Reconstruction: Rebuilding a Nation and Redefining Freedom

The Reconstruction era was America’s attempt to stitch the nation back together after the Civil War while also transforming the meaning of freedom.

The Dive

When the Civil War ended, the United States faced a question far bigger than repairing broken buildings or burned farms. The real challenge was rebuilding a nation that had been torn apart over slavery and deciding what freedom, citizenship, and equality would actually mean going forward. For formerly enslaved people, especially in the South and in states like North Carolina, the end of the war brought hope, opportunity, and also fierce resistance. The era known as Reconstruction (1865–1877) became one of the most important and contested chapters in American history.

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. While this moment is often taught as the end of the Civil War, fighting continued in several places—including North Carolina—before the conflict officially ended. In April 1865, Union forces captured Raleigh, and Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered nearly 90,000 troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. This was the largest surrender of the war.

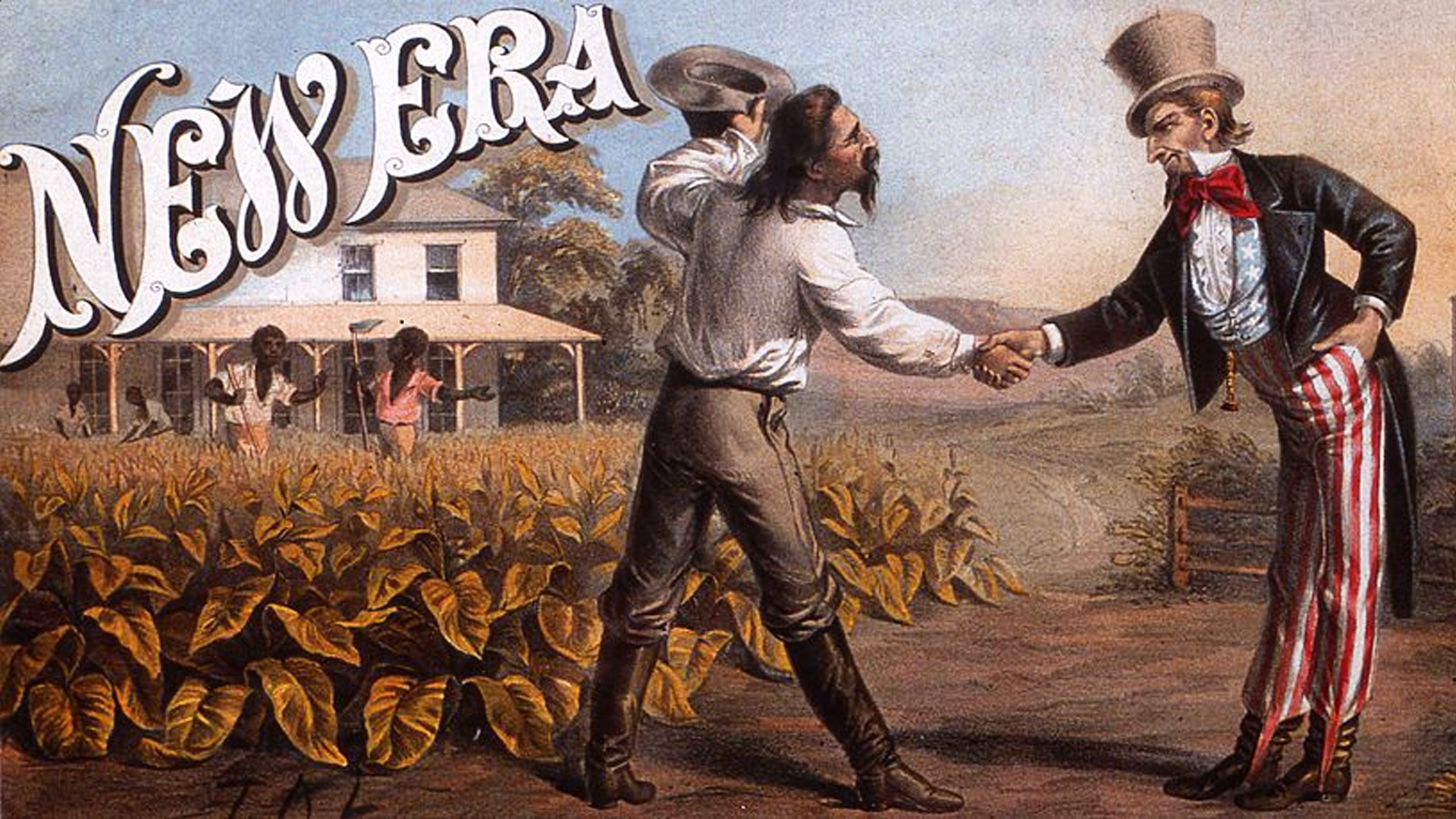

By August 1866, President Andrew Johnson finally declared the rebellion over. But peace did not mean justice. The nation now had to decide how to reunite the states and how to treat nearly four million newly freed people.

Reconstruction was not just about rebuilding the South—it was about redefining democracy itself. For the first time, the federal government stepped in to protect individual rights on a large scale. This effort reshaped the Constitution through three powerful amendments.

The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, ended slavery in the United States. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, defined citizenship and promised “equal protection of the laws,” meaning states could not deny basic rights to citizens. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, made it illegal to deny the right to vote based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Together, these amendments offered African Americans legal freedom, citizenship, and political voice. On paper, they represented some of the most democratic changes in U.S. history. In reality, enforcing them proved much harder.

To help formerly enslaved people transition from slavery to freedom, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865. Its work was especially important in Southern states like North Carolina, where slavery had shaped nearly every part of society.

In North Carolina, the Bureau helped negotiate labor contracts between Black workers and white landowners, offered legal support, distributed food and clothing, and—most importantly—helped establish schools. Education was seen as a key to freedom. One lasting result was the founding of Shaw University in Raleigh, one of the first historically Black universities in the South. For many freedpeople, education represented dignity, independence, and a future their parents had been denied.

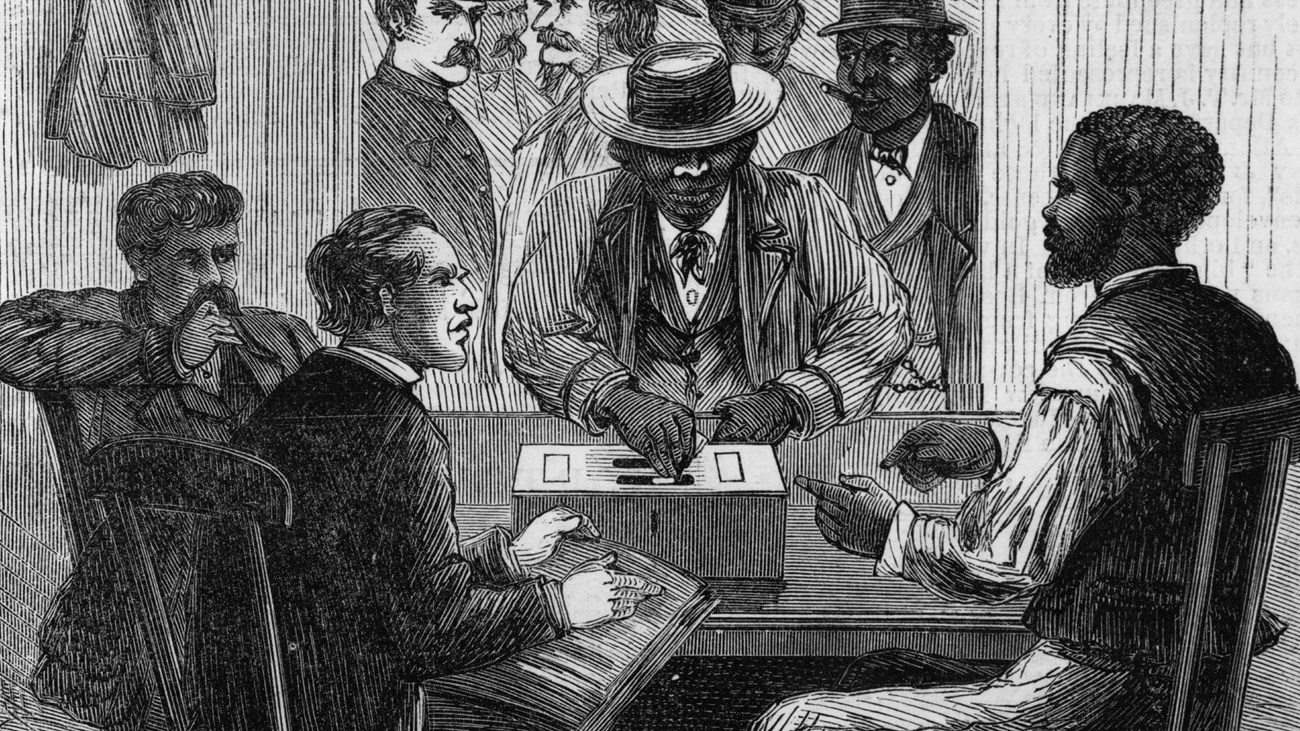

For a short but meaningful time, Reconstruction opened the door to Black political participation. African American men voted, served on juries, and held public office. North Carolina sent Black representatives to its state legislature, helping write new laws and constitutions.

Nationally, leaders like Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce served in the U.S. Senate. Across the South, more than 600 Black men served in state legislatures. These moments showed what a more inclusive democracy could look like.

Not everyone accepted these changes. Many white Southerners fiercely resisted Reconstruction. States passed Black Codes, laws designed to limit Black freedom and force African Americans into unfair labor systems that resembled slavery.

White supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan used terror to intimidate Black voters and silence their allies. In response, Congress passed enforcement laws that allowed federal troops to intervene. For a time, this reduced violence—but the commitment did not last.

Political movements known as “Redeemers” worked to restore white control of Southern governments. Over time, they succeeded by weakening federal protections and regaining political power.

In 1877, the federal government withdrew its troops from the South as part of the Compromise of 1877. Reconstruction ended. Without federal enforcement, many Southern states—including North Carolina—passed laws that limited voting rights and enforced racial segregation.

Although Reconstruction failed to fully protect African American rights in the long term, it was not meaningless. It proved that the Constitution could be used to expand democracy—and it exposed how fragile rights can be without enforcement.

Reconstruction raised essential questions that still matter today: Who counts as a citizen? Who deserves protection under the law? And what happens when a nation promises equality but fails to defend it?

In North Carolina and across the country, Reconstruction offered a glimpse of a more just democracy—and a warning. Progress is possible, but backlash is real. Laws alone are not enough. Rights must be protected, enforced, and defended by people willing to stand up for them.

Reconstruction reminds us that democracy is not finished. It is something each generation must choose to rebuild.

Why It Matters

Reconstruction was America’s first major attempt at building a multiracial democracy. It showed that sweeping change is possible when law, policy, and activism align—but also that rights can be rolled back if they aren’t protected. Its victories and failures still shape our debates over citizenship, voting rights, and equality today.

?

What major challenge did the United States face after the Civil War ended?

How did the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments change the Constitution?

What role did the Freedmen’s Bureau play in education and economic opportunity?

Why did Reconstruction face such strong opposition, and how was it expressed?

What lessons can we learn from Reconstruction about making rights real and lasting?

In what ways do the challenges of Reconstruction echo in today’s struggles for equality?

Dig Deeper

After the Civil War, Reconstruction aimed to reconcile the country and integrate freedpeople into society—but political conflict and resistance undermined many of its goals.

Related

The Emancipation Proclamation & The 13th Amendment

Freedom on paper is one thing; freedom in practice is another. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were giant leaps toward liberty—yet the road ahead for formerly enslaved people was long and uneven.

The Tulsa Race Massacre: Black Wall Street Burned

Greenwood was known as Black Wall Street—until a white mob burned it to the ground. The Tulsa Race Massacre wasn’t a riot. It was a coordinated attack. And it was nearly erased from history.

Jim Crow and Plessy v. Ferguson

After Reconstruction, the South built a legal system to enforce racial segregation and strip African Americans of political power. The Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 made 'separate but equal' the law of the land—cementing injustice for decades.

Further Reading

Stay curious!