The First National Women’s Rights Convention

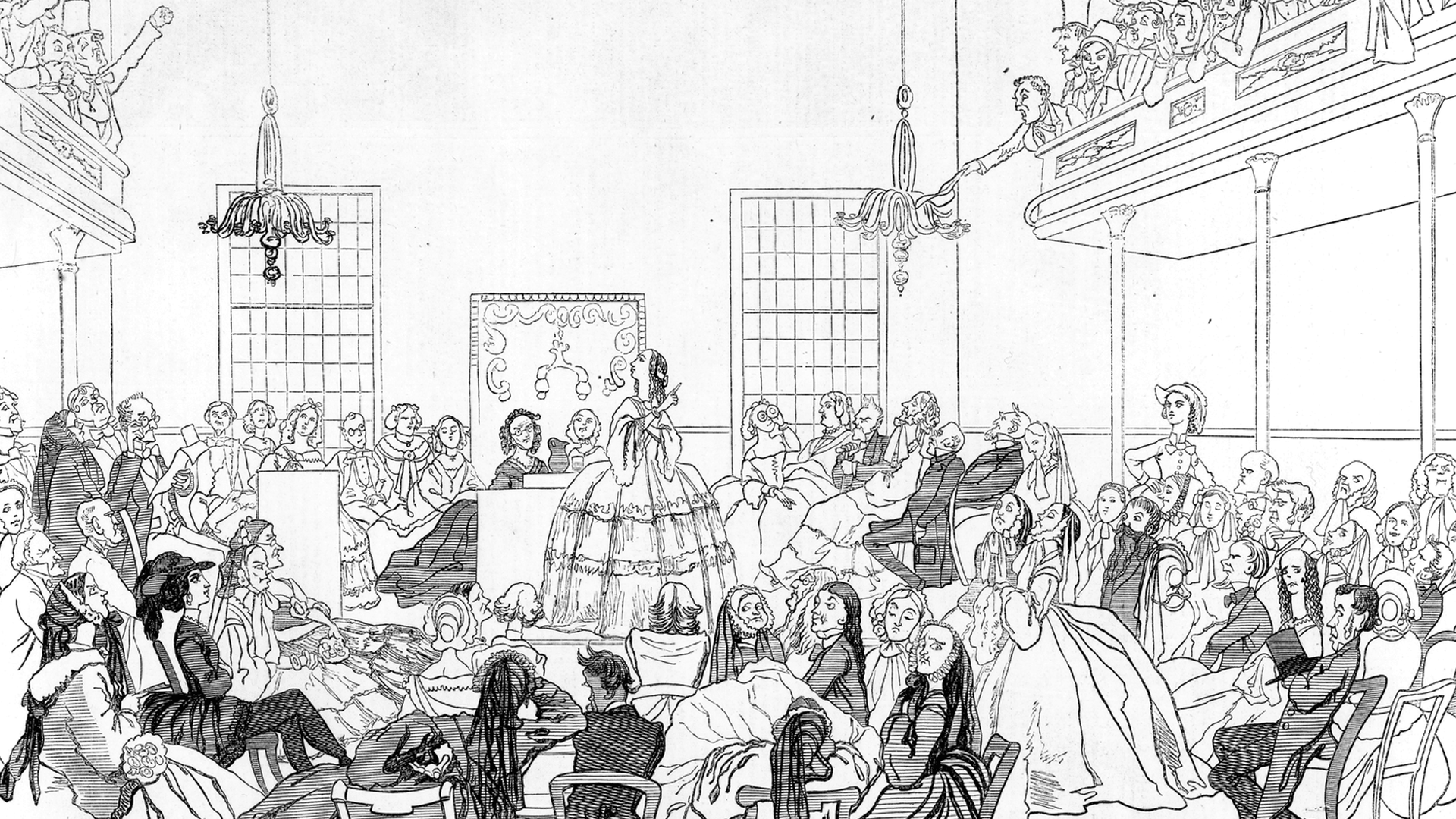

Illustration of the 1850 National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, showing women and men gathered in Brinley Hall.

What Happened?

In the mid-1800s, American women had few legal rights. Married women couldn’t own property, control their wages, or sign contracts. They couldn’t vote, hold office, or attend most colleges. Many reformers, especially those active in the anti-slavery movement, saw these injustices as linked to broader systems of oppression and began calling for change.

Two years earlier, the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York had issued a Declaration of Sentiments that boldly declared, 'All men and women are created equal.' But in 1850, activists wanted to move from words to action. They organized a national convention to unite women’s rights supporters from across the country under a shared plan for reform.

On October 23, 1850, over 1,000 delegates—men and women—met at Brinley Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts. Planned by members of the Anti-Slavery Society, including Lucy Stone, Paulina Wright Davis, and Abby Kelley Foster, the convention was a powerful blend of the abolition and women’s rights movements. The meeting aimed to create a national organization and a clear political strategy to win women equal rights under the law.

Lucy Stone emerged as one of the event’s most memorable speakers. She demanded that women be free to live as full human beings, not as extensions of their husbands or fathers. 'We want that when she dies, it may not be written on her gravestone that she was the wife of somebody,' Stone declared, a radical statement in a society where women’s identities were legally tied to men.

Other speakers included Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Lucretia Mott. Their presence emphasized how the fight for women’s equality was intertwined with the fight against slavery and racial injustice. Truth, a formerly enslaved woman, challenged both racism and sexism, insisting that freedom must include everyone.

The press reacted with ridicule. Some newspapers mocked the women’s clothing and ideas, calling the convention 'an awful combination of socialism, abolitionism, and infidelity.' But that attention spread the message far beyond Worcester. Transcripts of the speeches were printed and sold as pamphlets, inspiring readers across the U.S. and even in Europe.

The Worcester convention marked a turning point. From then on, annual national meetings were held to discuss women’s rights, producing networks, newspapers, and reform organizations that strengthened the suffrage cause. Activists began pushing not only for voting rights but also for fair pay, better education, and an end to unjust marriage laws.

The movement wasn’t perfect. Later disagreements over race and voting split the suffrage movement after the Civil War, revealing deep divisions about who should be included in the struggle for equality. Still, the 1850 convention set a precedent for national organizing and proved that women’s rights were not a fringe issue, they were central to the nation’s democratic promise.

Looking back, the convention’s legacy reminds us that real progress takes time, courage, and coalition-building. The speeches delivered in Worcester in 1850 echoed through the decades that followed, helping to build the foundation for the eventual ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which granted women the right to vote.

Why It Matters

The first National Women’s Rights Convention was a milestone in turning women’s equality from an idea into a movement. It connected local reformers across states, united the causes of women’s rights and abolition, and gave new leaders like Lucy Stone and Sojourner Truth a national stage. Though progress was slow and uneven, the convention helped set the agenda for generations of activism that would transform American democracy.

?

How did the first National Women’s Rights Convention build on the work begun at Seneca Falls?

Why were both men and women important to the early women’s rights movement?

What risks did activists like Lucy Stone and Sojourner Truth face for speaking publicly about equality?

Why did the press mock the convention, and how did that actually help spread its message?

How did this early movement lay the groundwork for the eventual passage of the 19th Amendment?

Dig Deeper

A look at how decades of activism—from the first conventions to the final vote—won women the right to vote in 1920.

Related

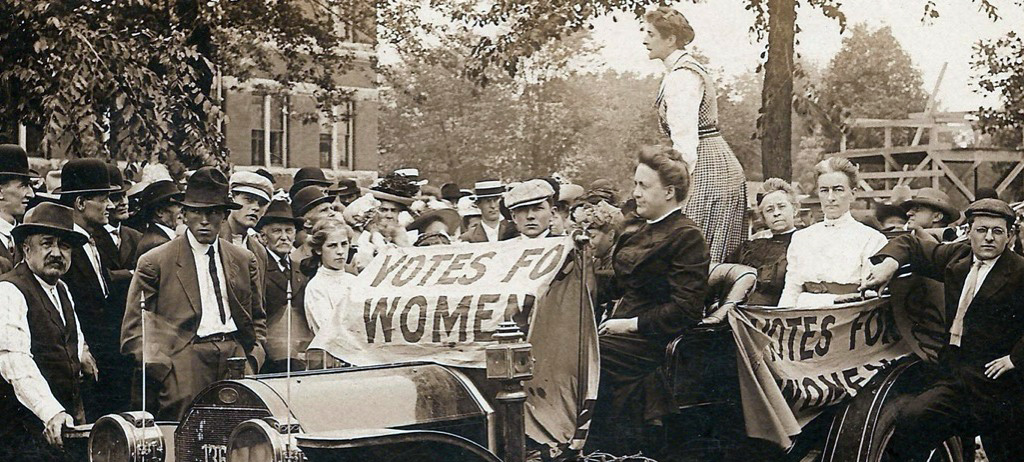

Votes for Women: The Fight for the 19th Amendment

It took more than 70 years of protests, petitions, and picket lines to win the right for women to vote in the United States. The 19th Amendment didn’t just expand democracy—it redefined it.

Basic Rights and Personal Responsibilities

Rights give us freedom. Responsibilities protect those freedoms—for ourselves and for each other.

The Emancipation Proclamation & The 13th Amendment

Freedom on paper is one thing; freedom in practice is another. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were giant leaps toward liberty—yet the road ahead for formerly enslaved people was long and uneven.

Further Reading

Stay curious!