The New York Committee of Vigilance is Founded

The New York Committee of Vigilance formed in response to the terrifying reality that even in a free state, Black New Yorkers were never truly safe.

What Happened?

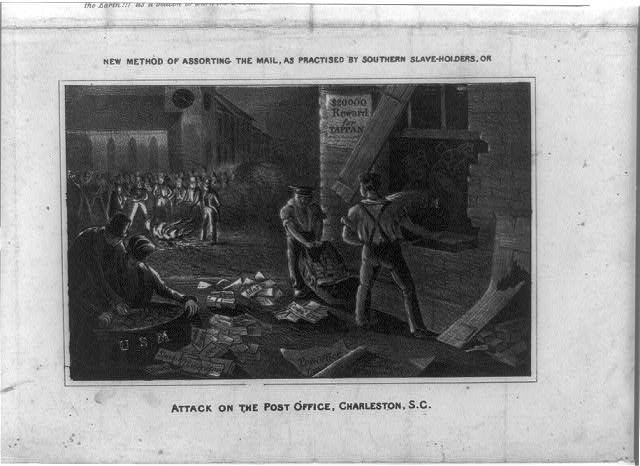

In 1827, New York State officially ended slavery, but life for Black New Yorkers remained extremely dangerous. Kidnappers, corrupt police, and hired bounty hunters roamed the city looking for Black men, women, and children to seize and sell into slavery. With the support of wealthy merchants and politicians tied to the Southern cotton trade, these “kidnapping clubs” operated freely, often arresting people without evidence and sending them south before their families could even locate them.

On November 20, 1835, David Ruggles—a young, free Black abolitionist—founded the New York Committee of Vigilance (NYCV) to confront this injustice directly. Ruggles believed that abolition required more than speeches; it required bold, immediate action to protect people whose freedom was under threat. The committee united Black and white New Yorkers in a mission to defend free Black residents and assist enslaved people escaping to the North.

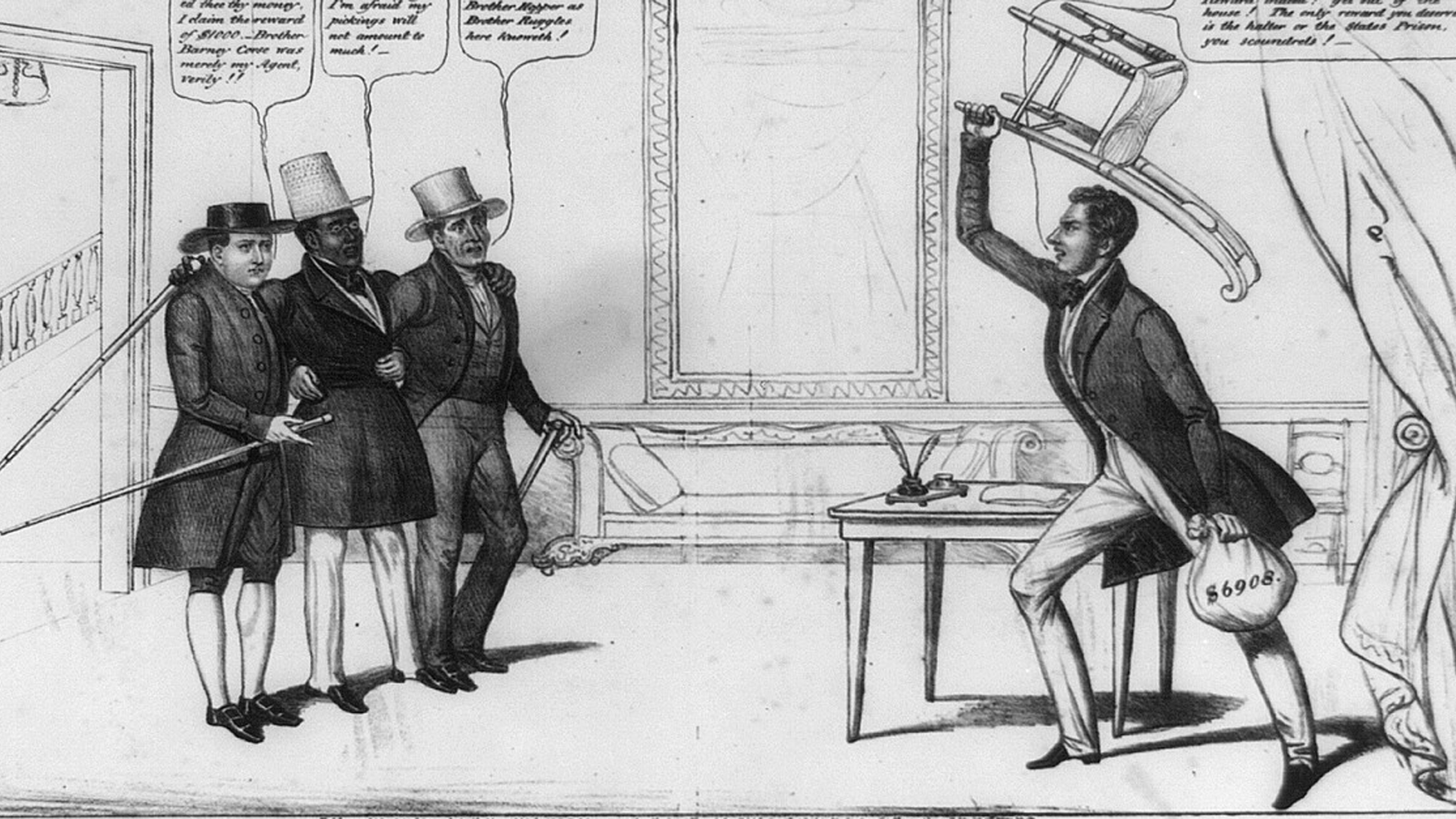

NYCV members boarded ships arriving in New York Harbor, searching for kidnapped Black captives or illegally enslaved people brought into the city. When they found victims, they worked to free them, sometimes physically intervening to stop slave catchers. They demanded jury trials for anyone accused of being a fugitive, raised funds for legal defense, and built a network of homes, churches, and safe rooms that became crucial stops on the Underground Railroad.

Behind the scenes, the committee relied on countless unnamed Black New Yorkers: domestic workers who overheard suspicious conversations, dockworkers who spotted captives on ships, women who cooked meals for fugitives, and neighbors who offered shelter at great personal risk. Though many were poor and had little to give, they donated money, food, clothing, and time to the movement.

One of the most famous people helped by the Committee of Vigilance was Frederick Douglass, who arrived in New York in 1838 as a young fugitive. He described arriving in the city alone, terrified that slave catchers could capture him at any moment. Ruggles welcomed him, sheltered him, connected him to allies, and helped him travel safely to New Bedford, where Douglass began his rise to national fame.

The NYCV faced constant danger from slave catchers, hostile politicians, and violent mobs. Many white New Yorkers supported slavery because their wealth depended on Southern cotton, and Black abolitionists were often targeted for beatings, arrests, and threats. Ruggles himself survived arson attacks, assaults, and repeated arrests. His health eventually collapsed, forcing him to leave the city, but his work sparked the creation of Vigilance Committees in Philadelphia, Boston, Rochester, Cleveland, Detroit, and more.

By 1838, the NYCV reported saving more than 500 people from being enslaved. They exposed kidnappers, fought corrupt judges, and protected families who might otherwise have been torn apart forever. Their work helped build the foundation of the Underground Railroad and taught future generations of activists the power of community defense and organized resistance.

Although their story was overshadowed by later abolitionist heroes, the New York Committee of Vigilance showed that everyday people—teachers, sailors, mothers, church members, business owners—could resist injustice by standing together, sharing information, and refusing to let their neighbors be stolen away. Their bravery continues to inspire movements for justice today.

Why It Matters

The New York Committee of Vigilance proved that freedom isn't just a law—it must be actively protected. Their work shows how communities can resist injustice when formal systems fail and how ordinary people can save lives by staying informed, speaking up, and standing together. Understanding their courage helps us see how grassroots action can challenge racism, protect vulnerable people, and build pathways toward justice even in the most dangerous times.

?

Why did kidnappers target Black New Yorkers even after slavery was abolished in the state?

What made David Ruggles’ approach to abolition different from many others?

How did everyday community members help the New York Committee of Vigilance?

Why was New York City especially dangerous for escaped enslaved people?

What lessons does the Committee of Vigilance teach us about standing up to injustice?

Dig Deeper

David Ruggles, his activism, and his role in protecting fugitive enslaved people.

Related

The Emancipation Proclamation & The 13th Amendment

Freedom on paper is one thing; freedom in practice is another. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were giant leaps toward liberty—yet the road ahead for formerly enslaved people was long and uneven.

From Articles to the Constitution

The Articles of Confederation got us through a revolution—but not much more. Weak laws, no executive, and constant in-fighting forced the Founders back to the drawing board. What came next? The Constitution.

Life and Society in the Colonial Carolinas

Explore the rise of plantation agriculture, slavery, class divisions, and the shaping of daily life in the colonial South—particularly in North Carolina and South Carolina.

Further Reading

Stay curious!