The First Amendment: America’s Blueprint for Freedom

The First Amendment protects freedoms of speech, religion, press, assembly, and petition.

The Dive

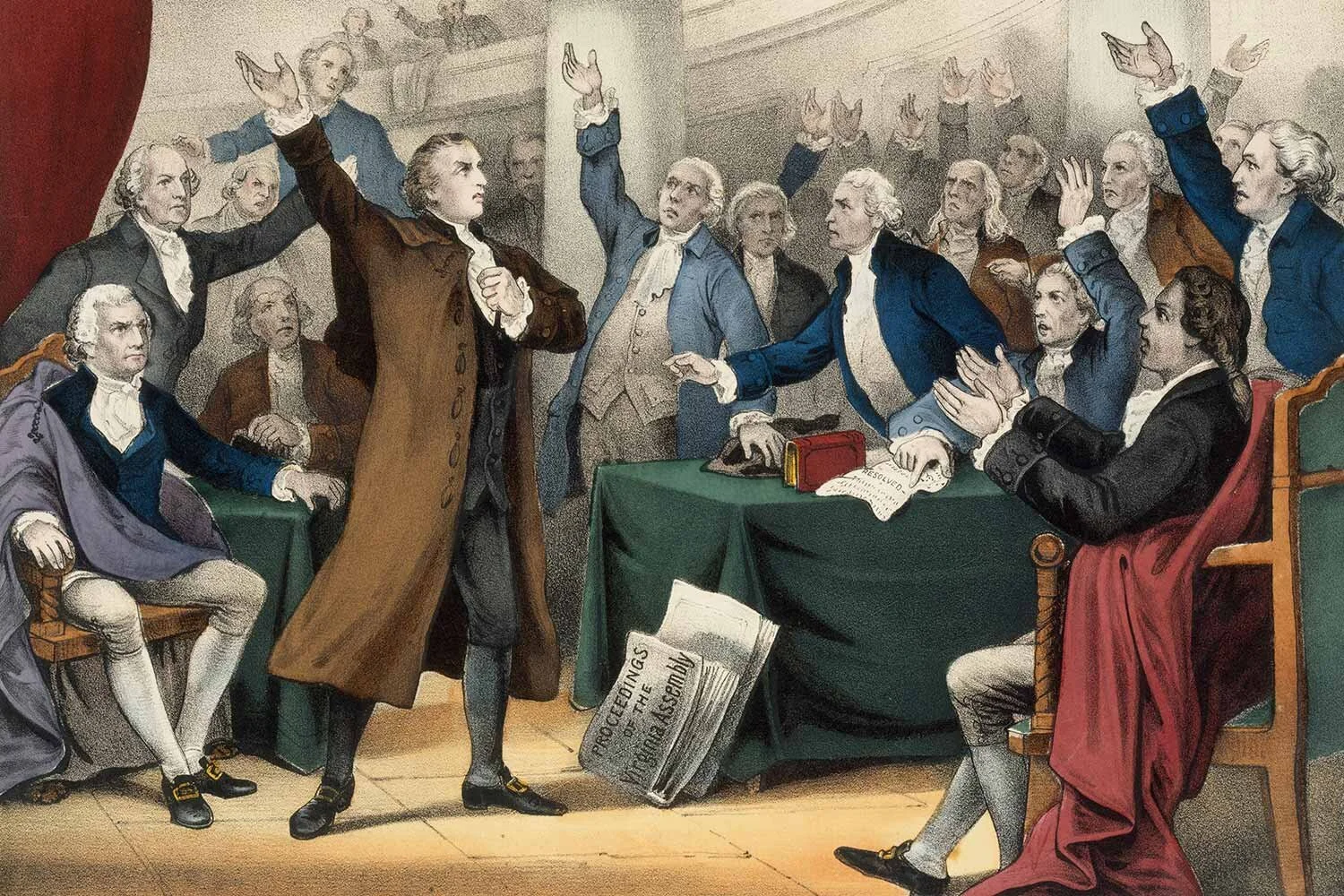

The First Amendment was not part of the original Constitution. In fact, the Constitution nearly failed to be ratified because many citizens demanded explicit protections for personal liberties. Out of that pressure, James Madison drafted the Bill of Rights, adopted in 1791, with the First Amendment leading the way. It enshrined five core freedoms—religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition—each designed to guard against the government silencing its people.

Religious liberty was a cornerstone. Colonists had seen what it meant to live under a state church that punished dissenters, so they wrote both the Establishment Clause (no national religion) and the Free Exercise Clause (freedom to practice faith). The tension between these clauses has produced landmark cases, from school prayer bans to debates about public funding for religious schools, that show how complex balancing freedom and neutrality can be.

Freedom of speech is perhaps the most famous clause, and for good reason. It allows citizens to criticize their leaders, challenge ideas, and share unpopular opinions without fear of government retribution. Over time, the courts have ruled that this freedom also covers symbolic expression. That's why, in cases like Texas v. Johnson (1989), even burning the American flag was upheld as protected speech. At the same time, the Court has made clear that not all speech is protected: incitement to violence, true threats, and obscenity fall outside its shield. From Schenck to Brandenburg to Tinker, the boundaries of expression have continually adapted to new crises and new generations.

The freedom of the press extends speech into print and media, recognizing that a democracy requires watchdogs. From colonial printers like John Peter Zenger challenging royal authority in 1735, to modern journalists reporting on government secrets, the press ensures that citizens are informed and leaders are accountable. Prior restraint (government censorship before publication) has been treated with deep suspicion by the courts, which have generally struck it down.

The right to peaceably assemble and petition gives freedom its muscle in public life. Citizens can gather, march, and demand change—from abolitionist meetings to civil rights marches to climate strikes today. Petitioning means citizens have a protected pathway to take grievances directly to the government. These rights remind us that democracy is not just about casting ballots; it is also about speaking collectively in public spaces.

The Supreme Court has constantly interpreted and reinterpreted the First Amendment, sometimes expanding and sometimes limiting its scope. For example, flag burning has been upheld as symbolic speech, while schools may restrict vulgar speech at assemblies. This evolving body of law shows how the meaning of freedom is not frozen in 1791 but lives through our institutions and debates.

Ultimately, the First Amendment is about trust: that ordinary people, not the government, should decide which ideas rise and fall. That trust is both radical and fragile. It requires citizens to tolerate offensive speech, a noisy press, and messy protests in order to preserve the deeper principle, that power in America begins with the people’s voice.

Why It Matters

The First Amendment is the backbone of American democracy because it secures the freedoms that make self-government possible. Without the right to speak freely, citizens could not criticize leaders, expose corruption, or debate solutions to public problems. Without a free press, we would lose the watchdogs who inform the public and hold power accountable. Without freedom of religion, diversity of belief and conscience would be stifled by state power. Without the right to assemble and petition, people would have no peaceful path to demand change. These rights work together to protect the most radical idea of all—that power belongs to the people, not the government. Learning how the First Amendment works, and where its limits lie, helps us understand both the power and the responsibility of free expression. It reminds us that democracy is not quiet or comfortable, but loud, contested, and alive. It is the clash of voices, the persistence of protest, and the courage to speak truth to power that keeps American freedom resilient in every generation.

?

Why did some states refuse to ratify the Constitution without a Bill of Rights?

How do the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses sometimes conflict with each other?

What kinds of speech are not protected under the First Amendment, and why?

Why is freedom of the press considered essential to democracy?

How have protests and assemblies shaped major social movements in U.S. history?

Dig Deeper

An introduction to the origins and importance of the First Amendment, connecting the Founders’ ideals to modern interpretations of freedom.

An introduction to the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition—and why they matter.

Explores the scope and limits of free speech protections, from political debate to controversial cases.

Explains the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses and how courts interpret the relationship between church and state.

Examines the press’s role in holding government accountable and the challenges of balancing security with transparency.

Related

The Bill of Rights: What Is It and What Does It Actually Do?

The Bill of Rights wasn’t added to the Constitution because everything was going great, it was added because the people didn’t trust the government. And they had every reason not to.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: The Battle That Built the Constitution

One side feared chaos. The other feared tyranny. Together, they gave us the Constitution—and the Bill of Rights.

Building a New Nation: Foundations of State and National Government

From the shaky Articles of Confederation to the Constitution and Bill of Rights, discover how America’s founders navigated the turbulent waters of self-government—and why North Carolina took its time joining the party.

Further Reading

Stay curious!