Jefferson vs. Burr: The Electoral Tie That Nearly Broke the Republic

After a viciously contested election in 1800, Jefferson and his supposed running mate, Aaron Burr, found themselves in an electoral tie, throwing the final decision to the House of Representatives.

What Happened?

The election of 1800 pitted Thomas Jefferson, champion of agrarian democracy and states’ rights, against incumbent John Adams, a Federalist who favored a strong central government and close ties with Britain. The result? A deeply divided electorate, a media landscape filled with vicious personal attacks (yes, mudslinging politics is as old as the republic), and an unintended constitutional crisis.

Under the original rules of the Electoral College, electors did not differentiate between votes for president and vice president—they simply voted for two candidates, assuming that the intended president would naturally come out on top. Big mistake. Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr both received 73 votes, creating an awkward situation where Burr—who was meant to be vice president—suddenly had an equal claim to the presidency.

Since no candidate won an outright majority, the decision went to the House of Representatives, where each state delegation would cast one vote to determine the next president. Cue weeks of political deadlock, as Federalists—who controlled the outgoing House—refused to back Jefferson, hoping instead to strike a deal with Burr.

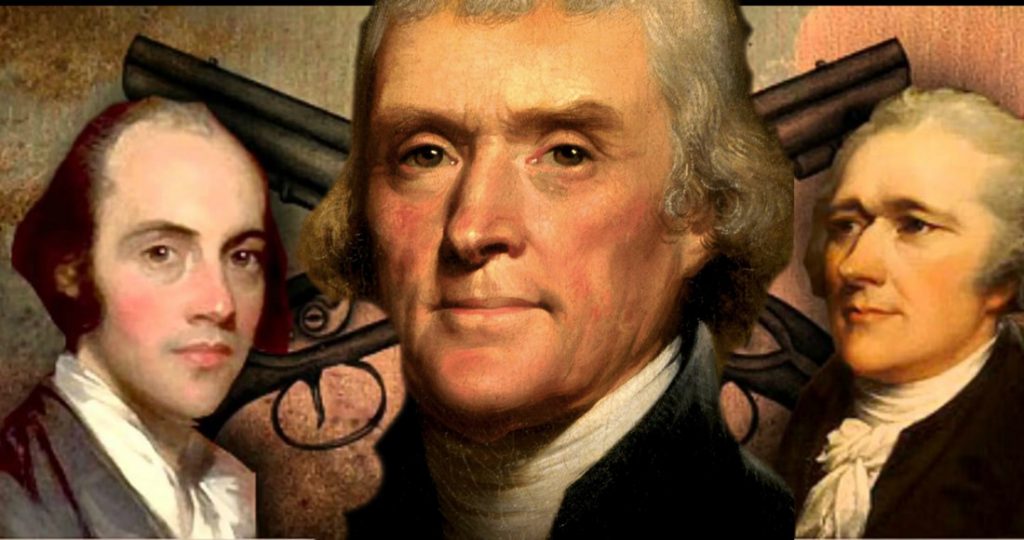

Enter Alexander Hamilton, former Treasury Secretary and Federalist Party puppet master. While he loathed Jefferson’s politics, he despised Burr even more, viewing him as a power-hungry opportunist with no moral compass. Hamilton led a campaign to convince fellow Federalists that Jefferson was the lesser of two evils, arguing that at least Jefferson had principles, whereas Burr was a political wildcard.

After 35 ballots produced the same stalemate, a deal was struck: Federalist representatives in Maryland, Vermont, and Delaware abstained from voting, effectively giving Jefferson the presidency on the 36th ballot. Burr, his ambitions thwarted, was relegated to vice president—a position he’d soon make infamous (spoiler: he kills Hamilton in a duel three years later).

The chaos of the election led to a major constitutional reform: The 12th Amendment was ratified in 1804, ensuring that electors would cast separate votes for president and vice president, preventing a repeat of the Jefferson-Burr debacle.

Why It Matters

The election of 1800 wasn’t just about Jefferson vs. Adams—it was about two competing visions of America. Would the young nation lean toward a strong central government, an industrial economy, and close ties with Britain, as the Federalists wanted? Or would it embrace states' rights, an agrarian society, and a more radical democratic ethos, as Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans championed? With Jefferson’s victory, the Federalists lost their grip on power, ushering in an era of ‘Jeffersonian Democracy’ that would dominate American politics for decades. Even more importantly, this election proved that power could be transferred peacefully, setting a precedent that would define the legitimacy of American democracy. But perhaps the biggest takeaway? Never trust Aaron Burr. Just ask Alexander Hamilton.

?

How did the 12th Amendment change the electoral process after the 1800 election?

What role did Alexander Hamilton play in shaping the outcome of this election?

Why was the election of 1800 called the ‘Revolution of 1800’?

How did the rivalry between Jefferson and Burr influence American politics in the years after the election?

Dig Deeper

efferson is a somewhat controversial figure in American history, largely because he, like pretty much all humans, was a big bundle of contradictions.

Related

Fascism: Power, Propaganda, and the Fall of Democracy

Fascism emerged from the ruins of World War I and found its foothold in fear, nationalism, and economic despair. It promised unity, but delivered control, conformity, and catastrophe.

Free Market Fever: The Deregulation Debate

When is government the problem—and when is it the solution? Deregulation reshaped the U.S. economy, slashing rules and reshuffling power in the name of freedom and efficiency.

The Progressive Era: Reform, Regulation, and the Limits of Change

From breaking up monopolies to marching for women’s votes, the Progressive Era sought to fix America’s problems — but often left some voices out of the conversation.

Further Reading

Stay curious!