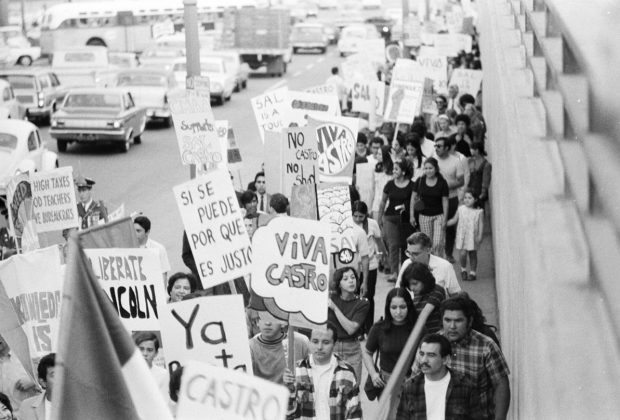

The East L.A. Walkouts: Chicano Students Demand Educational Equality

The East L.A. Walkouts of 1968 were a powerful display of student activism, as thousands of Mexican American students walked out of their high schools to protest overcrowded classrooms, underfunded schools, racist teachers, and a curriculum that erased their history.

What Happened?

By the late 1960s, East Los Angeles schools serving majority-Mexican American students were in crisis. Many were overcrowded, underfunded, and lacking bilingual education or culturally relevant curriculum. Counselors and teachers often discouraged Mexican American students from pursuing higher education, steering them instead toward vocational training or manual labor.

Frustrated by years of neglect and discrimination, students took action. Organizing through underground networks and student groups, they planned mass walkouts beginning in early March 1968. Lincoln High School teacher Sal Castro played a key role in empowering students to stand up for their rights.

The walkouts began on March 1, 1968, at Wilson High School, where students left class to demand better conditions. Over the next five days, students at Roosevelt, Garfield, Lincoln, and Belmont high schools followed suit. Administrators locked doors to prevent them from leaving, and police arrived in riot gear, beating and arresting some of the student protesters.

Despite the crackdown, students held firm. They drafted 39 demands, including an end to racist teachers, the hiring of more Mexican American educators, the introduction of Mexican American history courses, and better school facilities. Though the Los Angeles Board of Education initially agreed with their demands, no meaningful reforms followed.

The movement’s leaders, known as the ‘East L.A. 13,’ were arrested on felony charges of disturbing the peace. Protests erupted in their defense, and by 1970, all charges were dropped. The walkouts inspired other student-led protests and helped shape Chicano activism in the years that followed.

The walkouts were part of a broader Chicano Movement, which sought self-determination, cultural pride, and political power for Mexican Americans. Activists reclaimed the term ‘Chicano,’ turning what was once a racial slur into a badge of pride. They also fought for land rights, labor protections, and increased political representation.

While the walkouts did not immediately fix the inequalities in East L.A. schools, they radicalized a generation of young Chicano activists and educators. Today, the legacy of the 1968 walkouts can be seen in bilingual education programs, Chicano studies courses, and the continued fight for racial justice in schools.

Why It Matters

The East L.A. Walkouts were more than a protest—they were a declaration of dignity, a demand for respect, and a radical act of self-determination. These students refused to accept the status quo and forced the country to recognize the systemic racism embedded in American public education. Their fight for justice still resonates today, as students and activists continue to push for equitable schools, representation, and an education system that reflects the diversity of its students.

?

Dig Deeper

A massive protest by Mexican American high school students was a milestone in a movement for Chicano rights.

Related

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Indigenous Roots of American Democracy

Long before the Founding Fathers gathered in Philadelphia, a league of Native Nations had already established one of the world’s oldest participatory democracies—an Indigenous blueprint for unity, peace, and governance.

Jim Crow and Plessy v. Ferguson

After Reconstruction, the South built a legal system to enforce racial segregation and strip African Americans of political power. The Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 made 'separate but equal' the law of the land—cementing injustice for decades.

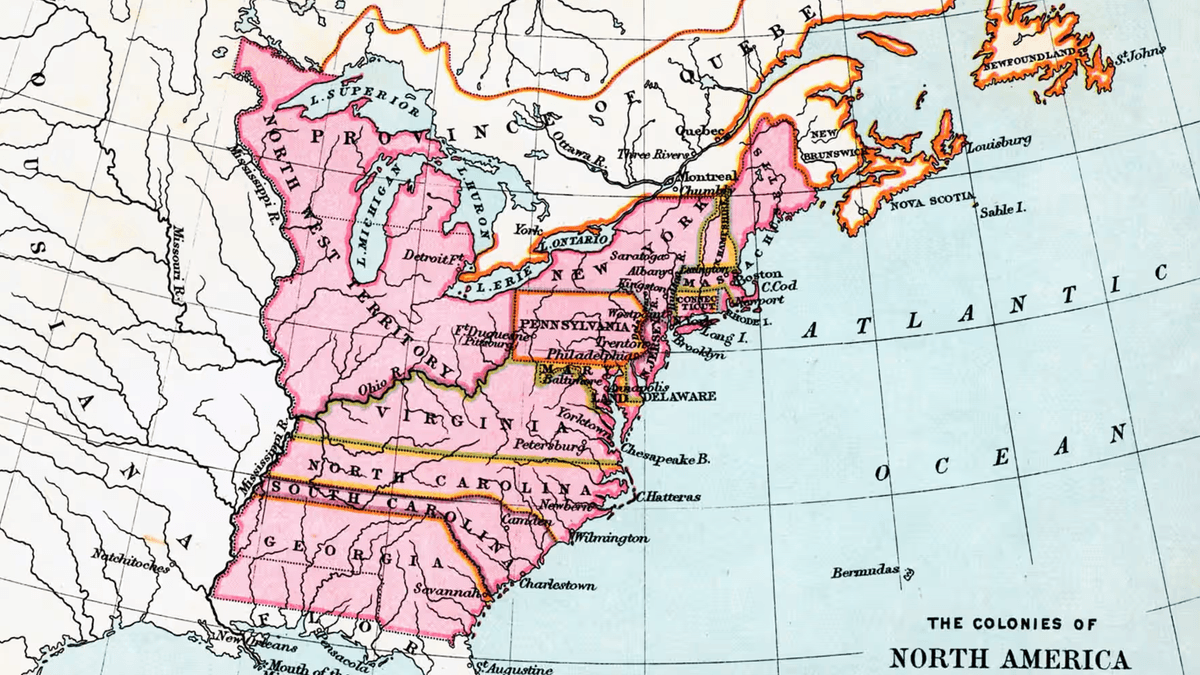

The 13 Colonies: Seeds of a New Nation

How did thirteen scattered colonies along the Atlantic coast grow into the foundation of a new nation?

Further Reading

Stay curious!