Universal Suffrage in the United States

Universal suffrage means that nearly all adult citizens have the right to vote, regardless of gender, race, wealth, or social status.

The Dive

At its core, universal suffrage is the idea that every adult citizen—no matter their race, gender, wealth, education, or background—should have the right to vote. It sounds simple, but in practice, it’s been one of the hardest promises for American democracy to keep.

The U.S. didn’t start out with anything close to universal suffrage. In the early days, only white, property-owning men could vote. By the mid-1800s, pressure from working-class movements helped end property requirements for white men, but millions—including women, Black Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, and the poor—were still excluded.

The Civil War and the abolition of slavery brought new opportunities and challenges. The 15th Amendment (1870) gave Black men the right to vote (on paper) but Southern states quickly used poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence to shut them out. Meanwhile, women’s rights leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony fought to include women in these protections, launching the first national petition drive for universal suffrage.

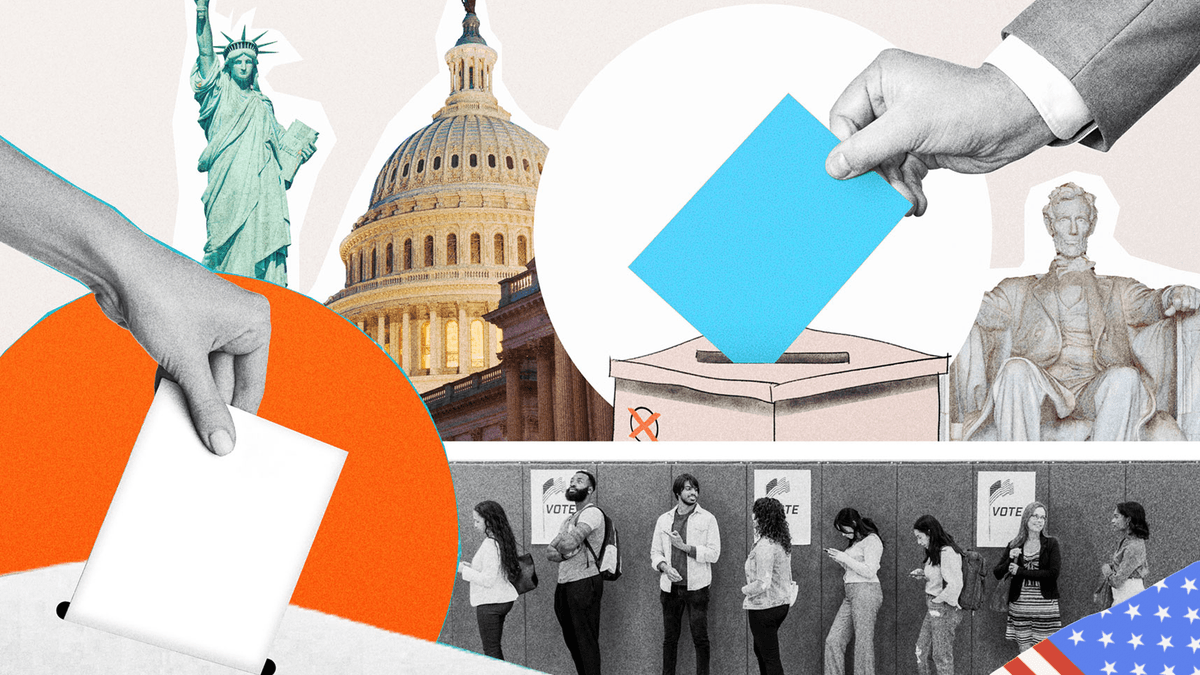

Major victories came slowly but powerfully: the 19th Amendment (1920) extended voting rights to women; the Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled many racist barriers; and the 26th Amendment (1971) lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, a direct response to young people protesting that if they were old enough to fight in Vietnam, they were old enough to vote.

Yet universal suffrage in America is still unfinished. Nearly 4 million Americans can’t vote due to felony convictions, even though three-quarters of them live outside prison walls. About 21 million lack the required photo ID to vote in certain states, disproportionately affecting Black, Latino, low-income, and elderly voters.

Noncitizens (around 22 million U.S. residents) live, work, pay taxes, and even serve in the military, but have no say in choosing leaders who make laws that affect them. Advocates argue that restoring immigrant voting rights would align U.S. practices with its democratic ideals, echoing past movements that expanded the vote to other excluded groups.

The fight for universal suffrage isn’t just about ballots—it’s about power. Without the vote, communities are vulnerable to laws and policies that ignore or harm them. History shows that voting rights are never simply given. They’re won through struggle, solidarity, and relentless pressure on the system.

Why It Matters

Universal suffrage is the backbone of a functioning democracy. Without it, large parts of the population remain politically invisible, and laws can be shaped without considering their needs or voices. History shows that voting rights expansions have transformed American society, but also that those rights can be rolled back. Understanding this struggle reminds us that democracy isn’t self-sustaining, it requires active defense and continued work to ensure every voice is heard.

?

What groups in U.S. history have been excluded from voting, and how did they win the right to vote?

Why do some people today still lack voting rights despite being U.S. residents?

How do voter ID laws and felony disenfranchisement affect democracy?

Should noncitizens be allowed to vote in U.S. elections? Why or why not?

What strategies have historically been effective in expanding voting rights?

Dig Deeper

Explore how voting rights in the U.S. have expanded—and in some cases, contracted—since 1789.

Dive into four different voting systems and examine which produces the fairest results.

A broad overview of how elections work in the U.S. and the laws that shape them.

Related

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Enforcing the 15th Amendment

How a landmark law transformed voting access in the South and gave real force to the promises of the 15th Amendment.

What Is Civics?

Civics is the study of how citizens participate in democracy—and why their participation matters.

Democracy: Government by the People

Democracy is more than voting every few years. It is a way of sharing power, protecting rights, and making sure ordinary people have a real voice in how they are governed.

Further Reading

Stay curious!