The Gilded Age: Glitter, Growth, and the Cost of Progress

The Gilded Age was a period of explosive industrial growth, urban expansion, and technological innovation in the United States.

The Dive

Between about 1870 and 1900, the United States changed faster than ever before. Railroads stretched across the country, factories filled cities with smoke and noise, and enormous fortunes were made almost overnight. This period became known as the Gilded Age, a name coined by Mark Twain to describe a society that looked shiny and successful on the outside but hid deep problems underneath. The Gilded Age was an era of invention, growth, and opportunity—but also of inequality, exploitation, and corruption.

After the Civil War, America shifted from a mostly agricultural nation to an industrial one. Factories replaced small workshops, and corporations replaced family businesses. Railroads became the backbone of the economy, moving people, raw materials, and finished goods across long distances. The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 connected the East and West, helping towns grow and markets expand. New inventions—like safer air brakes, sleeping cars, and electric lighting—made travel and city life easier and more comfortable for many Americans.

This industrial boom created new kinds of jobs, not just on factory floors but in offices, stores, and management. A growing middle class began to enjoy consumer goods, department stores, advertisements, and entertainment. For some, the Gilded Age felt like progress in motion.

In the South, leaders promoted a vision called the “New South,” which aimed to move beyond farming and rebuild the region through industry. North Carolina became a leader in this effort. Tobacco companies in Durham, especially the American Tobacco Company, grew into global giants. Textile mills and furniture factories expanded in towns like High Point, drawing in poor white farmers looking for steady wages.

But these jobs came at a cost. Workdays often lasted 12 hours or more, pay was low, and factories were dangerous. Child labor was common, with children as young as eight working long shifts in textile mills. While the economy grew, the people powering it often remained trapped in poverty.

The wealth of the Gilded Age was not shared equally. African Americans in the South faced harsh limits under Jim Crow laws, which enforced segregation and stripped away political rights. Many were forced into low-paying jobs or back into farming as sharecroppers, locked into cycles of debt with little chance to escape.

Immigrants crowded into cities like New York and Chicago, working long hours in unsafe factories for very little pay. Cities were unprepared for this growth. Tenements were overcrowded, sanitation was poor, and disease spread quickly. While industrial leaders lived in massive mansions like Biltmore in North Carolina, millions of workers struggled just to survive.

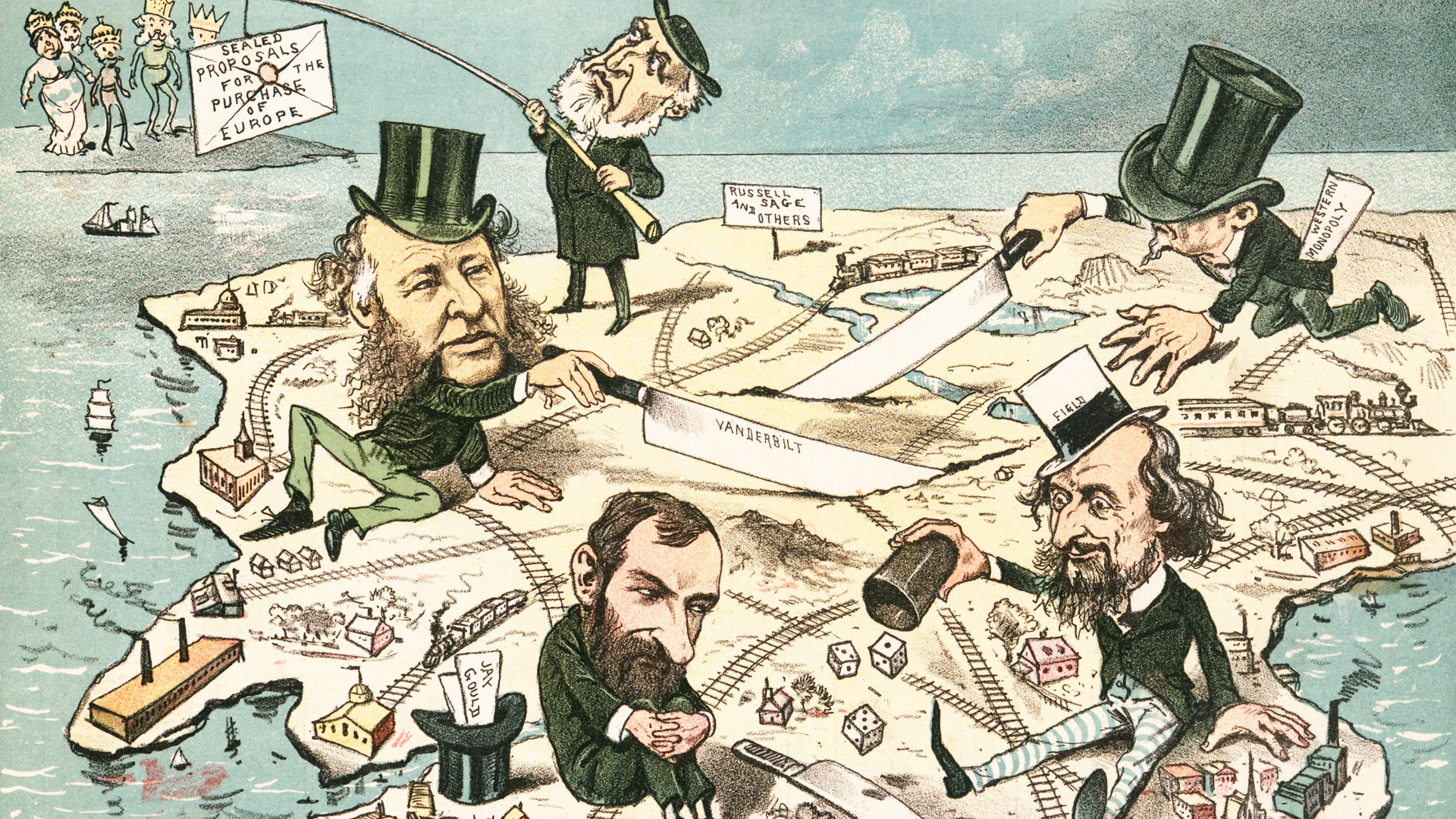

The Gilded Age also produced powerful industrialists known as “robber barons.” Railroad, oil, steel, and banking tycoons used monopolies, political influence, and harsh labor practices to dominate entire industries. Some justified inequality through Social Darwinism, arguing that wealth proved moral superiority.

At the same time, resistance grew. Workers organized labor unions and staged strikes demanding better wages and safer conditions. Farmers formed political movements like the Populist Party to challenge railroad power and government corruption. Journalists called muckrakers exposed injustice and abuse, forcing the public to confront the darker side of American success.

By the 1890s, it became clear that the extreme inequality of the Gilded Age could not last. Economic crises like the Panic of 1893 left millions unemployed and angry. This frustration helped spark the Progressive Movement, which pushed for reforms such as labor protections, antitrust laws, food safety rules, and expanded democracy. These changes began to shift power away from monopolies and toward ordinary citizens.

Why It Matters

The Gilded Age reminds us that progress is complicated. Innovation and growth can bring opportunity, but without fairness, they can also deepen inequality. Understanding the successes and failures of this era helps us think critically about how to create a future where economic growth benefits everyone, not just those at the top.

?

Why did Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner choose the word 'gilded' to describe this period?

How did the 'New South' vision differ from the pre-Civil War Southern economy?

What challenges did workers—especially women and children—face in mills and factories?

How did Jim Crow laws shape opportunities for African Americans in the South?

What parallels can we draw between the economic inequality of the Gilded Age and today?

Dig Deeper

Gilded Age politics, economic change, and the rise of inequality in late 19th-century America.

An overview of the post-Reconstruction expansion of industrialism in the United States.

Related

The Market Revolution: How Innovation Transformed America

In the early 1800s, America changed from a land of small farms to a booming nation of factories, railroads, and markets. The Market Revolution connected people, goods, and ideas—while also revealing deep inequalities in who benefited from progress.

Early Industry and Economic Expansion (1800–1850)

From gold mines in North Carolina to textile mills and telegraphs, discover how the Market Revolution transformed the way Americans lived, worked, and connected in the early 19th century.

Jim Crow and Plessy v. Ferguson

After Reconstruction, the South built a legal system to enforce racial segregation and strip African Americans of political power. The Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 made 'separate but equal' the law of the land—cementing injustice for decades.

Further Reading

Stay curious!