The Market Revolution: How Innovation Transformed America

The Market Revolution connected people, goods, and ideas—while also revealing deep inequalities in who benefited from progress.

The Dive

In the early 1800s, the United States was still a young, mostly rural nation. Most families lived on small farms, growing their own food and making what they needed. But by mid-century, America was rapidly changing. A wave of inventions, new businesses, and ambitious infrastructure projects sparked what historians call the Market Revolution, a transformation that turned local economies into a national network of trade and industry. Farmers, merchants, and workers were no longer isolated; they were part of a growing web of production and exchange.

At the heart of this transformation was technology. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, invented in 1793, made it possible to clean cotton fifty times faster than before. This boosted the Southern cotton industry and fueled America’s rise as a global supplier of textiles. But the invention also deepened the nation’s dependence on slavery. As cotton profits soared, so did the demand for enslaved labor, spreading plantation agriculture across the South and entrenching racial inequality even further.

Meanwhile, in the North, water-powered textile mills transformed how goods were made. Towns like Lowell, Massachusetts became centers of early industrial life, where young women (known as the 'Lowell Mill Girls') worked long hours spinning and weaving cloth in factories. For many, mill work offered independence and wages, but also brought harsh conditions and limited rights. Women’s labor fueled the nation’s first industrial boom, yet they remained excluded from political and economic equality.

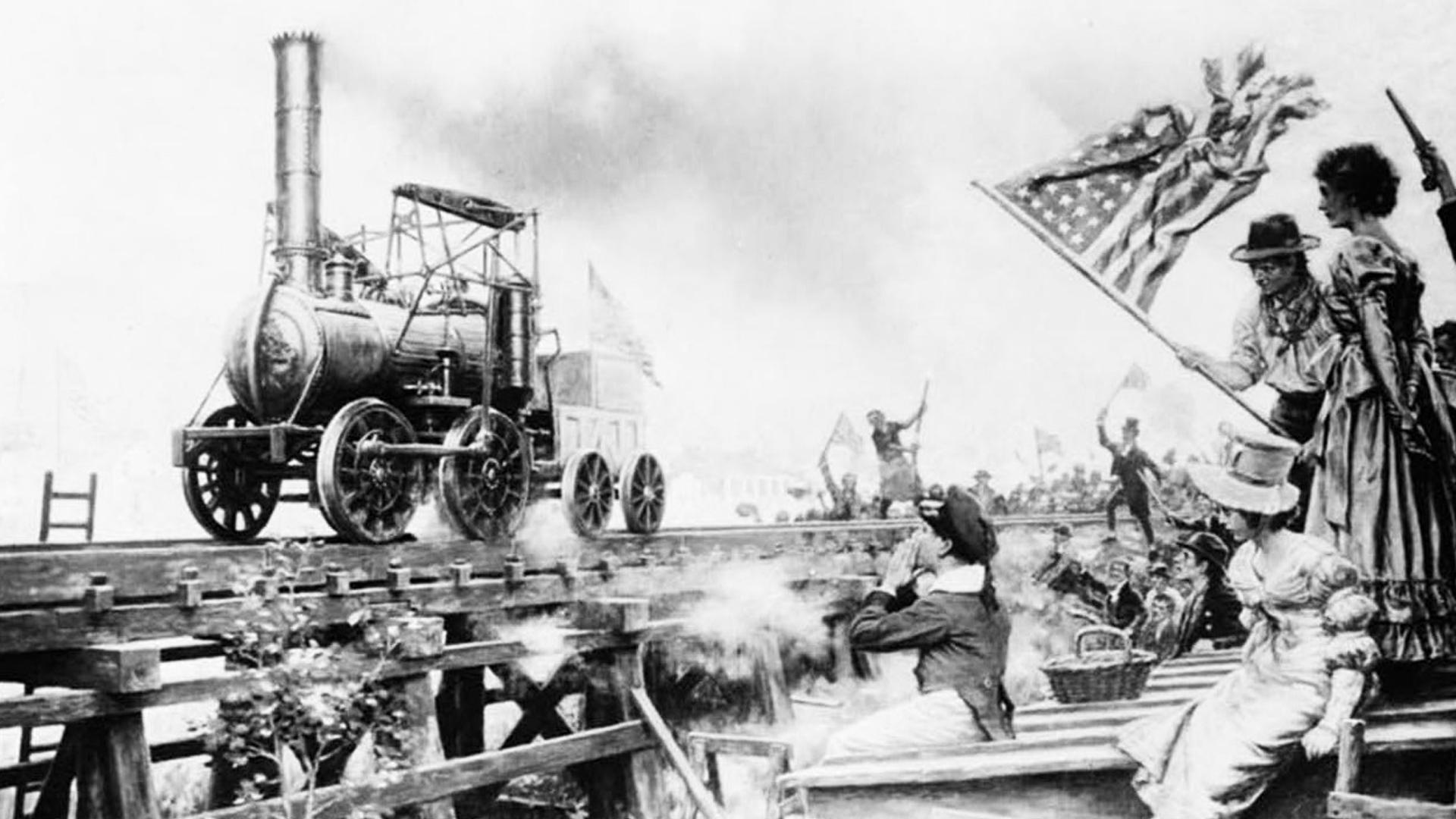

Transportation was another key driver of change. The construction of canals, roads, and railroads opened new routes for goods and people. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, connected the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, slashing shipping costs and turning New York City into the nation’s leading port. Railroads soon followed, stitching together distant towns and markets. In places like North Carolina’s Piedmont region, new rail lines allowed farmers to sell their crops beyond local markets, linking rural communities to the wider economy for the first time.

As industries expanded, so did cities. Merchants and craftsmen found new opportunities in growing towns, while free Black artisans, laborers, and entrepreneurs built businesses despite facing discrimination and legal barriers. Immigrants from Ireland and Germany provided much of the workforce that powered industrial growth. Yet while the new economy offered jobs and upward mobility for some, it left others behind, particularly women, people of color, and enslaved laborers who were denied fair wages or freedom entirely.

The Market Revolution also changed how people lived and thought. Families that once worked together on farms began to earn wages in factories. Goods that were once handmade at home were now mass-produced. Telegraph lines allowed people to communicate across hundreds of miles, and newspapers spread information faster than ever before. These changes brought convenience and connection, but also created new pressures, like long workdays, economic inequality, and environmental strain.

Government policy played a major role in supporting this expansion. The federal government funded roads and canals, protected inventors with patents, and encouraged westward settlement through land grants. Entrepreneurs and inventors responded with a wave of innovation: Samuel Morse’s telegraph connected cities through instant communication; Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper made farming more efficient; and steam engines powered everything from riverboats to factories. America was becoming a nation driven by invention and ambition.

But the benefits of growth were not shared equally. The wealth generated by trade and industry was concentrated in cities and among business owners, while laborers faced low pay and little protection. In the South, enslaved people bore the heaviest cost of progress—working under brutal conditions to produce the cotton that fed Northern mills and European markets. Economic expansion strengthened both opportunity and oppression, revealing how progress can lift some while trapping others.

By the 1840s, the United States had become a nation on the move. Its cities buzzing, its farms connected, and its people caught between tradition and transformation. The Market Revolution reshaped not only the economy but also American identity. It encouraged innovation and ambition, yet forced the nation to confront deep questions about justice, labor, and equality. The same forces that fueled growth would later ignite new conflicts over slavery, workers’ rights, and who truly benefited from the promise of progress.

Why It Matters

The Market Revolution was one of the most transformative periods in American history. It connected farms to factories, regions to nations, and ideas to industries. But it also exposed deep divides in wealth, race, and opportunity. Understanding this era helps us see how technology and trade can both create progress and inequality and reminds us that every revolution, economic or otherwise, has winners and losers. The choices made in this period shaped America’s economy, its social fabric, and its future conflicts over freedom and fairness.

?

How did inventions like the cotton gin and telegraph change the way Americans lived and worked?

Why did the Market Revolution increase the need for enslaved labor in the South?

What opportunities and challenges did women face while working in early factories?

How did improvements in transportation and communication connect different regions of the country?

Who benefited most from America’s economic growth—and who was left out?

Dig Deeper

A fast-paced overview of how technology, transportation, and new markets changed life in early 19th-century America.

Related

Early Industry and Economic Expansion (1800–1850)

From gold mines in North Carolina to textile mills and telegraphs, discover how the Market Revolution transformed the way Americans lived, worked, and connected in the early 19th century.

The Gilded Age, Industrialization, and the 'New South'

A glittering era of innovation and industry, the Gilded Age promised progress but delivered inequality. In the South, leaders dreamed of a 'New South,' yet industrialization offered opportunity for some while reinforcing systems of poverty and discrimination for others.

The American Civil War – A Nation Torn Apart

From Fort Sumter to Appomattox, the Civil War was the deadliest conflict in U.S. history, fought over the nation's most profound moral and political divisions.

Further Reading

Stay curious!