Phillis Wheatley’s Groundbreaking Debut

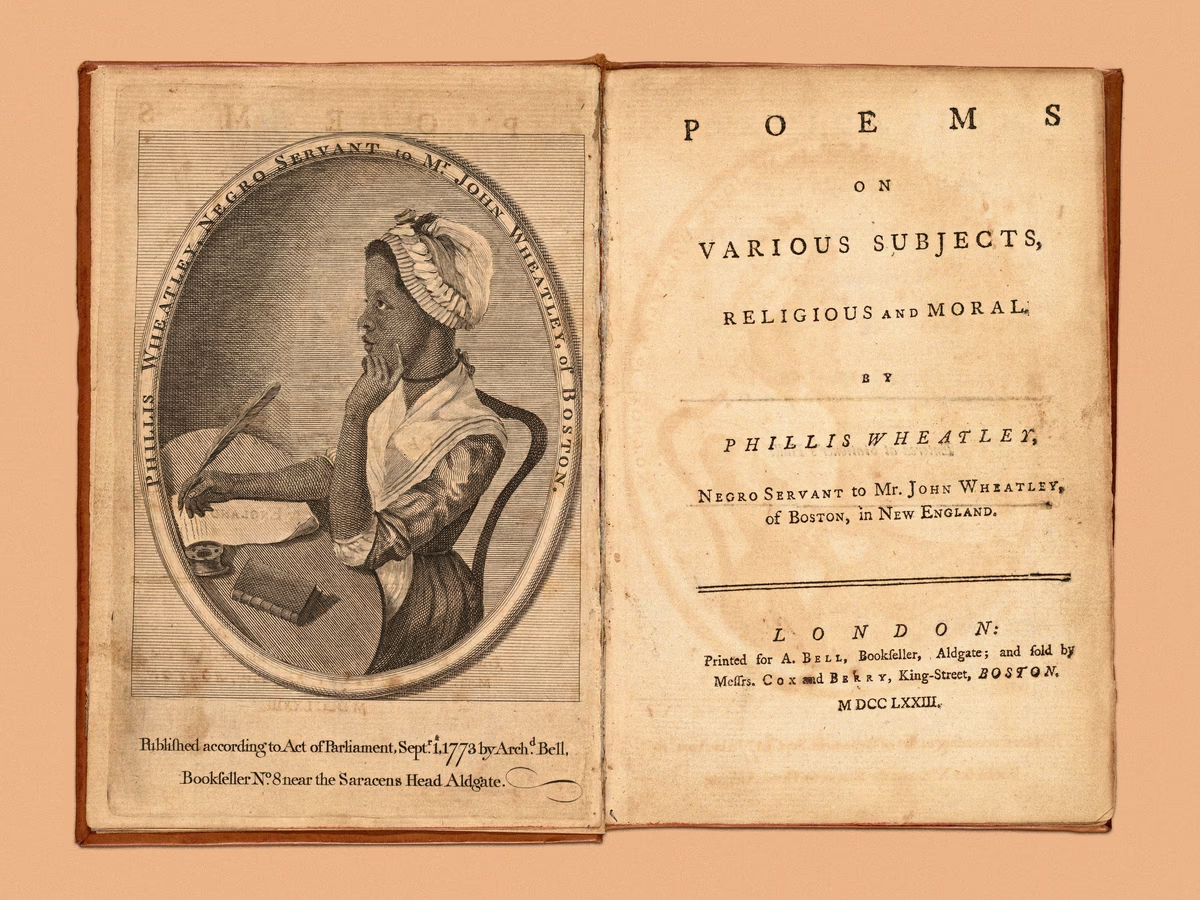

Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral made her the first Black woman—and first enslaved American—to publish a book of poetry.

What Happened?

In 1773, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in London—the first known book of poetry published by a Black woman, and the first by an enslaved American. Its existence was a revelation. In an age that denied people of African descent their humanity, let alone their intellect, Phillis Wheatley’s voice broke through with verses that were elegant, learned, and unmistakably her own.

Born in the Senegambia region of West Africa, Wheatley was kidnapped as a child and sold into slavery in Boston in 1761. Purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, she was named for the ship that carried her across the Atlantic. Unlike most enslaved children, Phillis was educated by the Wheatleys, learning to read and write English, mastering Latin and the Bible, and absorbing the classics. By her early teens she was composing poetry; at seventeen she saw her first poem in print.

Colonial Boston, however, would not support her ambition to publish a book. Undeterred, Wheatley traveled to London in 1773 with Nathaniel Wheatley, where she found an audience eager for her work. With the patronage of Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, her collection was published. Its thirty-nine poems ranged from neoclassical odes to meditations on faith, freedom, and the paradox of Christian colonists defending liberty while sustaining slavery.

The book’s impact reverberated across Britain and the colonies. Wheatley’s art was undeniable proof of Black intellect and creativity, arming abolitionists with evidence against the myth of racial inferiority. Her poem On Being Brought from Africa to America made her own captivity the subject of reflection, embedding the moral contradictions of slavery within the very language of faith her society claimed to honor.

Though freed shortly after publication, Wheatley’s life was shadowed by poverty, loss, and the harsh realities of a world unprepared to support a free Black woman writer. She continued to write, corresponded with figures like George Washington, and produced works that have since been rediscovered. She died in 1784 at only thirty-one, leaving behind one published volume—but one that shifted the literary and political landscape.

Wheatley’s achievement was more than personal triumph. It marked a foundational moment in African American letters and in the global struggle for freedom. Her book became both a weapon for abolitionists and a seed for future generations of Black writers, a reminder that genius endures even when born in chains.

Why It Matters

Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 collection was more than a literary milestone—it was a direct challenge to a world built on racial hierarchy. By mastering the dominant culture’s language and forms, she proved that genius could not be confined by skin color or chains. Her book gave abolitionists evidence to dismantle the lie of Black inferiority, offered future writers a lineage to inherit, and widened the very definition of who could claim the title of poet in the Atlantic world.

?

How did patronage and the Countess of Huntingdon’s support make Wheatley’s publication possible?

In what ways do Wheatley’s classical and religious references advance an argument against slavery?

Why did colonial subscribers initially resist funding Wheatley’s book, and what changed in London?

How did Wheatley’s work influence abolitionist discourse in Britain and America?

What newly discovered poems have reshaped our understanding of Wheatley’s life and art?

Dig Deeper

A concise portrait of Wheatley’s life, publication, and Revolutionary-era connections, including her correspondence with George Washington.

How Wheatley’s literacy and poetry challenged colonial racism and helped reshape public perceptions of Black intellect.

An exploration of Wheatley’s rise, her later struggles, and the recovery of her legacy.

Related

The Encomienda System: Empire, Labor, and the Roots of Colonial Slavery

The encomienda system promised 'protection' and Christianization. What it delivered was forced labor, cultural erasure, and the blueprint for slavery in the Americas.

The Emancipation Proclamation & The 13th Amendment

Freedom on paper is one thing; freedom in practice is another. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were giant leaps toward liberty—yet the road ahead for formerly enslaved people was long and uneven.

Human Rights

Human rights are the basic freedoms and protections that belong to every person on Earth. They help keep people safe, ensure dignity, and make freedom, justice, and peace possible. But these rights aren’t just given—they must be understood, protected, and defended by all of us.

Further Reading

Stay curious!