Separation of Powers

Explore the principle of seperation of powers.

The Dive

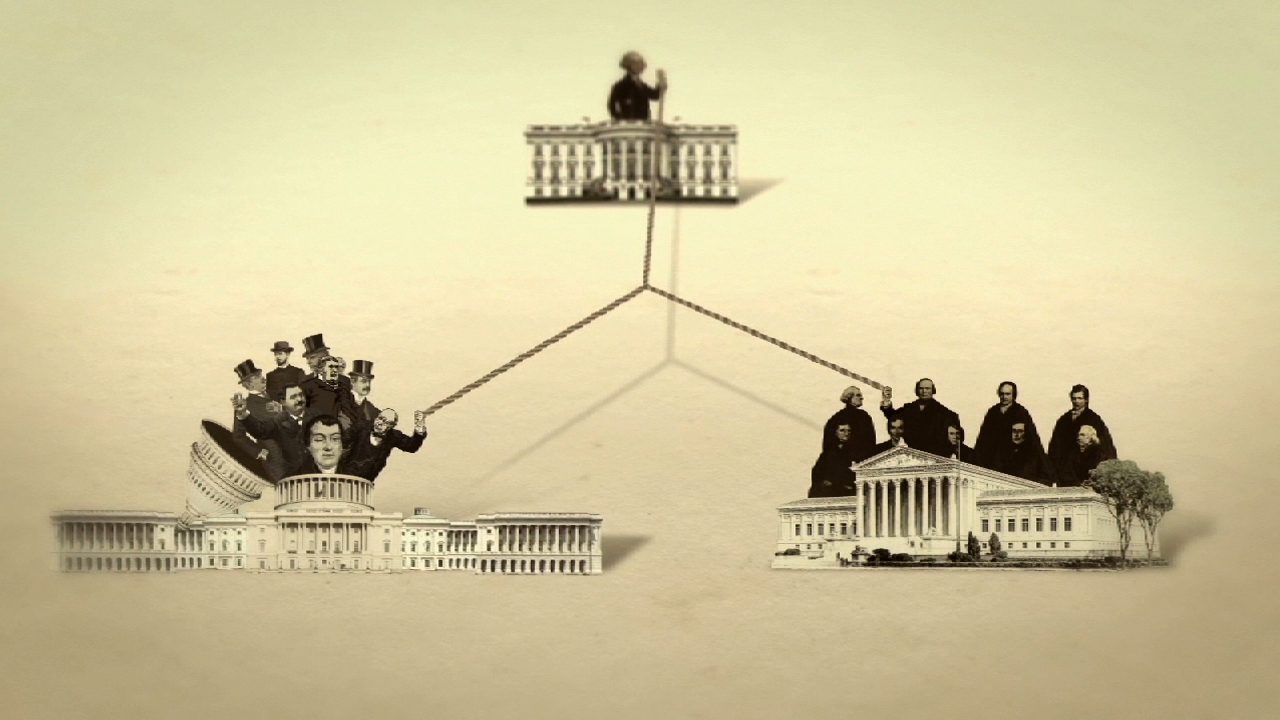

When the framers of the U.S. Constitution gathered in Philadelphia in 1787, they were determined to build a government that would never again resemble the unchecked power of a king. Having lived under British rule, they had seen how too much authority in one place could lead to abuse, corruption, and the loss of individual rights. Their solution was simple yet revolutionary: divide power among three separate branches of government, each independent, yet interdependent, so that no single branch could dominate the others.

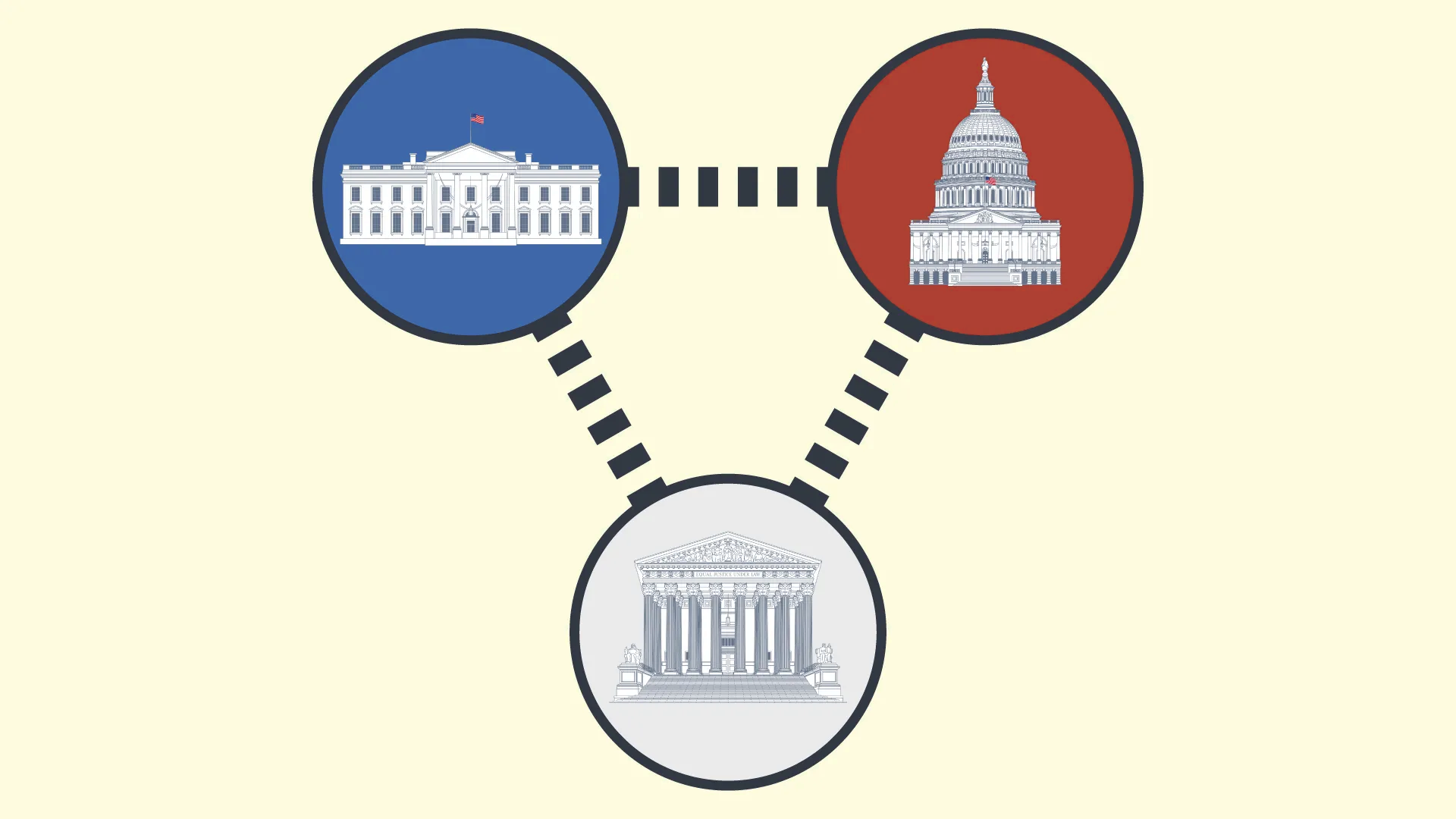

Article I of the Constitution gives the legislative branch, Congress, the power to make laws. Congress is divided into two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. This design balances the will of the people, represented by population in the House, with the equal voice of each state in the Senate. Congress debates, drafts, and passes legislation, oversees federal spending, and holds the unique authority to declare war. Its power, however, is not absolute.

Article II creates the executive branch, led by the President. The President enforces the laws passed by Congress, serves as commander in chief of the armed forces, negotiates treaties (with Senate approval), and appoints judges, ambassadors, and cabinet members. But the President’s actions are checked at every step. Congress can override a presidential veto with a two-thirds vote, limit funding for executive programs, and even impeach and remove the President from office if necessary.

Article III establishes the judicial branch, headed by the Supreme Court and supported by lower federal courts. The judiciary’s primary responsibility is to interpret laws and determine whether they align with the Constitution. This authority, known as judicial review, was confirmed in the landmark case 'Marbury v. Madison' (1803). Through this power, the courts can strike down laws or executive actions that violate constitutional principles, ensuring that both Congress and the President remain within their constitutional limits.

The framers also understood that a functioning democracy requires cooperation as much as competition. The branches were designed to share powers in ways that require negotiation. The President proposes budgets, but Congress must approve them. The Senate confirms judges, but the President appoints them. The courts may interpret laws, but they cannot enforce them without the executive branch. This dynamic tension, what James Madison called ‘ambition counteracting ambition’, is the engine that keeps government balanced.

Over the centuries, the Supreme Court has played a crucial role in interpreting the boundaries of these powers. Cases such as 'Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer' (1952) limited presidential authority, while 'United States v. Nixon' (1974) affirmed that even the President is not above the law. These decisions remind us that the Constitution is a living document, designed to adapt to the challenges of new generations while preserving the principle of limited government.

The separation of powers also extends beyond the federal level. State governments mirror this structure, maintaining their own legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This layered system, known as federalism, ensures that power is further distributed between national and state authorities, preventing any single level of government from overwhelming citizens’ rights.

In everyday life, separation of powers might seem invisible, but it touches everything. When Congress debates environmental laws, when the President signs an executive order, or when a court rules on a civil rights case, each branch is performing its unique duty within this framework. The friction between them isn’t a flaw; it’s the feature that keeps liberty alive.

Why It Matters

The separation of powers is the backbone of American democracy by forcing collaboration, demanding accountability, and ensuring that no leader, no matter how popular or powerful, can rule alone. It’s the invisible architecture of freedom, still holding strong more than two centuries later. By understanding how the legislative, executive, and judicial branches share and limit authority, citizens gain insight into how freedom is preserved, and how it can be lost. When one branch overreaches, the others can act as guardians of balance. Knowing how these systems work equips people to recognize abuses of power, demand accountability, and participate meaningfully in the democratic process.

?

Why did the framers believe that dividing power among three branches was essential for liberty?

How do checks and balances prevent any one branch from becoming too powerful?

Can you think of modern examples where the branches of government have disagreed or limited each other’s power?

Why do you think the framers allowed some overlap in the powers of the three branches?

How does the separation of powers affect your daily life as a citizen?

Dig Deeper

A short and engaging overview of how the three branches of government share and limit power in a democracy.

Related

Democracy: Government by the People

Democracy is more than voting every few years. It is a way of sharing power, protecting rights, and making sure ordinary people have a real voice in how they are governed.

Building a New Nation: Foundations of State and National Government

From the shaky Articles of Confederation to the Constitution and Bill of Rights, discover how America’s founders navigated the turbulent waters of self-government—and why North Carolina took its time joining the party.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: The Battle That Built the Constitution

One side feared chaos. The other feared tyranny. Together, they gave us the Constitution—and the Bill of Rights.

Further Reading

Stay curious!