African American Gain the Right to Vote

On January 8, 1867, Congress granted African American men the right to vote in Washington, D.C.

What Happened?

The end of the Civil War left the United States struggling to redefine democracy after slavery. Millions of formerly enslaved people were now free, but freedom did not automatically mean political power. In Washington, D.C., African American men lived in the nation’s capital, paid taxes, worked government jobs, and served in the Union Army, yet they were still excluded from voting and decision-making.

On January 8, 1867, Congress passed the District of Columbia Suffrage Bill, granting African American men the right to vote in local elections. President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill, arguing that the federal government should not force racial equality and that voting rights should be controlled by white citizens and former Confederate states.

Congress overrode Johnson’s veto, marking a rare and powerful assertion of legislative authority over the presidency. This action reflected the growing influence of Radical Republicans, who believed Reconstruction required strong federal action to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people and prevent Southern states from restoring white supremacy.

The law made Black men in Washington, D.C. among the first African Americans in the United States to gain voting rights. This occurred three years before the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed voting rights nationwide, showing that progress during Reconstruction often happened unevenly and faced constant resistance.

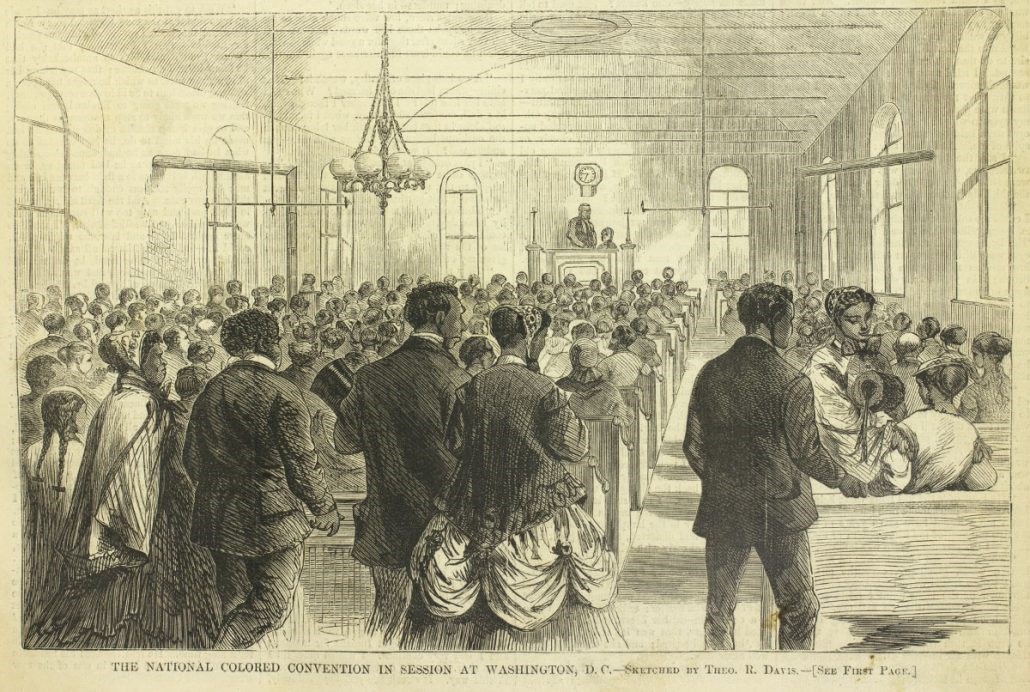

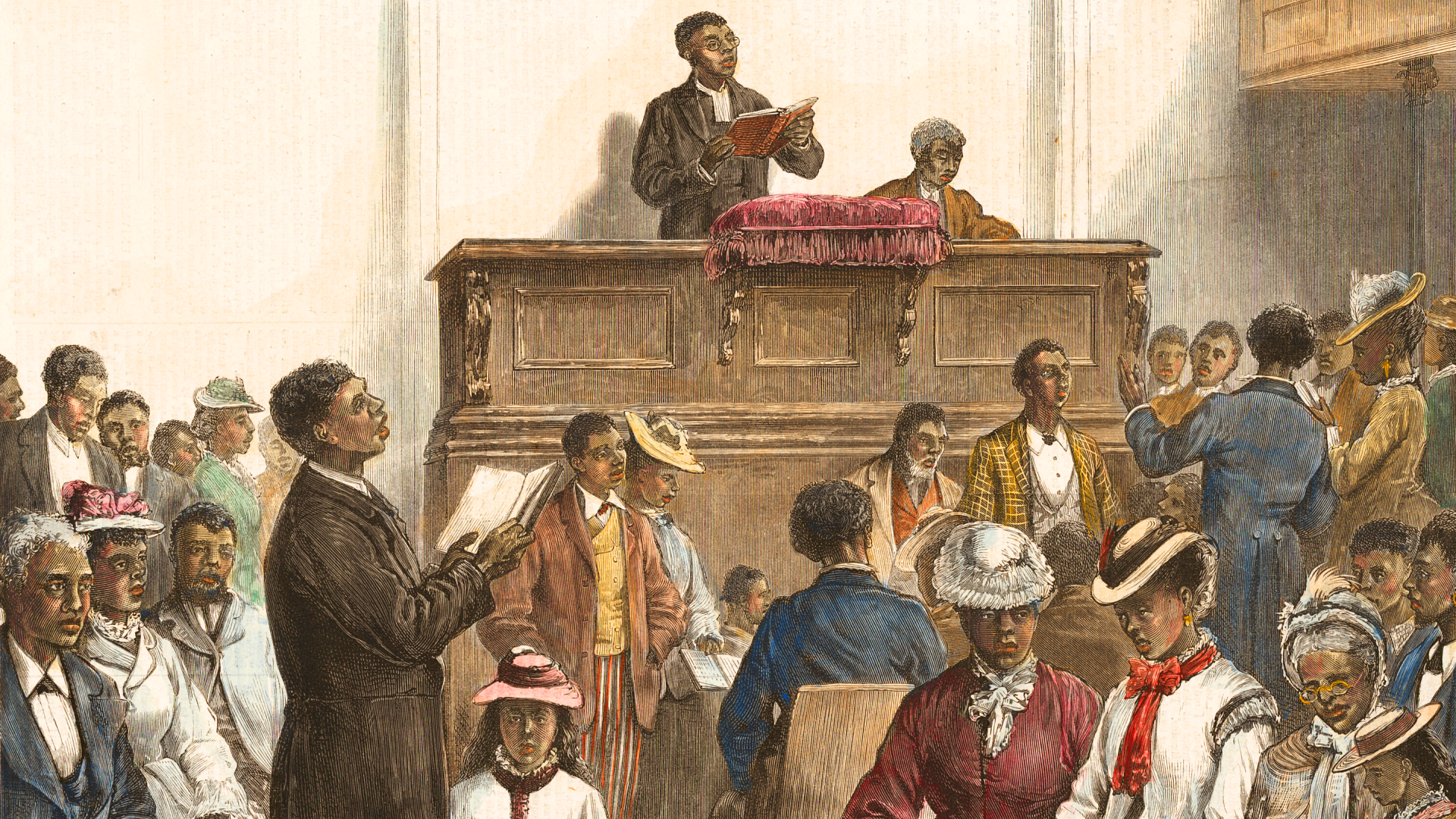

African American communities in the District responded with determination and excitement. Large numbers registered to vote, understanding that political participation was essential for protecting their safety, advancing education, and securing fair treatment under the law after centuries of exclusion.

Despite this milestone, voting rights in Washington, D.C. remained limited. Residents still lacked representation in Congress and could not vote for president until 1961. The city’s ongoing struggle highlights a central lesson of Reconstruction: expanding democracy requires not only laws, but lasting commitment to equality and representation.

Why It Matters

The decision to grant African American men the right to vote in Washington, D.C. showed that democracy does not expand on its own. It requires courage, conflict, and deliberate action. Even after slavery ended, many leaders resisted giving Black citizens political power, revealing how deeply inequality was built into the nation’s systems. This moment highlights both progress and limits: voting rights were extended, but only in one place and only temporarily. It reminds us that rights can be won, weakened, or taken away, and that protecting democracy requires constant effort, accountability, and public participation.

?

Why did President Andrew Johnson oppose giving Black men the right to vote?

How did Congress have the power to override the president’s veto?

Why was voting in Washington, D.C. different from voting in states?

How did this decision connect to the later Fifteenth Amendment?

Why do debates over voting rights continue today?

Dig Deeper

A short explanation of how the Fifteenth Amendment expanded voting rights after the Civil War.

Related

The Emancipation Proclamation & The 13th Amendment

Freedom on paper is one thing; freedom in practice is another. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment were giant leaps toward liberty—yet the road ahead for formerly enslaved people was long and uneven.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Enforcing the 15th Amendment

How a landmark law transformed voting access in the South and gave real force to the promises of the 15th Amendment.

Reconstruction: Rebuilding a Nation and Redefining Freedom

After the Civil War, the United States faced the enormous task of reintegrating the South, securing rights for freedpeople, and redefining citizenship and equality. Reconstruction (1865–1877) was a bold experiment in democracy—filled with groundbreaking laws, historic firsts, and fierce backlash.

Further Reading

Stay curious!