The Fine Print of Dispossession: Congress Ratifies Treaties That Expel Indigenous Nations

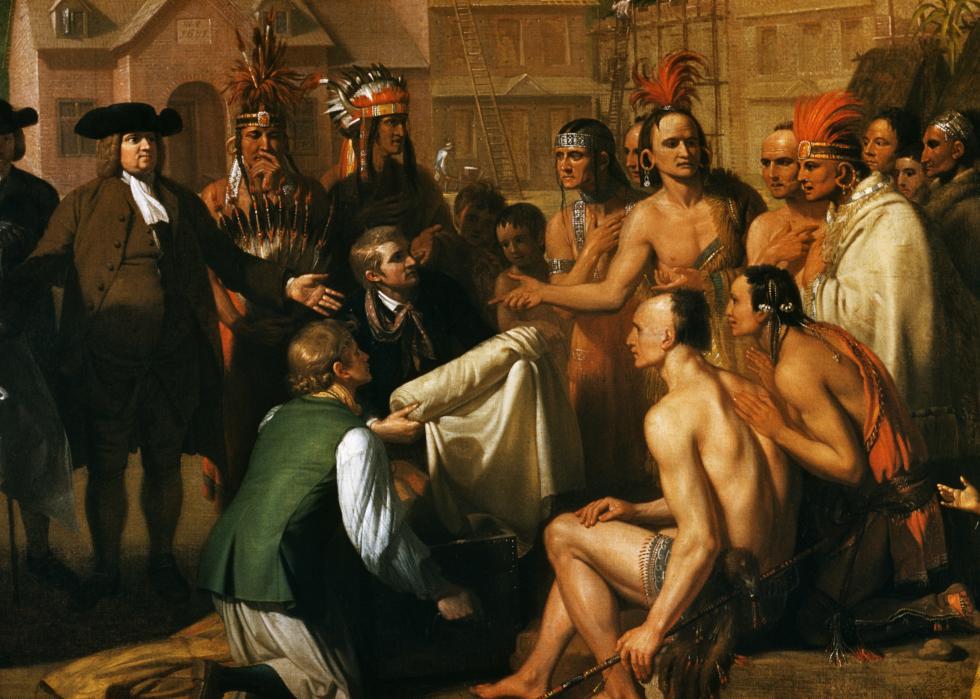

The U.S. government, with its expanding frontier and hunger for land, wielded treaties not as legal agreements between equal nations, but as tools of coercion.

What Happened?

By the early 19th century, U.S. expansion was accelerating, driven by a vision of Manifest Destiny that saw land as a commodity rather than a cultural and spiritual inheritance. Indigenous nations, whose understanding of land ownership differed from European models, found themselves labeled as obstacles to progress rather than sovereign peoples.

Andrew Jackson, a key architect of Indian removal policies, had spent years brokering treaties—none of which genuinely upheld Indigenous rights. His presidency culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which set the legal framework for mass displacement.

The 1837 treaties specifically targeted the Iowa, Sauk, Fox, Oto, Omaha, Missouri, and Sioux nations, stripping them of millions of acres of land in exchange for payments, relocation assistance, and empty promises of protection. Many of these terms were never honored.

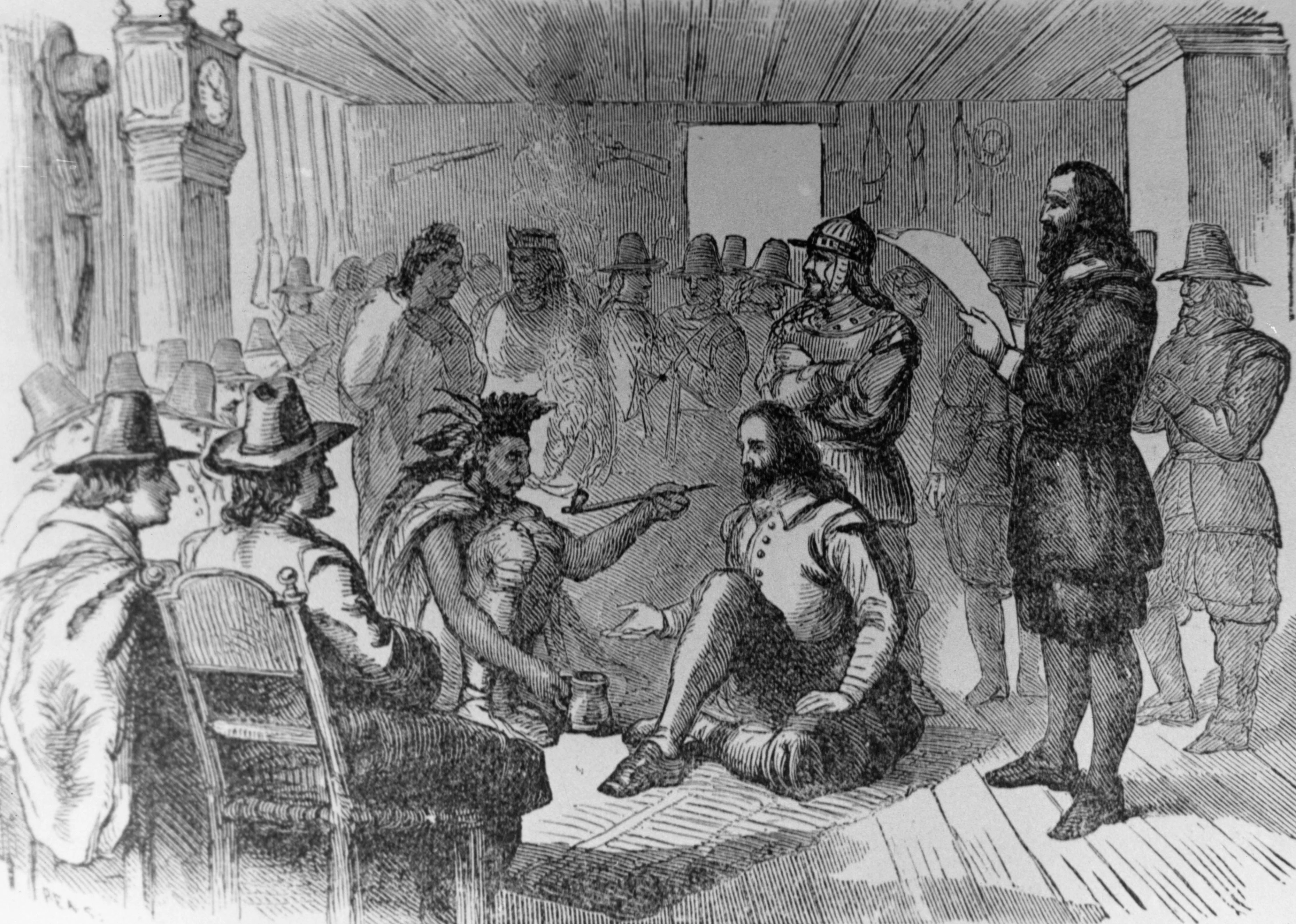

The treaties, like many others, were designed to appear lawful but functioned as instruments of forced removal. Indigenous leaders were often coerced into signing, under the threat of military action or starvation, as settler encroachment had already disrupted their traditional food sources.

The repercussions were immediate and devastating. Within a year, thousands of Indigenous people were forcibly relocated, facing disease, starvation, and exposure along the journey west. This was not just land loss; it was an erasure of culture, language, and self-determination—a legal displacement disguised as diplomacy.

Why It Matters

This was not an isolated event but a deliberate strategy of settler colonialism, codified into law through treaties that were written by one side and rewritten in blood by the other. The U.S. government used the illusion of legal agreements to justify land seizures, systematically disregarding the sovereignty of Indigenous nations. The consequences persist today—land disputes, broken treaty promises, and the continued struggle for Indigenous rights are all rooted in this history. These treaties remind us that laws, no matter how eloquently written, mean little when justice is absent. The question remains: If a contract is signed at gunpoint, is it really a contract at all?

?

How did treaties serve as legal mechanisms for land dispossession rather than genuine agreements?

What parallels exist between 19th-century Indigenous land removals and modern issues of land rights and sovereignty?

How might history have unfolded differently if Indigenous nations had been recognized as equal sovereign entities rather than obstacles to expansion?

How do broken treaties from the 19th century continue to impact Indigenous communities today?

Dig Deeper

The U.S. government made treaties with Indigenous people when it was convenient, and broke these treaties when it was inconvenient. This recurring pattern made it increasingly difficult for Native people to live – and survive – as they once had.

Related

The U.S.-Mexico War

On May 13, 1846, the U.S. Congress declared war on Mexico. Behind the scenes? Land lust, slave politics, and a president with a map in one hand and a match in the other.

North Carolina’s Road to Secession

Why a state known for hesitation became a decisive force in the Confederacy.

The Great Society: Government as a Force for Good

The Great Society wasn’t just a policy agenda, it was a radical vision of what America could be. With sweeping reforms in health care, education, civil rights, immigration, and the environment, President Johnson’s plan aimed to eliminate poverty and racial injustice once and for all.

Further Reading

Stay curious!