1900: The U.S. and Britain Strike a Deal Over a Future Panama Canal

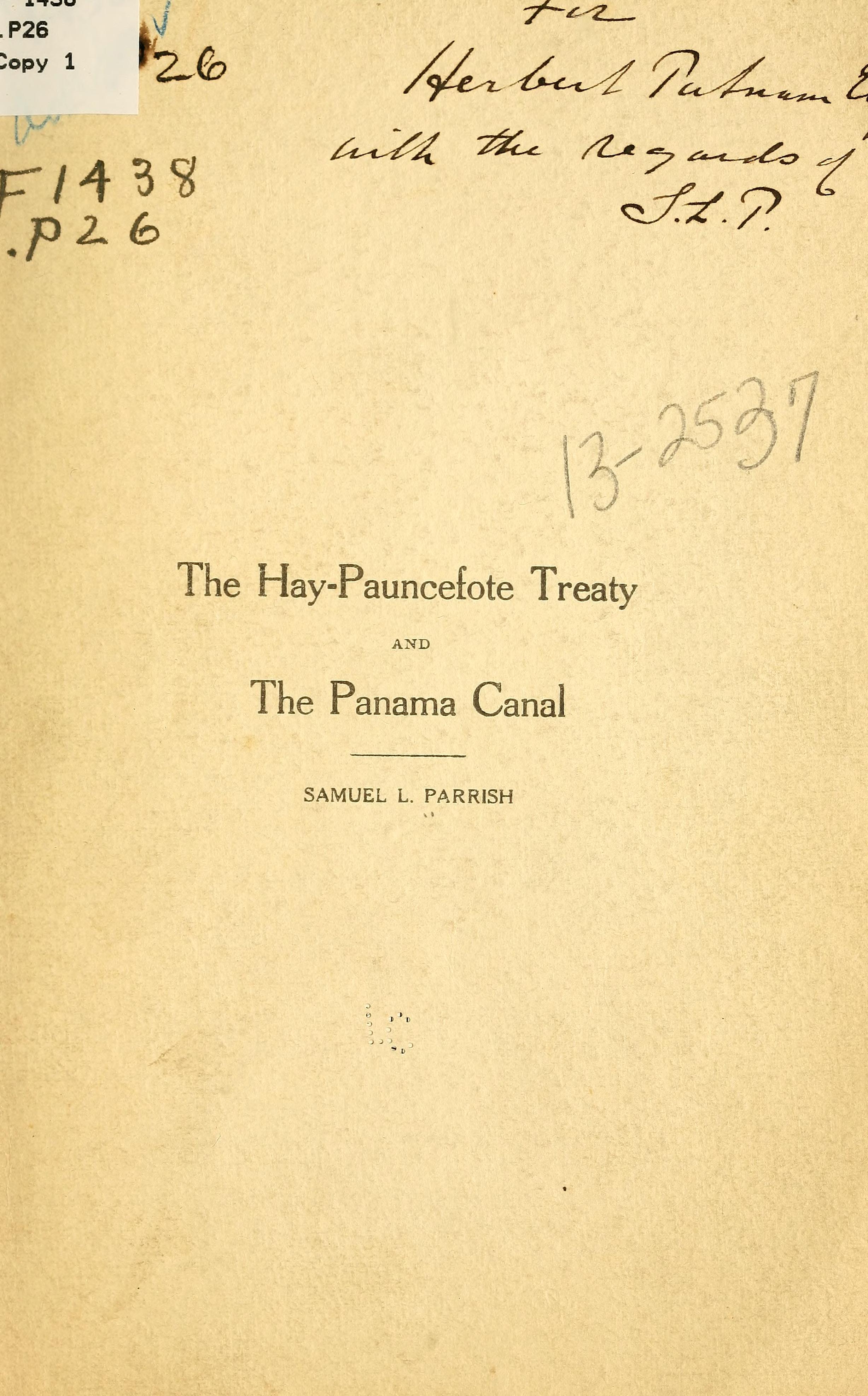

Construction of the Panama Canal, with workers and steam shovels carving through the jungle.

What Happened?

For decades, world powers dreamed of a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific. The journey around Cape Horn was long, treacherous, and costly. The French tried and failed. The British eyed it cautiously. But by 1900, the U.S. saw an opportunity—and took it.

The first Hay-Pauncefote Treaty, signed between U.S. Secretary of State John Hay and British Ambassador Julian Pauncefote, was supposed to be a compromise. It allowed the U.S. to construct an interoceanic canal—ostensibly under terms of neutrality. But neutrality was relative. The U.S. had no intention of merely building a canal; it wanted to control it. When Britain pushed back against American military fortifications along the future canal, the U.S. Senate demanded amendments. Britain rejected them, and the treaty fell apart. A second version, signed in 1901, fully granted the U.S. the right to build and defend a canal without British interference. America had just secured its most significant geopolitical advantage of the 20th century.

But where to dig? Nicaragua was the original favorite—until an inconvenient volcanic eruption sent Congress scrambling for a safer bet. The U.S. turned its eyes to Panama, a province of Colombia, where a failed French canal project had already left behind abandoned infrastructure. The only problem? Colombia wasn’t eager to hand over the land.

Enter Theodore Roosevelt, who had no patience for bureaucratic delays. When Colombia hesitated to sign over rights to the U.S., Roosevelt backed a Panamanian rebellion. With U.S. warships conveniently stationed offshore, Panama declared independence in 1903, and Washington swiftly recognized the new republic. A mere two weeks later, a treaty was signed granting the U.S. full control of the canal zone—for a bargain price.

The construction of the Panama Canal was a marvel of engineering, but it came at a steep human cost. Thousands of workers—many of them West Indian laborers—died from disease and accidents. But by 1914, the dream was realized: a 51-mile lock-and-lake waterway, connecting the world’s oceans and revolutionizing global trade.

For the United States, the canal was more than a trade route—it was a statement of power. American warships could now move swiftly between the Atlantic and Pacific, cementing the country’s role as a dominant military force. But the canal also became a symbol of American interventionism in Latin America. Panama remained under heavy U.S. influence for much of the 20th century, and resentment simmered for decades. By the 1970s, the call for Panamanian sovereignty was deafening. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed a treaty promising to return control of the canal to Panama by 2000. That transition was completed on December 31, 1999, closing a century-long chapter of U.S. control.

The Hay-Pauncefote Treaty was the first domino in a chain reaction of imperial ambition, economic transformation, and political upheaval. The canal itself became a symbol of what the U.S. could accomplish—and what it was willing to do in the name of progress.

Why It Matters

The Panama Canal reshaped the world’s economy, linking oceans and accelerating global trade. But its history is also a cautionary tale of diplomacy, intervention, and exploitation. The U.S. used treaties, rebellions, and military force to secure its vision of progress—often at the expense of the very nations it claimed to be helping. As we navigate modern international relations, the question remains: What are the long-term costs of short-term gains? And who truly benefits when world powers redraw the map?

?

Dig Deeper

Discover what it took to build the Panama Canal, and how this colossal construction project changed the region.

Related

The Louisiana Purchase: A River, A Bargain, and a Bigger United States

In 1803 the United States bought the vast Louisiana Territory from France, doubling the nation’s size, securing the Mississippi River, and setting the stage for westward expansion and hard questions about slavery and Native sovereignty.

Who Was Molly Pitcher? Unpacking the Legend, the Facts, and the Firepower

Was she a single fearless woman, or the name shouted when soldiers needed water? The truth is more complicated—and more powerful. Meet the women behind the legend of Molly Pitcher.

The Conservative Resurgence and Economic Shifts

How a political swing to the right reshaped America’s economy, culture, and political identity in the late 20th century.

Further Reading

Stay curious!