Boss Tweed Is Brought Back to New York

Political cartoon-style image of Boss Tweed in a suit, symbolizing political corruption in New York City.

What Happened?

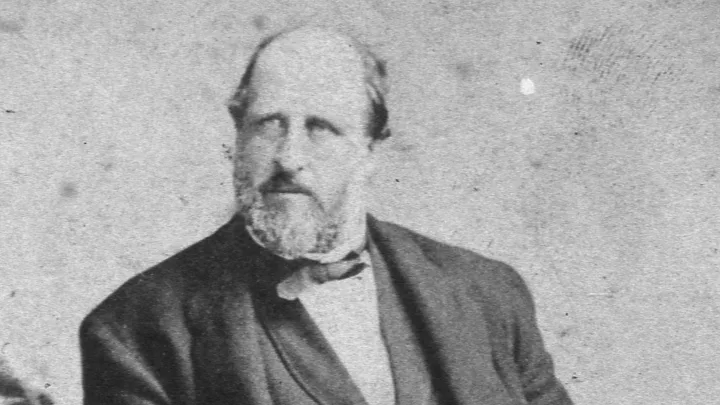

In the mid-1800s, New York City was exploding with growth. Immigrants poured into crowded neighborhoods, new buildings went up quickly, and city government had to keep up with demands for streets, schools, and services. Into this chaos stepped William Magear Tweed, known as Boss Tweed, who rose to power through Tammany Hall, the city’s Democratic political machine. A political machine was a powerful organization that helped people get jobs and services—but expected loyalty, votes, and favors in return.

Tweed was big in every way: his physical size, his personality, and his appetite for power and money. By the late 1860s, he led the so-called Tweed Ring, a group of politicians and businessmen who controlled contracts, city jobs, and elections. They used bribery, fake votes, and secret deals to stay in charge. In return, Tweed and his friends siphoned off enormous sums of money from city projects. Modern historians estimate that they may have stolen somewhere between 30 and 200 million dollars—an amount that would be worth many, many times more today.

The most famous example of their corruption was the construction of the New York County Courthouse, later nicknamed the Tweed Courthouse. On paper, it was supposed to be a normal civic building. In reality, it became a giant money vacuum. Contractors were paid outrageous amounts for simple work—like a carpenter receiving huge payments for very little woodwork, or a plasterer earning a fortune for just a few days on the job. Tweed even made money from a quarry that supplied the building’s marble. By the time it was done, the courthouse had cost more than some entire U.S. territories.

For a while, Tweed seemed untouchable. He appeared generous in public, donating to charities, funding orphanages and hospitals, and helping immigrants find food, coal, and jobs. Many poor families saw him as a protector when no one else cared about them. That is part of what makes his story so complicated: he did real good for some people while at the same time robbing the city on a massive scale. His kindness came with a price tag—political loyalty—and it helped cover up the scale of his crimes.

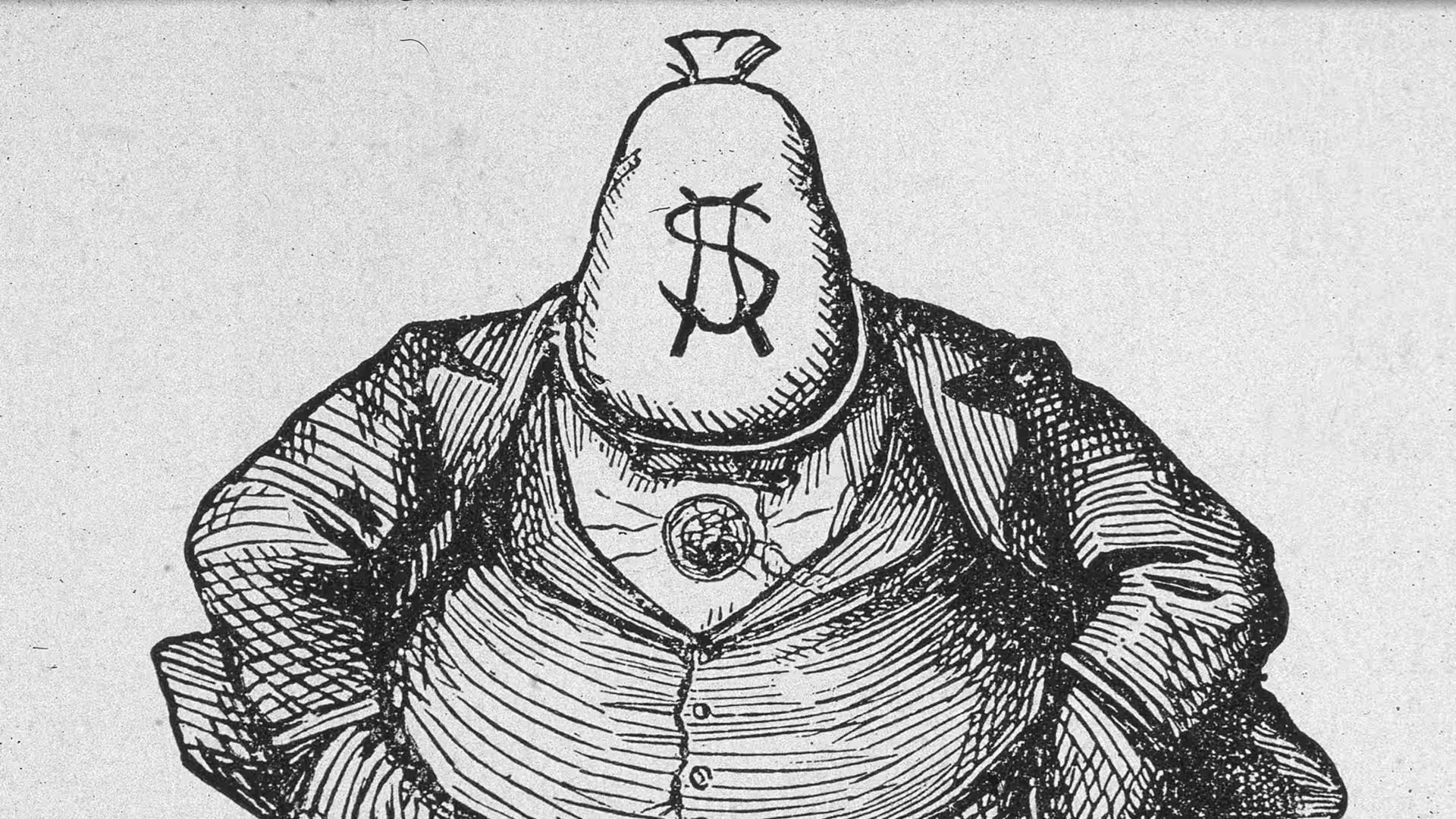

The turning point came when insiders in city government leaked detailed financial records to the New York Times in 1871. These documents showed exactly how badly Tweed and his ring were overcharging the city. At the same time, political cartoonist Thomas Nast attacked Tweed week after week in Harper’s Weekly. Nast’s drawings showed Tweed as a bloated, greedy boss surrounded by bags of money and a ferocious Tammany tiger. Many New Yorkers could not read, but they could understand Nast’s cartoons—and they were furious.

Public outrage grew, and reformers finally pushed back. Voters turned against Tammany Hall in the elections of 1871, and Tweed and many of his allies were removed from power. Soon after, Tweed was arrested and put on trial. It took two trials, but he was eventually convicted of crimes including forgery and larceny. He was sent to prison and ordered to repay some of the money he had stolen. Even then, he used his connections to get part of his sentence reduced.

In 1875, Tweed escaped from custody, fled New York, and made his way to Cuba and then to Spain. He tried to disguise himself, but the world had already seen his face—thanks to Thomas Nast’s cartoons. According to popular accounts, Spanish police recognized him from those drawings, arrested him, and handed him over to American authorities. On November 23, 1876, he was delivered back to New York City and locked up once again.

Back in prison, Tweed tried to bargain for freedom by confessing and naming names, hoping that cooperation would win him a pardon. It didn't. Most people had lost patience with him, and his reputation was ruined. He died in prison in 1878, largely abandoned by the wealthy allies who had once happily shared in his schemes. The Tweed Courthouse remained as a stone reminder of just how far corruption had gone in New York City.

Boss Tweed became a symbol of everything people disliked about machine politics: backroom deals, stolen tax money, and leaders who cared more about profit than honesty. But his downfall also showed the power of watchdogs in a democracy—journalists who dig for the truth, artists who communicate complex ideas through images, and ordinary citizens who refuse to look the other way. His story challenges us to ask hard questions: Who benefits from power? Who pays the price? And what can we do when our leaders are not serving the public good?

Why It Matters

Boss Tweed’s rise and fall show how dangerous it can be when one person and their friends gain too much control over government money and decision-making. His story reminds us that democracy depends on transparency, honest record-keeping, and people who are willing to speak out when something feels wrong. At the same time, it reveals how corruption can hide behind charity and helpful services, especially in communities that feel ignored. Learning about Tweed and Tammany Hall helps students see why strong institutions, investigative journalism, and active, informed citizens are essential for keeping public power in check.

?

How did Boss Tweed use both helpful services and corruption to gain and keep power in New York City?

Why were Thomas Nast’s political cartoons so effective in turning public opinion against Tweed?

What does the Tweed Courthouse tell us about how public projects can be abused for private gain?

In what ways did political machines like Tammany Hall both help and harm immigrant communities?

What modern tools (like investigative journalism, audits, or public records) help us catch corruption today, and how do they compare to the tools used in Tweed’s time?

Dig Deeper

An overview of how Tammany Hall shaped New York City politics and became a symbol of machine power and corruption.

A closer look at Boss Tweed, the Tweed Ring, and how political machines operated in 19th-century New York.

Related

Gerrymandering: When Maps Become Weapons

What happens when politicians choose their voters instead of the other way around? Welcome to the twisted world of gerrymandering.

The Gilded Age: Glitter, Growth, and the Cost of Progress

A glittering era of innovation and industry, the Gilded Age promised progress but delivered inequality. In the South, leaders dreamed of a 'New South,' yet industrialization offered opportunity for some while reinforcing systems of poverty and discrimination for others.

The Progressive Era: Reform, Regulation, and the Limits of Change

From breaking up monopolies to marching for women’s votes, the Progressive Era sought to fix America’s problems — but often left some voices out of the conversation.

Further Reading

Stay curious!