The Great Moon Hoax Captivates Readers

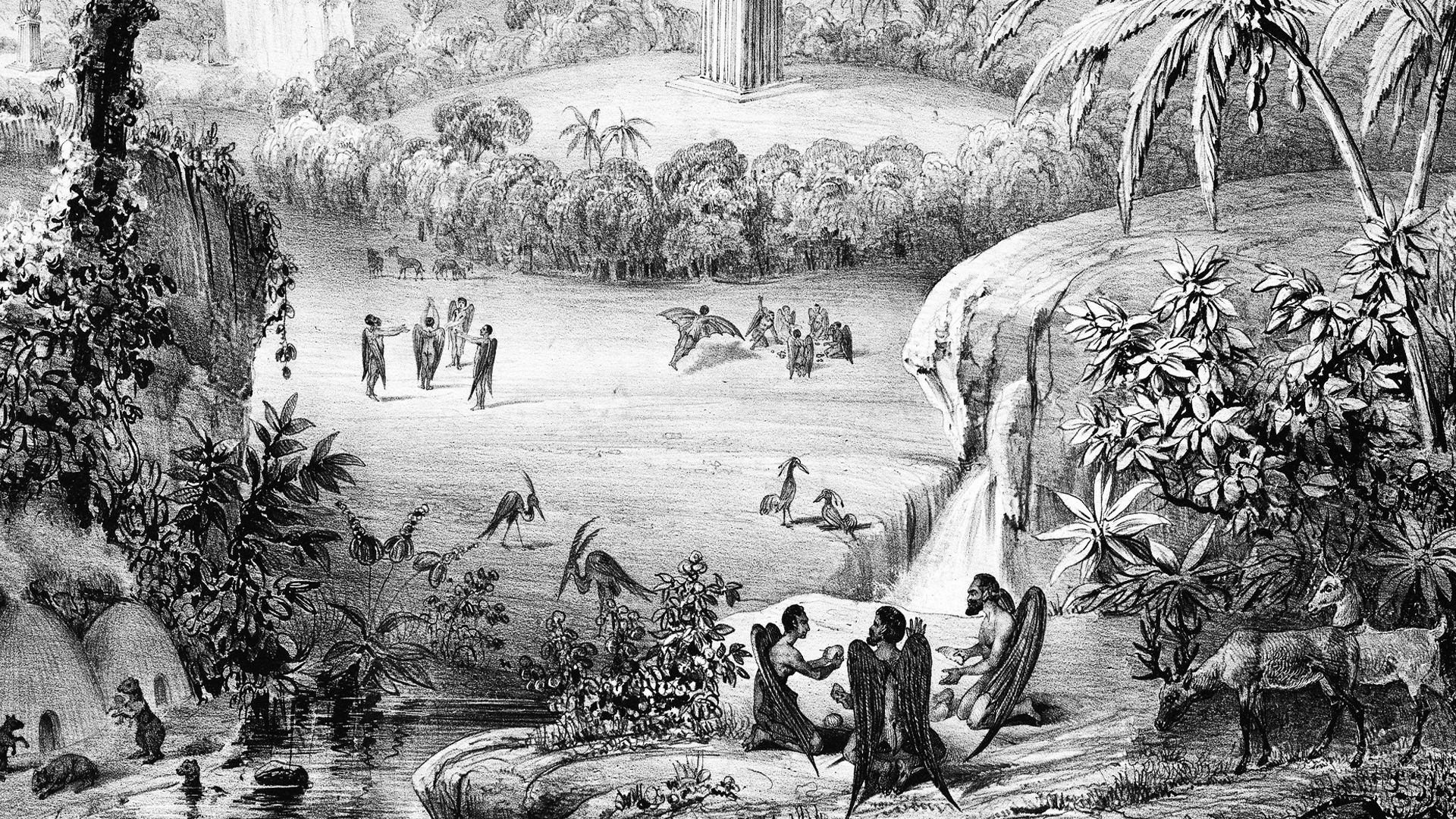

Illustration from the New York Sun’s 1835 series describing imagined creatures on the moon.

What Happened?

On August 25, 1835, the first installment of the 'Great Moon Hoax' appeared in the New York Sun, claiming that astronomer Sir John Herschel had discovered exotic life on the moon using a powerful telescope in South Africa. The articles—supposedly reprinted from the Edinburgh Journal of Science—described lunar unicorns, two-legged beavers, sapphire cliffs, and furry winged humanoids.

In reality, the Edinburgh Journal had ceased publication years earlier, and the byline 'Dr. Andrew Grant' was fictional. The most likely author was Richard Adams Locke, a Sun reporter who intended the story as satire aimed at popular writers who speculated wildly about extraterrestrial life, like Reverend Thomas Dick. Yet readers didn’t see the joke. Sales skyrocketed as the public marveled at the 'discoveries,' and even a Yale University committee traveled to investigate.

The hoax ran for six installments before the Sun admitted the truth on September 16, 1835. Far from damaging the paper, the stunt cemented its place as a pioneer of the 'penny press,' proving that sensational stories could drive mass circulation. Edgar Allan Poe, whose own lunar satire had failed just months earlier, accused Locke of stealing his idea.

The Great Moon Hoax stands as an early example of how misinformation thrives when it is packaged in the familiar language of science and journalism. Just as in today’s digital media landscape, fact and fiction blurred, sparking debates, jokes, and even further hoaxes. The tale reminds us that the human appetite for wonder often outpaces our willingness to question what we read.

Why It Matters

The Great Moon Hoax is more than a quirky footnote—it foreshadowed the ongoing struggle between truth and misinformation in mass media. It showed how quickly a false but fascinating story could capture the public imagination, sell papers, and even fool scientists. In an era of viral posts and conspiracy theories, the 1835 hoax is a reminder that media literacy isn’t just modern homework; it’s been the people’s task for nearly two centuries.

?

Why did readers in 1835 believe the Moon Hoax despite its absurd claims?

How did the 'penny press' change American journalism?

What role did satire play in the creation of the Moon Hoax?

How does the Great Moon Hoax compare to misinformation spread through today’s social media?

Why did Edgar Allan Poe believe his own story idea had been stolen by the Sun?

Dig Deeper

In August 1835, a New York newspaper stunned the world with reports of life on the moon. From unicorns to bat-people, the hoax became one of history’s most famous cases of media misinformation.

Dive into the phenomenon known as circular reporting and how it contributes to the spread of false news and misinformation.

How do facts become misconceptions? This video explores the psychology of misinformation and why humans are vulnerable to believing hoaxes.

Related

McCarthyism: Fear, Power, and the Red Scare

In the 1950s, fear of communism gripped America. Senator Joseph McCarthy fueled this fear by accusing hundreds of people of being communist traitors—often without proof. The result was a national panic that tested the meaning of truth, justice, and freedom.

How to Spot Misinformation

Misinformation is the lie that dresses like the truth—and learning to spot it is a civic survival skill.

The Role of Social Media in Shaping Public Opinion

Social media is a powerful tool that influences public opinion on a global scale, but its impact isn't always positive. What does it mean for democracy, and how can we address the challenges of misinformation and echo chambers?

Further Reading

Stay curious!