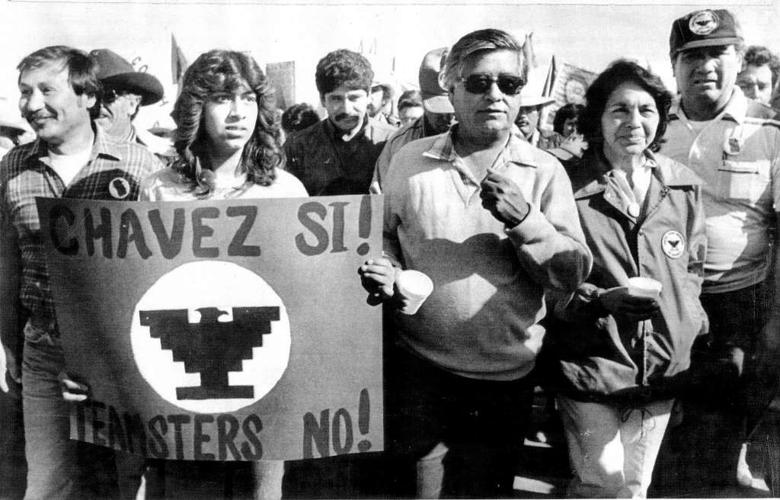

Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta Found the National Farm Workers Association

Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta speaking to farmworkers under the black eagle flag of the NFWA.

What Happened?

For decades, farmworkers had picked fruits and vegetables that ended up on America’s tables while living in poverty themselves. They often worked long hours under the hot sun for very little pay, lived in poor housing, and faced discrimination if they tried to speak up. Farm owners replaced anyone who protested with new laborers, making it nearly impossible to fight for change.

Cesar Chavez, who had already been organizing voter registration drives and campaigns against discrimination, believed farmworkers needed their own organization. Dolores Huerta, a talented negotiator who had worked with Filipino labor leaders, joined him. Together they launched the NFWA in Delano, California, using the symbol of a black Aztec eagle on a red flag to unite workers.

At first, building the movement was slow. Chavez went door-to-door, holding small meetings in homes and churches, asking workers to contribute $3.50 a month in dues. It was a sacrifice for families barely getting by, but it gave them a sense of ownership and pride in their union. Members gained access to funeral insurance, credit unions, and the feeling that they finally mattered.

In 1965, the NFWA partnered with Larry Itliong and Filipino workers in a strike against grape growers who refused to raise wages above $1 an hour. The strike grew to thousands of workers across dozens of vineyards. When growers brought in replacement workers, Chavez and Huerta called for a nationwide grape boycott. Millions of consumers across the U.S. stopped buying grapes until workers were treated fairly.

This boycott, supported by civil rights activists and religious groups, transformed a local labor struggle into a national movement. It showed how ordinary people, even those far from California, could stand in solidarity with farmworkers simply by changing their shopping habits. The slogan 'Sí se puede' ('Yes we can') captured the spirit of determination and hope.

The grape strike lasted five years and ended in 1970, when over 30 growers signed contracts with the NFWA, guaranteeing better pay and safer conditions. The NFWA soon became part of the United Farm Workers (UFW), a union that carried the struggle forward for decades. Dolores Huerta, who negotiated thousands of contracts, and Cesar Chavez, who later fasted to protest pesticide use, became national icons for justice.

The NFWA’s story connects to the larger Civil Rights Movement. Just as African Americans fought for equality in schools, housing, and jobs, Mexican American and Filipino workers fought for fairness in the fields. Both struggles relied on nonviolence, community organizing, and the courage of ordinary people willing to risk everything for dignity.

The legacy of the NFWA reminds us that civil rights aren’t just about laws passed in Washington—they’re also about the food on our tables, the clothes we wear, and the people who labor behind the scenes. Chavez and Huerta proved that even the most marginalized voices can shape history when they stand together.

Why It Matters

The founding of the NFWA was a turning point for American labor and civil rights. By organizing farmworkers into a union, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta showed the power of solidarity and nonviolent protest. Their boycotts and strikes connected rural struggles to national conversations about justice, proving that even the most marginalized voices could reshape laws, labor practices, and public consciousness. The NFWA laid the foundation for the United Farm Workers and inspired future generations to keep fighting for justice in the workplace.

?

Why did Chavez and Huerta believe farmworkers needed their own union?

How did the grape boycott turn a local labor struggle into a national movement?

What does the slogan 'Sí se puede' mean, and why do you think it was so powerful?

How did the struggles of farmworkers connect to the larger Civil Rights Movement?

What lessons can today’s workers and activists learn from the NFWA?

Dig Deeper

Learn how Cesar Chavez grew from migrant farmworker to national civil rights leader through strikes and boycotts.

Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the NFWA, worked tirelessly to secure rights for agricultural laborers.

Related

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Enforcing the 15th Amendment

How a landmark law transformed voting access in the South and gave real force to the promises of the 15th Amendment.

Universal Suffrage in the United States

The right to vote wasn’t handed to everyone—it was fought for, over centuries, by people demanding that democracy actually mean everyone has a voice.

MLK the Disrupter and the Poor People’s Campaign

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final chapter was about more than civil rights—it was a bold demand for economic justice that challenged the nation’s values at their core.

Further Reading

Stay curious!