Montgomery Bus Boycott, Greensboro Sit-In, and the Rise of MLK

From Montgomery’s buses to Greensboro’s lunch counters, ordinary citizens ignited extraordinary change — and a new national leader emerged.

The Dive

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–56) began when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger, defying a local law. This single act of courage ignited a 381-day protest in which about 90% of Montgomery’s Black citizens refused to ride the buses. The boycott was carefully organized: carpools were set up, community meetings were held, and church leaders coordinated efforts. At the forefront was a young pastor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose speeches and leadership drew national attention. The Supreme Court eventually ruled bus segregation unconstitutional, making the boycott one of the first major victories of the Civil Rights Movement.

The boycott proved that coordinated, nonviolent mass protest could work, not just as a moral statement, but as a practical strategy for forcing legal change. It also showcased the role of everyday people, particularly Black women in Montgomery, who were the backbone of the organizing, the walking, and the persistence that kept the boycott alive for over a year.

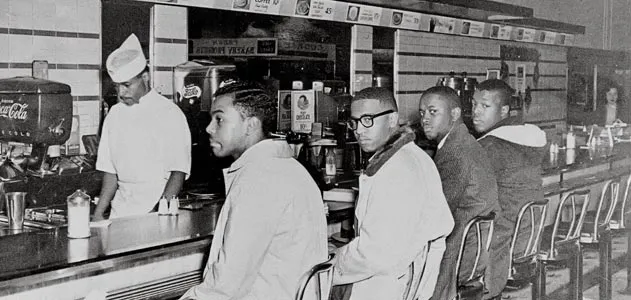

Four years later, the fight moved from buses to lunch counters. On February 1, 1960, four Black college students, Ezell Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, walked into a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat at a 'whites-only' lunch counter, and politely asked for service. They were refused, but they stayed seated. The next day they returned with more students. Within weeks, sit-ins spread to dozens of cities across the South, drawing hundreds of young people into the movement.

The Greensboro Sit-In showed the power of youth-led, nonviolent direct action. It also revealed the emotional force of visible injustice — watching neatly dressed, polite students be denied service simply because of their skin color shocked many Americans. The sit-in inspired the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which would go on to play a major role in civil rights campaigns throughout the decade.

In the years between Montgomery and Greensboro, Martin Luther King Jr. co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization dedicated to nonviolent protest and the broader fight for civil rights. These two early victories cemented his role as a national figure, not because he acted alone, but because he became a powerful voice for a movement built on thousands of ordinary people taking extraordinary risks.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Greensboro Sit-In teach us that systemic change often begins with local acts of courage. They remind us that strategies like boycotts and sit-ins are not spontaneous; they require planning, discipline, and solidarity. And they prove that when ordinary citizens, whether working women in Montgomery or college students in Greensboro, commit themselves to justice, they can reshape the laws, the culture, and the conscience of a nation.

Why It Matters

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and Greensboro Sit-In were more than isolated protests — they were blueprints for a movement. They proved that nonviolent resistance, when organized and sustained, could dismantle unjust laws and inspire nationwide change. They also revealed that young people and everyday citizens, not just prominent leaders, are often the ones who light the spark for transformative justice.

?

Why did the Montgomery Bus Boycott succeed where other protests had failed?

What made the Greensboro Sit-In such a powerful example of youth activism?

How did Martin Luther King Jr.’s leadership style influence the outcome of these early civil rights actions?

In what ways do boycotts and sit-ins differ as protest strategies, and what do they have in common?

How might these strategies be used to address social justice issues today?

Dig Deeper

A detailed look at the 381-day boycott in Montgomery and its impact on the Civil Rights Movement.

A first-hand reflection on the courage of the Greensboro Four and the sit-in movement they inspired.

An exploration of King’s life, philosophy of nonviolence, and leadership in the Civil Rights Movement.

Related

The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle, Solidarity, and Social Change

From classrooms to courthouses, buses to bridges, the Civil Rights Movement reshaped America’s laws — and its conscience.

MLK the Disrupter and the Poor People’s Campaign

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final chapter was about more than civil rights—it was a bold demand for economic justice that challenged the nation’s values at their core.

Universal Suffrage in the United States

The right to vote wasn’t handed to everyone—it was fought for, over centuries, by people demanding that democracy actually mean everyone has a voice.

Further Reading

Stay curious!