, the grass bends." In other words, if leaders were honest and kind, the people would be, too. Sadly, many rulers didn’t want to hear this, so Confucius spent years traveling among neighboring states seeking a ruler brave enough to follow his advice.

During his travels, he and his students sharpened ideas that would outlast their setbacks: education for character, leaders should guide with fairness as a moral example, and the power of culture—poetry, music, history—to shape the heart. Confucius called himself a transmitter, not a creator. He often gave his students one part of a lesson and told them to figure out the rest themselves, pushing them to think for themselves.

Late in life, Confucius returned home to teach, edit the classics, and mentor a growing circle of students. His students wrote down their conversations with him, and these became a book called the Analects, a book that reads like a workshop on living well: how to listen, speak honestly, keep promises, correct mistakes, and practice courage without arrogance.

Confucius died in 479 BCE believing his reforms had fallen short and that he had failed in his mission. But history proved him wrong. His teachings spread far and wide, across dynasties and borders, his ethics shaped schools, families, and governments. His ideas became the language of everyday life, reminding people that personal virtue—being a good and honest person—was the foundation for a peaceful society.

Confucius believed that being a good person makes the whole world better. Rules and punishments can only do so much, what really holds a community together is trust, kindness, and respect in everyday life. He showed that anyone can learn, anyone can grow, and that leaders should guide by setting a good example. His lesson is clear: start with yourself. If you are honest, caring, and responsible, you make your family, your school, and your community stronger. That’s not just old wisdom, it’s a guide for how we can all help build a fairer, kinder world today.

?

How do ren (humaneness) and li (ritual) work together to shape behavior in daily life?

What does Confucius mean by leadership through moral example rather than punishment?

How did Confucius change who could access education, and why did that matter?

Where might Confucian ideas support modern civic life—and where might they be challenged?

What can the Analects teach about correcting mistakes and building trust?

Dig Deeper

A clear, animated overview of Confucius’s life, core ideas, and lasting influence on East Asian civilization.

Explores how tradition, order, and moral cultivation shape Confucius’s approach to personal and political life.

Discover more

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau reimagined modern freedom, education, and democracy through his social contract theory and philosophy of natural human goodness.

Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Gandhi led India’s fight for independence through a radical commitment to nonviolence and truth.

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela was a South African freedom fighter who spent 27 years in prison for resisting apartheid and became the country’s first Black president.

Further Reading

Stay curious!