The Provincial Freeman Debuts: A Bold Black Feminist Newspaper Ahead of Its Time

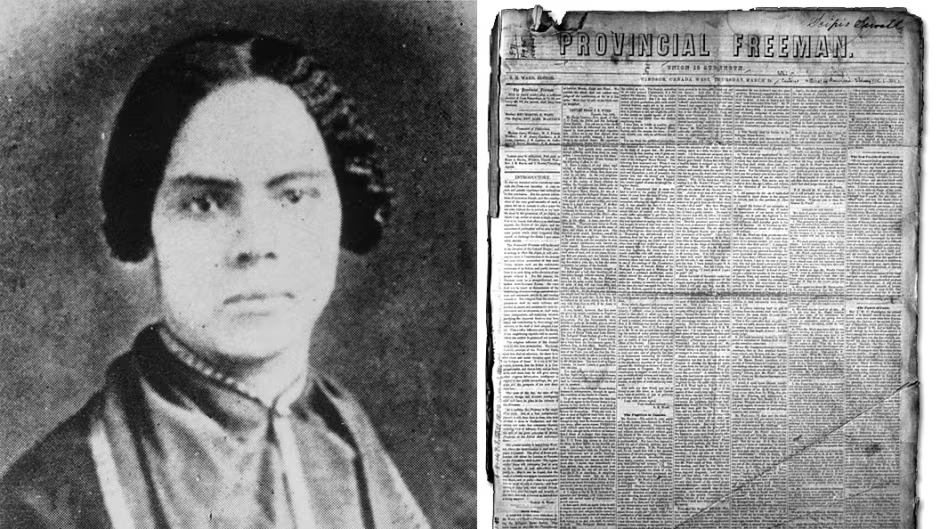

The Provincial Freeman was more than a newspaper—it was a revolution in print. Its co-editor Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first Black woman publisher in North America, used its pages to challenge slavery, racism, and gender norms.

What Happened?

The Provincial Freeman debuted on March 24, 1853, in Windsor, Ontario—a city that had become a haven for thousands of escaped enslaved people fleeing the brutality of the U.S. Fugitive Slave Act. Edited by abolitionist Samuel Ringgold Ward and Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the paper stood unapologetically for Black freedom, integration, and self-education.

Although the masthead never listed her full name, Shadd Cary was the paper’s driving force. She published under initials to hide her gender and protect her voice in a time when Black women were actively silenced. Despite opposition—even from peers like Frederick Douglass—Shadd Cary doubled down on dissent, publishing political critiques, abolitionist calls to action, and reflections on Black women’s lives.

Unlike other abolitionist papers of the time, The Provincial Freeman did not water down its message. Its tone was rebellious and direct, offering blistering critiques of white America, advocating for desegregated schools, and calling out anyone—Black or white—who made excuses for injustice. It documented mutual aid networks, community building efforts, and celebrations of Black academic achievement, like Emaline Shadd’s first-prize graduation from Toronto’s Normal School.

Its editors hoped to reach 40,000 Black Canadians—freedmen, fugitives, and settlers—and build a vision of a new society where Black people could thrive as equals. The Freeman was printed first in Windsor, then Toronto, and finally in Chatham, Ontario before closing in 1857 due to financial strain and political backlash.

The Freeman’s legacy endures because of Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s vision. Her work didn’t end when the press shut down—she became one of the first women to earn a law degree in the U.S., continued organizing during the Civil War, and sued Howard University for gender discrimination. Her words still echo today in every act of resistance that starts with speaking out.

Why It Matters

The Provincial Freeman was a newspaper, but also a megaphone. It amplified the voices of Black Canadians, abolitionist organizers, and women fighting for their place in public life. It reminds us that radical journalism has always been part of liberation work—that publishing can be protest, and editors can be revolutionaries. Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s legacy challenges us to think critically, write boldly, and refuse silence in the face of injustice.

?

Why do you think Mary Ann Shadd Cary chose to hide her identity on the masthead of The Provincial Freeman? What risks might she have faced?

How can newspapers and media today learn from the legacy of The Provincial Freeman?

What role did Black women play in abolitionist organizing that often goes unrecognized in traditional history books?

What does it mean to use publishing or writing as a form of resistance?

Why is it important to preserve the stories of newspapers like The Provincial Freeman today?

Dig Deeper

Shannon Prince, Curator of the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum, tells us about Mary Ann Shadd Cary's legacy and incredible accomplishments, including being the first Black woman publisher in North America and the first woman publisher in Canada.

Related

Jim Crow and Plessy v. Ferguson

After Reconstruction, the South built a legal system to enforce racial segregation and strip African Americans of political power. The Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 made 'separate but equal' the law of the land—cementing injustice for decades.

Votes for Women: The Fight for the 19th Amendment

It took more than 70 years of protests, petitions, and picket lines to win the right for women to vote in the United States. The 19th Amendment didn’t just expand democracy—it redefined it.

Early Industry and Economic Expansion (1800–1850)

From gold mines in North Carolina to textile mills and telegraphs, discover how the Market Revolution transformed the way Americans lived, worked, and connected in the early 19th century.

Further Reading

Stay curious!